Croke Park Disaster: History Haunts the Vikings, Rewards the Steelers

The Vikings lost to the Steelers 24-21. What does that have to do with the bloody history of Croke Park? Enough.

Outside of Croke Park, where the Vikings lost to the Steelers 24-21 on a last-second attempt to mount a comeback, there’s a memorial to 14 people killed by a mixed force of Royal Irish Constabulary, Auxiliary Police and British Military — among those dead were Irish Gaelic footballer Michael Hogan from Tipperary, for whom a stand at Croke Park is named in his honor.

This incident is known as Bloody Sunday, a moniker which has since been applied to equally weighty historical events like the much more famous Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland in 1972, violent police action against civil rights activists in Selma in 1965, and the violent breakup of a steelworkers strike in 1923 in Newfoundland. The name has also been applied to more mundane affairs, like a particularly injury-riddled NFL game. It even gives its name to several podcasts and at least one book covering the sport.

Nominative trivialization is not new, nor is it particularly condemnable. Over time, history becomes a backdrop more than a somber reminder of what has produced our current social conditions.

After all, it is perhaps with some irony that the Irish welcome the Vikings to the island after the atrocities committed by plunderers of the same name centuries ago — raiders who later became part of the island’s history and ethnography.

Nevertheless, the Irish record of resistance to imperialism runs through the island and in some ways defines Dublin. Though Irish independence was, relatively speaking, late-won, Ireland has long been proud of their tradition of asserting self-determination in the face of oppression.

