Entering Mythical England, the Vikings Comeback Win Over the Browns Befit Their Folklorish Past

The Vikings beat the Browns, coming back from behind in London, at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium. The seeds of this victory were sown centuries ago; both leaned on their cultural heritage to close the day

Entering their fifth game in London, the Vikings hoped to maintain their prestigious undefeated record in the United Kingdom, having failed to make that an undefeated international record after losing in Dublin to the Steelers last week.

Despite some of their own best efforts, they succeeded, with backup (?) quarterback Carson Wentz engineering a fourth-quarter comeback and game-winning drive with only seconds left on the clock to put the Vikings up 21-17.

The Browns were the official home team, and the stadium engineers did their best to ensure that this meant a home atmosphere for the Browns, but the Vikings fanbase clearly outnumbered the Browns fanbase at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium.

England is often imagined by those in other Western countries as the home of folklore and fantasy. This is encouraged by the English themselves; the English flag bears the cross of St. George, who, in legend, slew a dragon.

Their veneration of King Arthur is no different and their celebration of myth and mythos has been a big part of their international marketing.

This history of legend should have provided the Browns with another source of Homefield advantage. But this legend is as fickle as the Browns quarterback depth chart.

The Browns and their Brownies

In English, Scottish, Manx and Welsh folklore, a brownie is a fae creature who provides a chosen home with essential services, primarily housecleaning and, in some cases, guardianship.

The brownie is also an official mascot for the Cleveland Browns.

Running throughout the folklore of the island, particularly in the north, brownies bear many names. Depending on the region and the language, they may also be called broonies, bwcas, fenodorees, brunaidh, bwabach, hobs/hobgoblins or gruagach.

Brownies of folklore would often leap into action after the inhabitants of the home they served would go to bed, cleaning and organizing behind the scenes, sometimes even milking cows and repairing crops. They might even defend the property from thieves or other fae folk.

The depth of their service, especially to favored family members, could run quite deep. As one tale told in the Katharine Briggs’ Encyclopedia of Faeries details:

There was a brownie who once haunted the old pool on the Nith, and worked for Maxwell, the Laird of Dalswinton. Of all human creatures he loved best the laird’s daughter, and she had a great friendship for him and told him all her secrets. When she fell in love, it was the brownie who helped her and presided over the details of her wedding.

He was the better pleased with it because the bridegroom came to live in his bride’s home. When the pains of motherhood first came to her, it was he who fetched the cannie wife [midwife]. The stableboy had been ordered to ride at once, but the Nith was in spate and the straightest path went through the Auld Pool, so he delayed.

The brownie flung on his mistress’s fur cloak, mounted the best horse, and rode across the roaring water. As they rode back, the cannie wife hesitated at the road they came.

‘Dinna ride by the Auld Pool,’ she said, ‘we mecht meet the brownie.’ [Translated: “Don’t ride through this pond, or we may encounter a brownie.”]

‘Hae nae fear, gudwife,’ said he, ‘ye’ve met a’ the brownies ye’re like to meet.’ [“Don’t worry about that, you’ve met all the brownies you’re likely to meet.”]

With that he plunged into the water and carried her safely over to the other side. Then he turned the horse into the stable, found the boy still pulling on his second boot and gave him a sound drubbing.

Brownies would be sensitive to the treatment of the stewards of the property; treat them poorly, and they turn from kind helpers into vengeful sprites. In return for their services, they would often only require small treats left out at night, such as a bowl of milk or porridge. The treats could not be explicitly demarcated to the brownies, of course — they merely needed to be left overnight within reach of a brownie.

These brownies didn’t quite look as polished as the Browns logo would suggest; though the description often depended on the storyteller, they were often haggard, three-foot-tall men, raggedly dressed in makeshift clothes with brown (often soot-stained) faces and shaggy heads.

One hoped to avoid offending them. That might mean complimenting then directly, insulting them (directly or otherwise), attempting to spy on them during their work, or, as readers of the Harry Potter series may have surmised from the similarities between brownies and the book’s house elves, providing clothing.

Indeed, the name Dobby takes direct inspiration from the name these faeries took in Yorkshire, Dobby (in other parts of Northumbria, the name they took on was often a derivation of this — Mr. Dobbs, Dobie, etc.).

When brownies were angered, they would often leave and take all the good luck they bestowed on a home with them. This could be more catastrophic than it sounds; stairs fall into disrepair, cows bear less milk, and crops wither unexpectedly.

In some legends, brownies could turn into another J.K. Rowling staple, a boggart. Unlike the Rowling creation, however, these boggarts wouldn’t malevolently turn into one’s fears but rather would play pranks, like hiding various foodstuffs or leaving out toys so that parents would blame children for not cleaning up. Rowling’s boggarts are more like the folklorish bogles or bogies.

In even worse circumstances, they turn into poltergeists, harassing the inhabitants and throwing objects around. These could cause serious injury or even death.

Every formulation was different. In some tales, they had no nostrils. In others, no mouth. Others still eliminated fingers from their hands, giving them one pad where their fingers would be and an opposing thumb, much like permanent mittens.

