15 Pro Day Performances That Caught My Eye. Also, Why I Don't Use RAS

I went through a database of pro day results to find great workouts from players who didn't test at the combine. But I didn't use Relative Athletic Score, and I explain why.

March Madness is nearly over, which much more importantly means that the college football pro day circuit is nearly complete. Pro days are useful for NFL teams for a variety of reasons, but the most present and accessible information available to fans outside of the process are the workout scores players put together.

The sample of player workouts expands from several hundred during the NFL Combine to over 2000 over the month of March. Most of the players who weren’t good enough to earn a combine invite aren’t athletic enough to move the needle, so most of the results are unimpressive.

The average time of the 40-yard dash for receivers at this year’s NFL Combine was 4.46 seconds. In this year’s pro days, it was 4.64 seconds. But, some players stand out and eventually earn their way into the draft.

Last year, arguably the best defensive rookie in the draft – Kobie Turner – wasn’t invited to the NFL Combine. Nevertheless, after a strong performance at his pro day, the Los Angeles Rams drafted him in the third round. As a rookie, he put up nine sacks and eight tackles for loss, along with 16 quarterback hits.

I went through pro day results this year to see if there were any draft prospects that might have also flown under the radar. But importantly, I didn’t look for prospects with the best 40-yard dash times or the best composite athletic score.

Why I’m Not Using Relative Athletic Score

There are, of course, a number of tools that can make finding super-athletes a lot easier than ten years ago. The most prominent version featured online comes from Kent Lee Platte, @Mathbomb on Twitter, who has developed an easily digestible and marketable system called Relative Athletic Score.

RAS is an incredible tool that allows fans and analysts to very quickly understand the position-adjusted athletic capability of a player, which can be difficult with all the different sizes and weight across positions. In the 40-yard dash, 4.70 seconds is slow for a receiver, but blazing for a defensive tackle.

A change of 0.10 seconds is massive in the sprint, but much smaller in the three-cone. RAS condenses all of that into a way that avoids confusion. A 10.00 score for a receiver suggests the most athletic player ever at the position, which is also true for a 10.00 score at linebacker or tight end.

Unfortunately, there are a few issues with RAS when using it at a granular level. My decision not to use it here is less about issues with Platte’s approach or an argument that people should avoid it entirely and much more about going from big-picture to small-picture.

The first and most obvious issue to me is the non-positional aspect of the score. While it is true that every player is compared to every other player at the same position – see the 40-yard dash examples above – the workouts themselves are not indexed to what has historically mattered for each position.

The 40-yard dash may matter at cornerback, but it doesn’t much matter at defensive tackle. Nevertheless, both hold equal weight in a measure like RAS.

Another issue is that marginal differences in value run opposite the way one might expect. In terms of on-field performance and sheer athletic marvel, the difference between a 4.21-second 40-yard dash and a 4.25-second 40-yard dash is much larger than the difference between a 4.51-second 40-yard dash and a 4.55-second 40-yard dash.

