Guaranteed Money, the NFL, and What It Means for Labor Politics

A deep dive into the recent confidential decision regarding the NFLPA’s claim of NFL collusion to keep guaranteed money down.

Two weeks ago, journalists Pablo Torre and Mike Florio obtained a copy of the confidential decision that arbitrator Christopher F. Droney handed down when resolving the NFLPA’s claim of NFL collusion.

They found, in their eyes, strong evidence that the NFL illegally colluded to keep guaranteed salaries for NFL players down. The arbitrator disagreed, finding evidence that the NFL attempted to collude but failed.

This is meteoric, and the fact that the decision wasn’t made public was something that Torre and Florio broke down on Torre’s podcast — an episode well worth listening to. The decision is worth discussing, as are the broader implications for our relationship with labor and politics in the United States.

But first, let’s talk in broad terms. What is collusion, and why does it matter?

Collusion, Trust and Labor Law

Labor politics in the United States are weak compared to so-called social democracies in Western Europe, where labor politics have become more foundational to corporate governance and labor law.

When labor politics were stronger in the United States, antitrust legislation sped through the process to become law, updated on occasion to prevent such law from limiting labor unions in the same way they were supposed to limit monopolies.

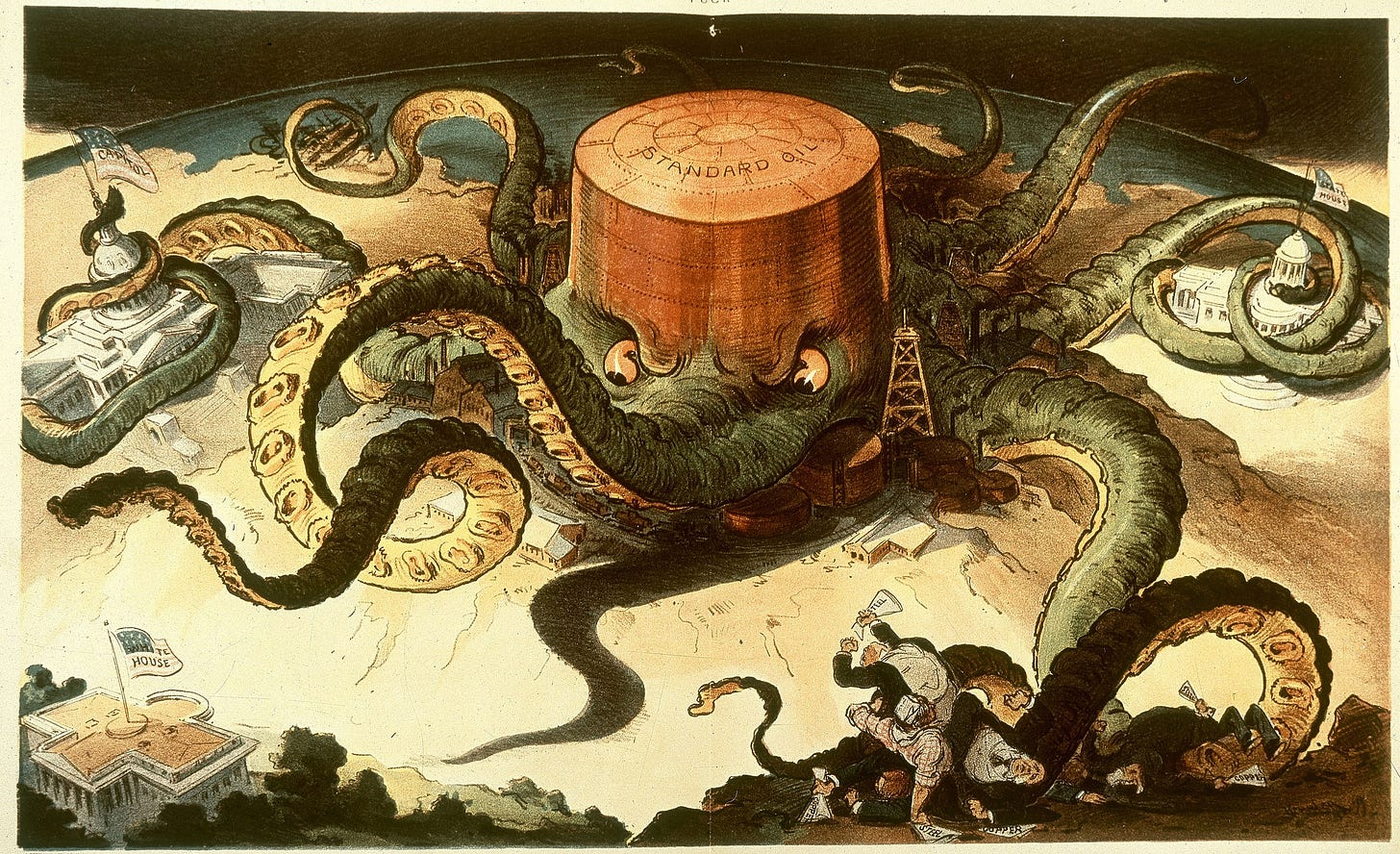

These laws, passed at the height of the robber baron era, were designed to limit the power of corporations that had taken over entire sectors like steel production (Carnegie Steel), rail (railroads operated by Cornelius Vanderbilt and Jay Gould), fossil fuels (Standard Oil) and more.

Those corporations had the unique ability to set prices without competition while reducing product quality. The promise from free market advocates is choice; choice that should force companies to lower prices while increasing quality. Monopolies erode that promise, raising prices and reducing quality.

These changes occur outside the scope of their impact on consumers; monopolies (single sellers) are also, generally, monopsonies (single buyers). Just like markets can be distorted when only one firm can provide a product to sell, markets can be distorted when only one buyer exists to purchase a product.

And monopsony power exists in the labor market for these mega-corporations. In addition to exercising their monopsony power to purchase the raw materials needed to produce their products (say, coke for steel or coal for rail engines), they are single buyers for labor in many of the communities they’ve set up shop in.

That allowed them to drive down the price of labor, especially in a mid-19th-century environment with limited labor movement across cities and without an enforceable minimum wage.

Antitrust law exists so that we don’t have just one place to buy our food, just one place to buy our televisions and just one place to buy our cars. When we’re talking about “quality,” we don’t just mean food that tastes bad or cars that need more maintenance. We’re talking about rotten food in the supply chain, electronic appliances with poisonous materials and cars without safety standards.

Monopolies erode safety by cutting corners in their products, resulting in fuller cemeteries and emptier cities.

Unfortunately, for antitrust legislation to be effective, there needs to be enforcement. The poor enforcement of these laws, seemingly intentionally, is one reason why we’re seeing a growth in monopolies governing elements like internet access, internet search (and ads), credit ratings, rural grocery and even syringes.

Antitrust law governs not only monopolies but also oligopolies. Oligopolies form when a few firms, instead of just one, have dominant control over the market and act in concert to engage in functionally monopolistic behavior. There are several well-known international examples of oligopolies.

The most well-known is OPEC, or the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. They cooperate to restrict the supply of oil or otherwise fix the price of fossil fuels, enriching their member states.

In the United States, if we had evidence that ExxonMobil, Chevron and Marathon were cooperating to raise the price of gasoline, that would violate antitrust law. Oligopolies carry much of the same risk that monopolies do, although there is a significant chance that members of an oligopoly will “cheat” on the agreement without some sort of mechanism to punish cheaters.

Oligopolies coordinating like this is called collusion.