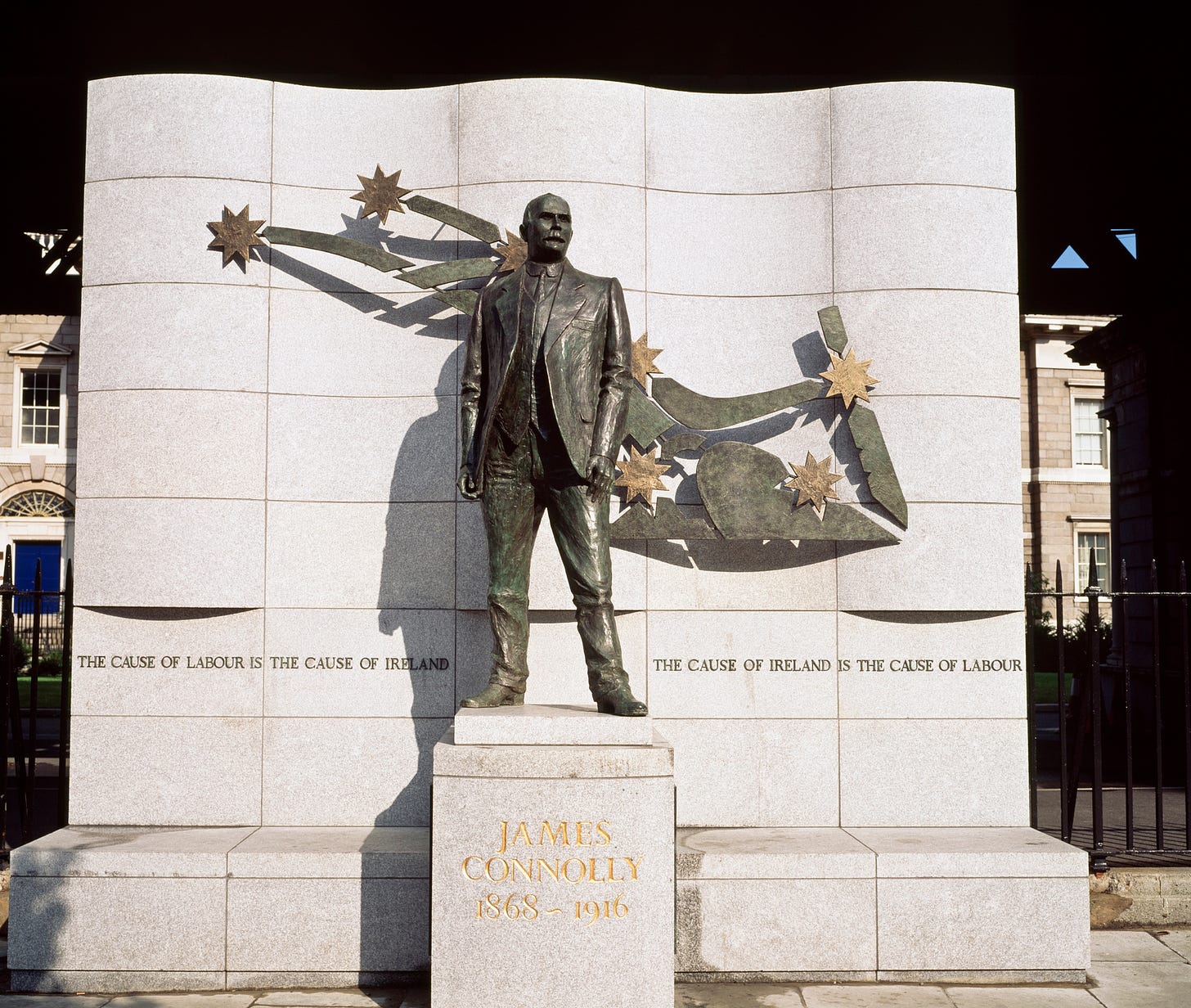

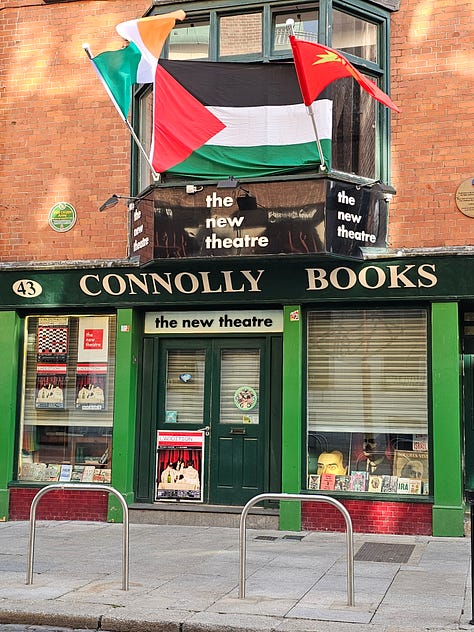

In the city center, one can find not one, but two monuments to James Connolly, a socialist Irish patriot, executed four years prior to Bloody Sunday for his role in the 1916 Easter Rising.

It is indelible and closely tied to American history. Connolly was loved in places beyond Ireland; he had visited the United States with other Irish labor leaders and helped win hard-fought battles for the labor movement across the United States. Mother Jones, an Irish immigrant whose name now recalls a digital publication more than labor progress, traveled with Connolly and helped found the Industrial Workers of the World — she was, at the time, known as “America’s Most Dangerous Woman.”

She, along with Connolly and other Irish and Irish-American labor leaders like Elizabeth Flynn Rodgers and Terence V. Powderly of the Knights of Labor; Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, a founder of the ACLU; Jim Larkin of the Socialist Party of America; and Patrick Quinlan of the IWW helped establish a framework for labor rights in the United States.

These weren’t small victories; they were enormous advances in labor protection and they included the formation of the Department of Labor, the eight-hour workday, weekends, the passage of the Clayton Antitrust Act, the establishment of uniform worker safety reforms following the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and an explosion of union membership — and collectively bargained contracts — in the 1900s and 1910s.

The history goes both ways, too. Irish men (and some women) fleeing the Great Famine from 1845 to 1852 enlisted on both sides of the conflict in the American Civil War and took that warfighting experience back with them to Ireland, becoming part of a movement called Fenianism — secret political organizations fighting for a free Ireland with the understanding that military revolution would be necessary.

Easter Rising

That brings us to the Easter Rising and Bloody Sunday. With the ability to train soldiers, Irish leaders returning from the United States, such as Connolly, as well as Irish leaders who stayed in Ireland, like Patrick Pearse of the Irish Volunteers, raised paramilitary forces and coordinated among themselves to force the British into recognizing independence — or at least Home Rule.

