Has Legalized Gambling Poisoned the Sports Atmosphere?

Football fans have been flooded with ads for gambling and fantasy products. What has been the impact of legalization on the people who gamble, the fans who don't and the players who play?

Anyone following the NFL over the past few years has found themselves inundated with ads for sportsbooks and fantasy football apps. The fantasy games that we’re being targeted with are nothing like the redraft season-long leagues we’ve become used to or even the more familiar daily fantasy games that flooded the airwaves several years ago.

Instead, we're assaulted with ads for "pick 'ems," where participants attempt to guess whether a player will hit "more than" or "less than" a particular statistical milestone (say, 62.5 rushing yards in a single game). These are legally distinct from gambling on "overs" or "unders" but, aside from a few technical details, are functionally identical.

For most of these companies, the lines — the milestones these guesses are built around — even move in the same way as the over/under props do in traditional sportsbooks.

The development and introduction of sports gambling into regular football consumption has fundamentally altered the landscape of the sport. And that’s a problem.

This is not written from a place of judgment against those who gamble, play pick ‘em pools or daily fantasy. I currently have fantasy accounts with six different apps and have enthusiastically entered (the same) thousands of dollars into those contests. When I briefly visited New York over the summer, I took a 12-minute detour to New Jersey, where I laid hundreds of dollars into season-long props on the NFL and CFB seasons.

In fact, it behooves me to keep this hype train going. In addition to these companies bankrolling my non-Substack ventures, I have made a profit from these games personally. On top of that, I can turn my participation into sponsorship deals.

I have been approached for that very reason. The array of sponsorship opportunities are dizzying. I can keep a permanent banner on this site, create specific sponsored posts, generate weekly lineups with invites for readers to compete or simply post about these sites on social media. Each tier of participation has a different payout.

Unfortunately, I have had to turn them down because, after a back-and-forth with their legal departments, pieces examining the fantasy and sports gambling space run too close to violating partner disparagement clauses. With that, I have turned down tens of thousands of dollars.

It is important to note that the gaming landscape is diverse in what it offers. Many companies offer both a sportsbook and fantasy options. Those fantasy options can vary widely in how the games are played and this gives some of them legality in some states but not others. What emerges is a patchwork of results where every state has a different set of products on offer, making it difficult to nail down what is fantasy and what is gambling.

My discussions with multiple companies offering to sponsor Wide Left has made it clear that these distinctions are important; indeed, they are critical to the survival of some of these companies. To understand this distinction, it’s important to dive a little bit into the history of regulated online gaming.

How Did Online Poker Turn Into AI-Powered Fantasy Football?

In 2003, an accountant named Chris Moneymaker – I promise that’s his actual name – splashed onto the poker scene after securing an entry into the World Series of Poker’s Main Event after winning an online poker tournament.

His win in the online tournament provided him with a bid in a satellite tournament hosted by PokerStars – one of the premier online poker sites – and the win there gave him his ticket into the Main Event, with an entry fee of $10,000.

Oral histories will attribute a good deal of poker’s rise in popularity to Moneymaker’s run. They’re probably correct. But in my recollection, Moneymaker wasn’t the sole cause of the popularity of poker.

It was the first year ESPN televised the tournament in earnest (instead of as a tape-delayed, documentary-style broadcast with no commentary) and it feels ridiculous to deny the impact that the Worldwide Leader would have on poker’s visibility, with or without a just-so underdog story. The innovation of the “hole cam,” the camera that allowed broadcasters and viewers to see what cards every player had, was crucial in capturing audience interest.

Of course, my recollection could be marred by replays on ESPN of the tournament and discussions that middle schoolers would hold in real-time for events that had already passed. The combination of all of the factors involved in poker, Moneymaker Effect or not, resulted in huge gains for poker.

In 2002, there were 632 entrants into the tournament’s Main Event. In 2003, the year that Moneymaker entered, there was a bump up to 839 entrants. But in 2004, the year after his highly public victory, there were 2,576 entrants. By 2006, there were 8,773 entrants.

That year would be the peak until 2023, during another revival of the poker scene. There’s a reason for that localized maximum peak in 2006 instead of 2007 or 2008.

Moneymaker’s success sparked interest in the online poker community – so much so that it was called the “Moneymaker Effect.” The former accountant, himself inspired by a different cultural poker phenomenon (the movie Rounders), was sponsored by the website that punched his ticket – PokerStars. They, along with Full Tilt Poker, Gutshot Poker, PartyPoker and many others, would explode with new membership.

Poker websites hadn’t been particularly mature through the early 2000s but had developed just in time to absorb the boom and enable sharp players to make significant money. That influx of players, isolated from the realities of playing in person, could focus on odds and performance tracking.

Quickly, tools like heads-up displays were developed that gave players access to the history of every decision made at a table by every participant, as well as running odds on the likelihood of winning a hand based on the state of the table.

Some players would play dozens of tables at once and would train themselves to ignore the graphics on the screen – instead focusing on the text overlays from third-party programs to quickly determine if they wanted in on a table’s action without having to pay attention to it. This way, they would fold the vast majority of their hands and opt into only the hands with good odds of success.