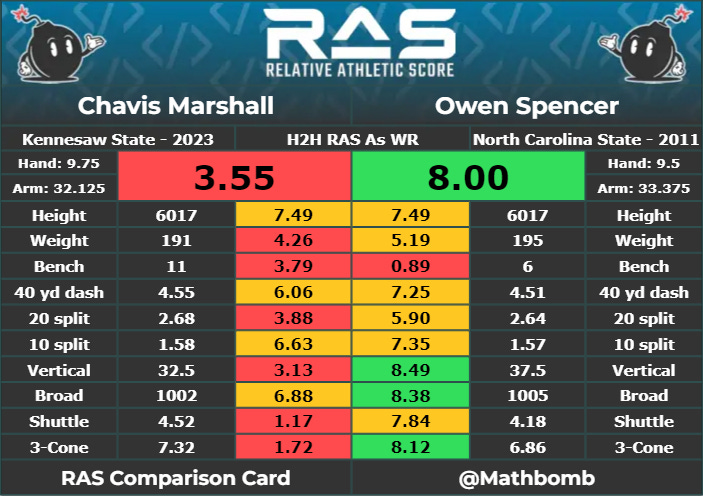

But in RAS, that difference is small at the fringes and large in the middle. Xavier Worthy has, appropriately, a 10.00 RAS score in the 40-yard dash with his 4.21-second score. A similarly-sized Courtney Moshood ran a 4.25-second 40-yard dash and earned a 9.98 score. When comparing Chavis Marshall and Owen Spencer, who have the same height and weight, we find that Marshall’s 4.55-second 40-yard dash merits a 6.06 RAS score while Spencer’s 4.51-second dash earned him a 7.25 RAS in the 40-yard dash.

These problems are magnified even more when it comes to scores that substantially outpace the competition. Byron Jones’ record-breaking 12’3” broad jump is seven inches (!!!) better than Keenan Isaac’s 11’8” broad jump, ranking first and second among cornerbacks in all-time performance in the drill. Their broad jump scores are both 10.00.

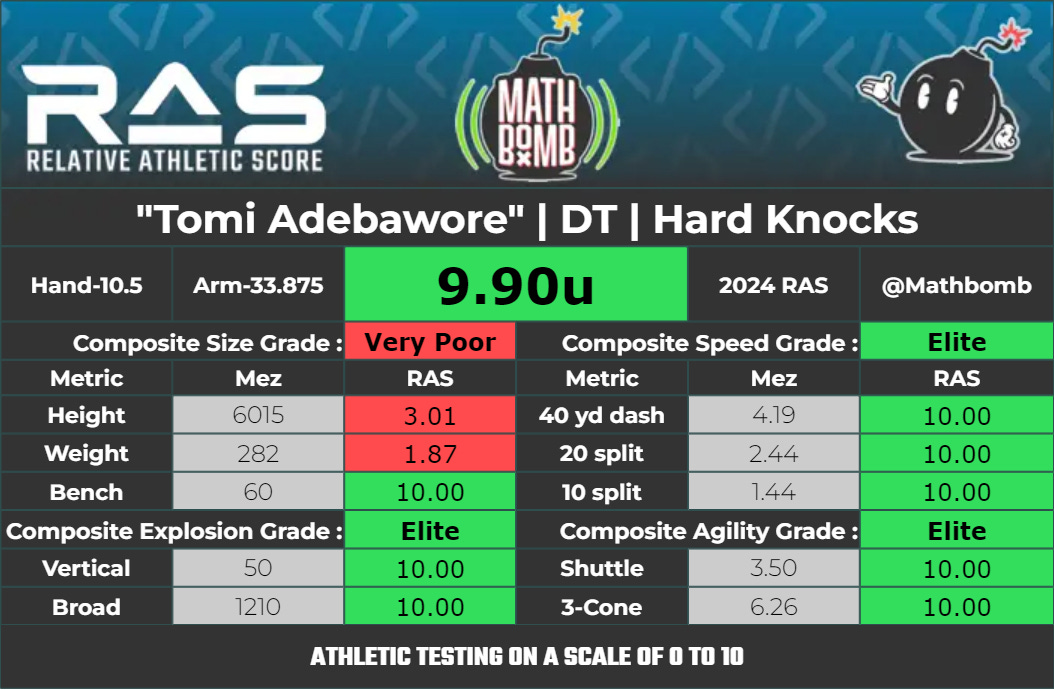

A third, minor, issue with RAS is that it seems to do a poor job handling positions with significant size differences. A good example of this comes when comparing Jordan Davis and Adetomiwa Adebawore. At their workouts, Davis weighed 59 pounds more than Adebawore, meaning that the fact that they played the same position wasn’t going to be all that helpful when comparing their workouts.