The movement’s capture of the General Post Office and other government buildings was the most significant uprising to that date for Irish independence since a rebellion more than a century prior. Despite British involvement in World War I — an involvement that also drained Ireland of its military resources — they deployed significant military assets to root out those who had fought in the Easter Rising.

The British response was a military crackdown. That meant criminalization of all nationalist activities — peaceful or otherwise — and executions of the leaders of the Easter Rising, including Pearse and Connolly. That approach spiked support for Irish independence and, in particular, a militaristic approach to achieving it. No longer were many Irish nationalists content to win their right to self-determination through negotiation and politics. The British made it clear that wasn’t going to work.

Thousands were arrested by the British in the aftermath of the Easter Rising, many held without trial in jails and prison camps throughout Wales and England. The few who were tried were tried without the ability to mount a legal defense, adjudicated in secret military tribunals.

This and other elements that characterized the brutal British retaliation inspired more support for Irish Republicans — here meaning those in support of a Republic of Ireland — leading to landslide electoral victories in the Irish parliament for independence parties, increased recruitment in paramilitary organizations and a formal declaration of independence in 1919.

The British response to this was even more repression, increased military presence on the island and martial law enforced formally by British forces, semi-formally with local police forces and informally with paramilitary forces supported by the British.

This was devastating, especially for smaller Irish locales in the country, many of whom found their economic cores literally burned out by members of the royal police forces, known as the Royal Irish Constabulary, or RIC. The Irish Republican counter-response was agitation and, often, military action — including assassination of spies and military agents.

Croke Park and Irish Independence

On November 21, 1920, at least 14 people were killed by Irish Republicans, most of them members of a British intelligence unit called the Cairo Gang. Reports vary on the total dead or wounded or how many civilians were involved — and whether informants count as civilians — but at least one civilian was wounded. British police and military forces descended on Croke Park hours later with orders to search members of the crowd.

This wasn’t random; Gaelic football and hurling had been growing in Ireland as part of a movement to revive Irish cultural identity. Attendance for both games had been growing sharply in response to British repression. Indeed, in 1902, the Gaelic Athletic Association banned any players from playing “imported” sports like soccer, hockey or cricket.

As journalist Michael Foley wrote in his book, The Bloodied Field: Croke Park, Sunday 21 November 1920, “The ban helped the GAA articulate things they could never publicly say themselves.” Part of this national movement meant investing in stadiums that could host ever-larger crowds. One of the first such major investments from the GAA was in Croke Park, where national-level tournaments among county teams drew record crowds.

So, when GAA leaders were arrested following the Easter Rising, it was no surprise. The British understood just as well as the Irish did the importance of Irish sport to their national character. It was also, therefore, not shocking to imagine the British and their loyalist supporters would anticipate something similar in a match in Croke Park four years later.

As they gathered to search members of the crowd, the RIC — also known as Black and Tans for colors on their uniform — were meant to provide some measure of crowd control and perform the bulk of the searches. They arrived to the stadium in waves, first assisting in searches and establishing a perimeter. But after a plane flying overhead dropped a flare, late-arriving constabulary forces would drive into the crowd, creating a panic that — in their minds — justified firing into the crowd.

Reportedly, the first to die were children. Propped up in trees to watch the game or along the stadium wall, they fell to fire from the RIC. Foley described the approach of one member of the Black and Tans, Roland Knight.

He watched the crowd scramble towards the wall behind the canal goal, and aimed his revolver at a knot of men. Fire. He turned to face the rest of the pitch. He picked a moving target and took aim. Fire. Again another. Aim. Fire.

Knight used a revolver. Others had machine guns mounted in armored vehicles. With RIC and auxiliary forces at every exit, there wasn’t a safe place for the crowd to flee. Seven members of the crowd died from gunshots at the site and five more died in the following days from their gunshot wounds. Two more died from the stampede of the crowd. One of those who died was Gaelic footballer Michael “Mick” Hogan. The wounded numbered in the dozens, with at least one count bringing it to 65.