These tools weren’t magic, and the reason players had dozens of games up is that it required quite a number of hands, played again and again… and again and again… to start accruing a profit. Many online poker players turned it into a job, eking out a living by tracking the numbers on the screen for small but steady gains by playing the odds and pouncing on small edges hand by hand, table by table.

It was a short-lived boom. The online poker scene took an enormous hit in 2006 when Congress passed the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006, banning online gaming – poker, sports betting, online blackjack and more – in states where those games were banned locally. Prior to this, those in New York couldn’t walk into a casino to play poker but could sign up online to do so.

Crucially, the law carved out fantasy sports – “a game of skill.”

One impact of this legislation is the explosion of alternate sites hosted offshore with similar domains. For a brief time, websites like PokerStars would advertise their free, legal and non-gambling poker site, PokerStars.net, with the understanding that interested parties might end up at PokerStars.com instead.

Once there, users would have to find a way to fund their account – US banks were prohibited from working with these websites, as were US-based payment processors. Before cryptocurrency, this meant creative tools to move money offshore and then into those sites.

It didn’t stop people from gaming online but it inhibited it significantly. Nevertheless, poker limped along with these simple bait-and-switch advertising tactics – neither illegal or honestly unethical on the surface, but enabling behavior that violated various state laws against online gaming — often unbeknownst to the players themselves.

It all came to a head on April 15, 2011 – known in the poker world as “Black Friday.”

Full Tilt Poker, PokerStars and a number of other online gaming companies were indicted by the federal government for a host of crimes related to the UIGEA, including money laundering and bank fraud. This was no slap on the wrist either; the federal government shut down the websites in question, threatened a number of executives with jail time and extracted billions in fines.

This was such a significant move that it invited international protest, as Antigua and Barbuda, which hosted a number of online gaming platforms, extended a suit from 2003 about the United States’ shutdown of online gaming platforms to include new sites impacted by the poker shutdown.

Antigua and Barbuda won, for what it’s worth. Instead of engaging in authorized retaliatory action against the United States government, they sought a settlement payout worth millions of dollars. They still have not received it.

Regardless, this wiped out the online poker community. Those in the know could find ways to play; offshore sites would attempt to fill in the void — thus the rise of Bovada and Ignition — but there wasn’t a large pool of new players to take advantage of. Sharks without fish.

So, what did all of these online poker mavens, conversant in modeling and statistics, turn to?

Sports.

Traditional sports betting was difficult for all of the reasons online poker was difficult. And, on top of that, casinos had the goods on most of the odds. It was difficult to find an edge.

But the loophole in the law that allowed fantasy sports gave those same players an out. This led to the development of “daily fantasy” from websites like DraftStreet, DraftDay, StarStreet, DraftKings and FanDuel. Daily Fantasy, or DFS, offered an accelerated version of traditional fantasy sports, a model where users would draft or bid for players on a team whose lineup would remain largely static throughout the season.

This novel way to play would give players a chance to furnish a completely new lineup every day, possibly mere moments before a new slate of games. Many of them used a salary cap method, with the host site assigning a dollar value to each player and a dollar limit to each roster.

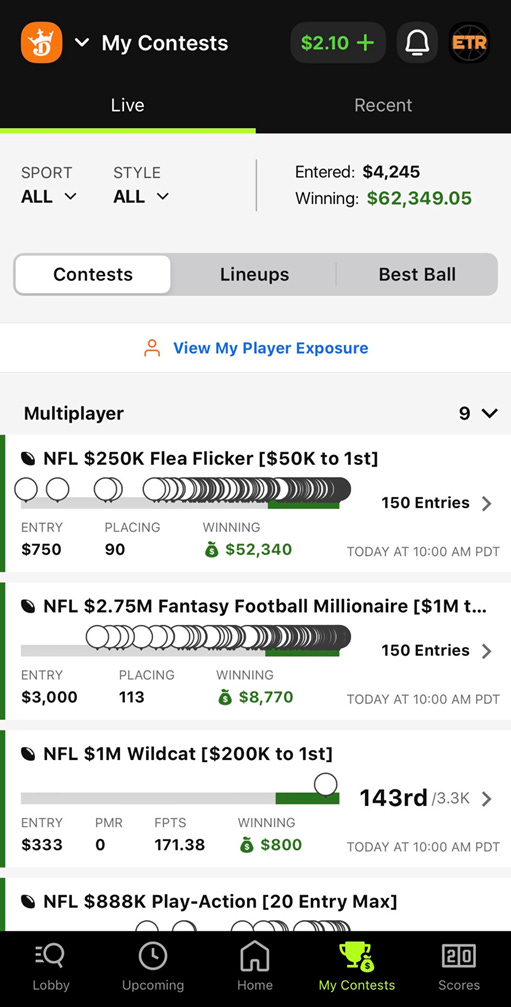

There were two primary contest types – cash and GPP (guaranteed prize pool). Cash contests pay out (about) 50 percent of participants; the most common cash contest format pits just one player against another in a head-to-head. That player could be random or selected through the lobby system.