Some were clever, others fairly dim. They sometimes were solitary in nature, while others lived in packs or crowds.

Like most folkloric creatures, their tales have been reappropriated for use in different social contexts again and again. The first time we see brownies in literature comes in a series of children’s novels — perhaps the first children’s books in the English language — by a woman named Juliana Ewing, often stylized as Ms. Ewing in her books. The book’s title was The Brownies and Other Tales.

The function of a brownie in a household was re-established in this book, but the ultimate lesson meant to be learned from these stories was not that brownies were real, but that it was up to the children to perform these chores. The brownies were a rhetorical device in these books more than anything else.

This ethic of helpfulness in brownies, reestablished by Ewing, inspired Robert Baden-Powell and his sister Agnes Baden-Powell to name the junior level of the Girl Guides (later Girl Scouts) “Brownies.”

OK, But the Browns

How did the Browns end up with it?

We don’t exactly know.

The closest anyone has come to unearthing the truth of it is Browns historian and fan Barry Shuck.

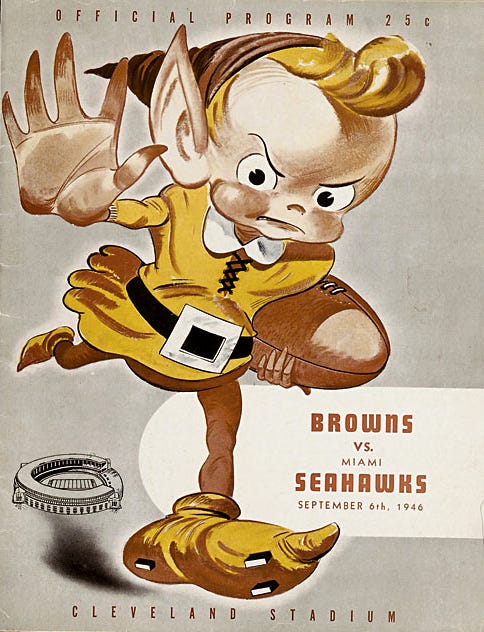

We know that the Browns are named as such because of their first coach, a godfather to modern football, Paul Brown. As an AAFC (All-American Football Conference) outfit, along with eventual NFL teams, the San Francisco 49ers and Baltimore Colts, they didn’t initially get the respect of the big leagues, critical in part because the Browns dominated the AAFC with three consecutive titles.

The league lacked neither talent nor money. But the talent and the stability of its respective team ownerships were not equally distributed. The league couldn’t turn a profit and merged three teams with the NFL.

The Browns immediately won in this new league, starting their inaugural 1950 season by demolishing the then-champion Philadelphia Eagles. After they won their championship game against the Los Angeles Rams, thousands of fans stormed the field, getting close enough to the players to tear off jerseys.

As the Cleveland Plain-Dealer reported in 1950:

The insanely happy fans who couldn’t get near the players went after the goalposts, and they tore them down in one gigantic surge. When last seen, the goalposts were being carted out of the stadium by a whole gang of souvenir-hunters.

Demonstrations were equally as riotous in the stands. A bonfire was built of wastepaper in the center field bleachers and city firemen, answering the alarm, reached the scene only to find that stadium ushers had extinguished the blaze.

Exciting stuff, but it doesn’t tell us much about brownies. Did they pick a brownie because it so naturally fits the moniker the team chose for itself? That seems likely, but we can’t know for sure. Especially because the name of the mascot is Brownie the Elf, not X the Brownie.

He’s an elf??