Despite international outcry and the demands of Irish members of the British Parliament, no public inquiries were held. Instead, there were private inquiries sealed from any scrutiny. It wasn't until the year 2000, 80 years later, that they would be unsealed. Multiple officers in British employ would later testify that there was no provocation given for firing upon the crowd.

The blood-soaked grounds of Croke Park turned into a rallying cry and had set off a chain of response and counter-response that eventually led to a truce in July of 1921 and, later that year, Irish independence.

If one feels it’s a bit gauche to integrate politics into sports, one might want to take it up with the Gaelic Athletic Association. Or even the Irish who attended the 2025 game, joyfully belting out Zombie by the Cranberries, a song that recalls the Troubles — a related conflict over whether Northern Ireland should unite with the Republic of Ireland to bring the entire island under the political control of one government.

It’s the same old theme, since 1916

In your head, in your head, they’re still fightin’

With their tanks and their bombs and their bombs and their guns

In your head, in your head, they are dyin’

There were those who didn’t like that the song was playing at Croke Park, perhaps because of its reductive understanding of the conflict and Croke Park’s strong political history.

Of course, one need not be directly affected by political violence to be horrified and disgusted by the killing of innocent children, and O’Riordan’s lyrics were a visceral, human and understandable response to an act of brutal, murderous violence. It’s not a crime that her perspective on political violence in Northern Ireland was so simplistic that the lyrics to Zombie could have been scrawled with a crayon. But her belief that this violence was perpetrated solely by unthinking, unfeeling, brain-dead “zombies” was embarrassingly reductive, and wholly out of step with any serious study of the conflict.

Rooney Come Home

That the NFL chose the Steelers to host their first regular-season game in Ireland is no mistake. It is also, perhaps shockingly, wrapped up in its own politics.

The late Dan Rooney, who helped construct the Steelers dynasty of the 1970s as a member of the front office under owner and father Art Rooney, was appointed to be the ambassador to the Republic of Ireland in Barack Obama’s first term.

The Rooneys, like so many Irish Americans, travelled to North America in response to the Great Famine. They would move often and Art Rooney’s grandfather, also named Arthur, had even lived in Wales for a time.

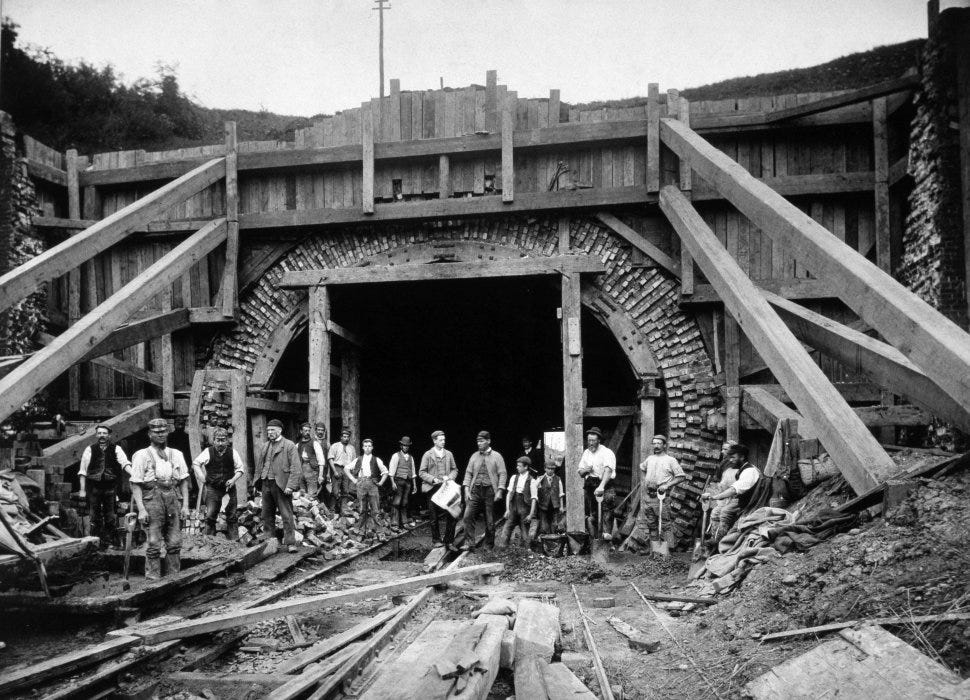

He became one of many “navvies” who helped with the construction of navigational canals throughout the island, either directly through engineering work or indirectly through supplementary work, like in the iron industry. That’s where Rooney found himself — a Steeler before the Steelers.