Adebawore posted arguably the best workout we’ve ever seen for a defensive tackle, running his 40-yard dash in 4.49 seconds, turning in a three-cone of 7.13 seconds and jumping 37.5 inches in the vertical leap while vaulting 10’5” in the broad jump. All of these scores are either the single-best score a defensive tackle has posted or in the 99th percentile. He earned a RAS of 9.72 because he performed his workouts at 282 pounds.

Meanwhile, Davis produced a workout just as outstanding at 341 pounds, running 4.78 seconds in the 40-yard dash, jumping 32 inches in the vertical leap and, somehow, landing just an inch behind Adebawore in the broad jump. Davis earned a score of 10.00.

Both are incredibly impressive scores, but Adebawore is unfairly capped. To take a closer look at this, we should note that we can broadly estimate how well a player will perform in any given drill, given their height, weight and NFL position. And, aside from the broad jump, Adebawore beat his size-adjusted workout expectations by just as much as Davis did. They should have near-identical scores.

But the nature of RAS is such that it is seemingly impossible for a player like Adebawore to earn a 10.00, regardless of how well he performs in various drills. A hypothetical player with his size that runs a 4.19-second 40-yard dash, runs a 6.26-second three-cone, jumps 50 inches in the vertical and beats Jones’ record at the broad jump would have a 10.00 in every workout category but only earn a 9.90 score in the RAS despite being the most athletic football player in human history.

Indexing these workouts to expectation would not only make more intuitive sense but would track with NFL performance a bit better.

The last issue with RAS is more one of personal preference than anything else. Most of these databases, whether it’s RAS or MockDraftable or something else, provide us with NFL Combine scores whenever possible, only supplementing with pro day workouts when necessary to fill in a missing workout.

Even though there’s a widespread perception that players perform better at pro days than the combine, these databases should still consider using pro day scores when they’re better.

Aside from the fact that it is tough to “accidentally” run fast, my own testing has found that “best available” scores tend to predict outcomes better than just using NFL Combine scores. This also ensures that prospects who feel like they might benefit from home cooking at a pro day are put on an even playing field with those who opt out of the combine or aren’t invited.

What Am I Using?

Over the past 15 years, I’ve maintained a database of workout scores from pro days and the NFL Combine and have tested them against NFL outcomes. These are tested both in raw form and in size-adjusted form – it turns out that the raw 40-yard dash matters at cornerback, but size-adjusted 40-yard dash matters at tight end.

The testing hasn’t been updated in the past several years, so while it might over-index for cornerbacks with length or trend towards other NFL fads from a few years ago, it still represents something a bit more precise than composite athletic scores. Nevertheless, for some comparison, I’ll use RAS scores to either point out when they align or don’t align with my own data.

I’ve also been able to control for role a little bit. There are two sets of athletic scores at defensive tackle – one for larger DTs, presumed to be nose tackles and one for smaller DTs, presumed to be three-techniques – three sets of tests for receivers that depend on height and separate tests at center, guard and tackle.

This way, we can avoid being impressed by athletes who specialize in skills that have little to do with their projected NFL job. RAS stars like Damiere Byrd and Dri Archer didn’t test well in position-specific scoring while average RAS athletes like Sidney Rice and Malcolm Jenkins are recognized for the high-level positional athletes they are.

Terence Steele had a high RAS but low position scoring while Cordy Glenn was the opposite.

Using that data, I’ve identified 13 players who either were not invited to the NFL Combine or didn’t perform key tests while there that might be worth keeping an eye on. There are also two players with unique scores that fascinated me enough to mention.

13 Players With Great Pro Day Testing

Tyler Harrell, WR Miami (FL)

A fifth-year player that never really broke out, Tyler Harrell had all the opportunity in the world to put up big numbers after transferring twice, first from Louisville to Alabama in 2022 and once again from Alabama to Miami in 2023. But he couldn’t break his career-high 523 yards from his 2021 season, so will have to hope he has a better NFL career than college career, like super-athletes Donovan Peoples-Jones and D.K. Metcalf.