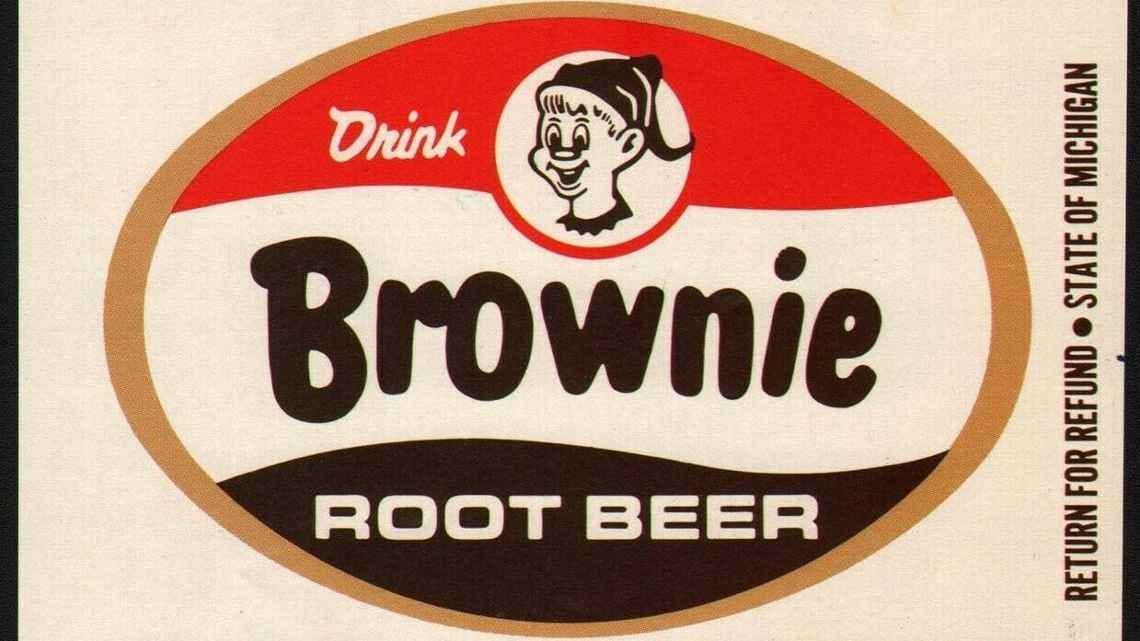

Steve King, a former Northeast Ohio sportswriter, told Jake Trotter at ESPN that it may be a product of a root beer advertisement painted on a building in Massillon, Ohio — where Paul Brown originally coached his legendary high school team, the Massillon Tigers.

In either instance, the connection to the folklorish brownies — elf or not — was not lost on the Browns, who commissioned artwork to adopt the mascot. Whether they did so by modeling the root beer is wholly unknown.

At various times, the NFL seemingly disapproved of this impish connection. The Browns once employed a little person, Tommy Flynn, as sideline entertainment. He would shag passes during pregame warmups and mimic Paul Brown on the sidelines, often pantomiming his genuine acts of coaching with exaggerated movements to rile up the crowd.

The NFL told the Browns to cut it out — not because they were in any way sensitive to these kinds of portrayals of those with dwarfism, but rather because they thought the spectacle was more befitting of a minor league baseball game or college football game. Seeking credibility as a professional outfit, they wanted a more serious atmosphere in their games.

There is some sense that this also motivated a de-emphasis on the Brownie mascot. In either case, the purchase of the team by Art Modell killed the concept. As he told newspapers in 1961, “My first official act as owner of the Browns will be to get rid of that little fucker,” referencing the elf/brownie.

Modell did not turn out to be a particularly loved owner for Browns fans. A well-publicized dispute between the namesake coach and the new owner didn’t help things; Modell promised Brown independence, but would meddle in team affairs and criticize Brown’s playcalling in the owner’s suite — criticisms that would trickle down to Brown himself, which further deepened the divide.

Though Modell doesn’t earn much in the way of historical leniency in Cleveland, it should be noted that players chafed under Brown at this point in time, with others among them questioning his treatment of the team and, like with Modell, his playcalling.

It did not take long for Modell to let go of Brown, who had accumulated a 46-21-1 record in the Modell era, having been to two championship games in his final two years with the team, winning one of them.

Brown would later go on to found the Cincinnati Bengals along with ten other owners, including the local Cincinnati newspaper. Famously, the Browns would not win a championship again.

No official Browns gear from that 34-year period between the brownie’s ban and the Browns’ banishment from Cleveland bore the elf, but unrelated merchandise did.

This includes the weekly recaps from the Cleveland Plain-Dealer, which employed a cartoonist to draw the brownie following games. The brownie’s general state would give readers a clue as to how the Browns did that week.

After Modell unceremoniously — and illegally — moved the team to Baltimore (a move illegal enough that the NFL allowed the city to keep the team’s intellectual property and claim its history), the refounding of the Browns in 1999 saw a gradual reintroduction of the sprite onto team gear.

First, a training camp logo. Then, as a sideline mascot. Then, on team gear worn by coaches. And then, as practice jerseys. And finally, painted onto the field.

The brownies are historical guardians, cleaning up messes and reaping what’s been sown.

Enter the Nisse

The thing about brownies is that they have a New World feel to them, relatively speaking. Their folklore runs much closer to the present day than the fantastical creatures we associate with myth — dragons, trolls, ogres and the like.

But they, too, have ancient roots. The Scottish-English tradition of diminutive protectors and caretakers of the home goes back to Germanic tradition, one that unsurprisingly touches base with Norse mythology.

Which is to say that the Vikings had their own Lilliputian guardians. The Nisse.

Perhaps not quite as terrifying as one imagines most of most Norse mythological creatures, but they occupy the same folklore space as the brownies do. They clean, organize and take care of critical tasks around the homestead.

And when disrespected, they can play pranks or worse.

Angering either a brownie or a nisse portends bad luck, and both franchises have seemingly been stung by that bug.

But it’s been the Browns who feel more cursed — the rare team that carries the greater burden of franchise misery over the Vikings. And they certainly felt that way after their game in Tottenham.

Carson Wentz, Comeback King?

Live feedback from fans on social media suggested that Wentz had a poor game against one of the league’s top defenses. But though he only threw for 6.9 yards per attempt (nice!), he was remarkably efficient and effective.

His success rate of 50.0 percent at the end of the game exceeded every other quarterback that played the Browns this season — a roster that consists of Lamar Jackson, Joe Burrow, Jared Goff and Jordan Love.