The Irish in particular worked much of the iron and steel industry in the United Kingdom and later constituted a significant part of the iron workforce in the United States. Indeed, It might feel appropriate that the Steelers and its fanbase have a claim to the labor history that set the stage for its eventual independence.

After all, one of the first, most frequent and final sites of agitation for Connolly was Pittsburgh and its steelworkers. It was his victory for Pressed Steel at McKees Rocks that set his heart back on the path to revolutionizing Ireland’s labor force.

Arthur Rooney’s son Dan — grandfather to the Dan Rooney who would become the ambassador to the Republic of Ireland — grew up in Pittsburgh after Arthur moved the family back to North America. The elder Dan Rooney would then raise Art Rooney, the Art who would purchase the rights to found a football team in the NFL for the city of Pittsburgh.

That team, like many NFL teams of the 1920s and 1930s, was named after the local baseball team, the Pittsburgh Pirates. After several years, they hosted a contest to rename the team, choosing the Steelers to reflect the city’s industry. An unusual series of events led to Rooney selling the team, buying the Eagles and then swapping ownership between the Eagles and Steelers to reacquire the Pittsburgh franchise, all in one offseason — officially an unbroken record of ownership, but not in reality.

The Rooney connection to Ireland never died, and the Rooneys would often make pilgrimages back to where their family had come from, though they had originated from Northern Ireland, now a separate political entity carved out by the 1921 treaty.

Dan Rooney is the only US ambassador to the Republic of Ireland to have visited all 32 counties on the island. He had thrown himself into philanthropic work throughout Ireland. The goodwill this has generated — and the Steelers’ insistent push to showcase NFL games in Ireland — has given them a unique homefield advantage.

The Rooneys have made sure the Steelers regularly visit the island to promote the game, play preseason games, host flag football tournaments and host watch parties. This has generated a strong Steelers fanbase — one that has blended in well with the sizable traveling contingent of American Steelers fans.

In the four games the Vikings had played abroad in the International Series, it would have been fair to estimate or even strongly argue that they had the larger fanbase of the two in the game. Not so in Ireland, where Steelers fans outnumbered Vikings fans in every corner of the city on every day of the week — outside of a select few, designated, Vikings pubs.

The marketing push of the Steelers — who have exclusive territorial marketing rights among NFL teams on the island — has exceeded the deep genealogical connection the historical Vikings have to the island. Raiders, settlers, then traders, the Scandinavian navigational explorers who occupied Dublin in the ninth century had intermingled with the local population by the turn of the millennium.

That integration was strong enough that when the High King of Ireland, Brian Boru, attempted to subjugate the King of Dublin, Sitric Silkbeard, the constructed mythology of an Irish versus Norse conflict had lost its meaning, as forces on both sides shared a Hibernian and Norse heritage.

Dublin north of the River Liffey is largely constructed on top of those Viking ruins; Norse loyalists were pushed to the north after the conquest by the Anglo-Normans, finding themselves back at the northern edge of their ancient battle lines against Brian Boru in Drumcondra. It is where Croke Park is today.

Two massacres — Brian Boru’s of the Vikings and the British of the Irish — marked the spot of a Bloody Sunday where the Vikings ultimately fell short.

The Vikings Failed to Recapture Dublin

Like with history, the Vikings’ first forays in Ireland were successful. Starting off the day with an impressive Jalen Redmond sack, the Vikings earned the ball back quickly and methodically marched down the field to set up a score, though a fumble scare — deftly avoided by Jordan Mason’s heady decision to reach out and contact the ball while out of bounds — nearly set up a defensive score, perhaps not quite in the way many had imagined after the Vikings’ impressive Week 3 performance.