GPPs are tournaments that only reward a small portion of the participants – often ten percent or fewer. Dozens, hundreds or even thousands of players would pay an entry fee that gave only the top scorers substantial payouts. That’s where events like the “Millionaire Maker,” guaranteeing the top participant a million-dollar payout, come from.

While homebrewed model-making couldn’t compete with sportsbooks, it could compete with the vast majority of the participants entering GPPs after the explosion of daily fantasy. The sharks had found their fish.

This flight from online poker to daily fantasy isn’t some imagined narrative – the concept was developed by a former online poker player named Chris Fargis and the terminology used by these sites and those who make content about daily fantasy is steeped in poker language. The owners of these sites are often former (or current) poker players. As Jay Caspian Kang pointed out:

The D.F.S. industry is still inextricably tied up in those poker roots. Players talk about “tilting” because of “variance,” especially when a “fish” puts in a “donkey” lineup that ends up going crazy. (In regular American English, this translates roughly to “I am really mad because some idiot punched in some random lineup that ended up catching every conceivable break and beating me.”) And it’s not only the former poker players who talk like this — when I first spoke to Nigel Eccles, the C.E.O. and founder of FanDuel, he referred to the different denominations of D.F.S. games as “tables,” in the same way a pit boss at a casino might point you to the $10 blackjack or the $25 baccarat tables. Rotogrinders, by far the biggest site for D.F.S. discussion, commentary and content, was founded in part by Cal Spears, a former poker player from Tennessee who used to run an online forum for poker strategy called PocketFives. Jonathan Aguiar, DraftKings’ director of V.I.P. services, is also a former poker player known as FatalError. Fargis, too, now works at DraftKings.

These daily fantasy contests would come under heavy fire after a blitz of advertising from the emergent duopoly of DraftKings and FanDuel. Leagues and media would partner with either of the two sites – who had either bought out their competitors or were content to watch them die on the vine – providing daily fantasy content alongside their typical fantasy discussions.

Several states took a different view of fantasy sports than the federal government, arguing that these were, in effect, online gaming and not “games of skill.” The fact that the same players emerged at the top of the rankings time and again was unpersuasive. After all, that’s also true of poker. And that’s not legally a game of skill.

There are massive imbalances in daily fantasy. Several analyses had emerged during the daily fantasy boom that quantified this imbalance; the New York Attorney General found that nearly 90 percent of players had a negative return on investment. A McKinsey study found that 1.3 percent of players had earned 91 percent of the prize money.

Top players earned these massive prizes using both formats. GPP grabbed headlines, where high-volatility strategies that use multiple, correlated tactics are virtually the only way to win. Top players entered hundreds of entries with optimized lineups.

Most of the entries didn’t win any money, but that doesn’t matter – placing 100th and placing 1000th were the same. The key is that they placed in the top ten percent often enough to earn a profit, while retail players were entering in just two or three unoptimized lineups.

The same, however, occurred in cash games, where the top half take home the prize. In head-to-head contests against single players, sharks flooded the entry market so that participants without tools to enter multiple lineups would more often than not be paired against experienced players. In cash tournaments, where the top half won, career players maxed out entries.

On top of that, high-level players had access to tools that others did not. Injury news would result in thousands of automated lineups changing at a moment’s notice because of scripting software deployed by professionals. Typical players couldn’t respond to injury news this quickly.

Daily fantasy participants, in essence, were being sold a fair game while playing a rigged game. When entry limits and scripting controls were proposed, DFS platforms decided against the practice – even loosening their restrictions on certain types of scripting in order to appease their big players.

As Kang points out, poker has natural controls to prevent professionals from regularly gouging newcomers and preventing fresh blood from coming into the sport. Beginners play at small-stakes tables and play against the variety of players who happen to show up on that night of play – not a professional gambler playing seven of the eight hands.

With the ability in DFS to enter as many contests as possible, sharks could prey on low-stakes entries alongside their appearances in the million-dollar contests.

Oversaturation and, perhaps, this profound sense of unfairness may have killed the DFS craze. But not-gambling gambling on sports didn’t die with DFS. Instead, pick contests – where fans would pick “less than or more than” for certain statistics like rushing yards – took their place.

These are, these fantasy sites tell us, not prop bets. After all, at a sportsbook, you can place a prop bet on a single player’s statistics and ride that line. Here, you not only have to do so with multiple players, they have to be on different teams (or, in some cases, in different games).

And the payout doesn’t come from the company like it would a casino – instead it comes from other players entered into automatically generated tournaments. The fantasy house simply takes a portion of the winnings in that tournament, just like in DFS.

This is, of course, an accounting trick. Sportsbooks also use losing bettors’ money to pay out winning bets with a little off the top. But, as anyone who follows the NFL salary cap knows, accounting tricks matter.

One could parlay enter a full-send pick ‘em tournament, where every pick has to hit in order for the player to earn any payout, or they could take a reduced reward and enter a flex tournament, where they can miss one, two or even three legs and still find a modest payout.

Sportsbooks Followed Suit

Gambling has been embedded in the sports landscape, both in legal and illegal forms. The advent of the injury report, for example, was designed to limit insider advantage when it came to betting on games.

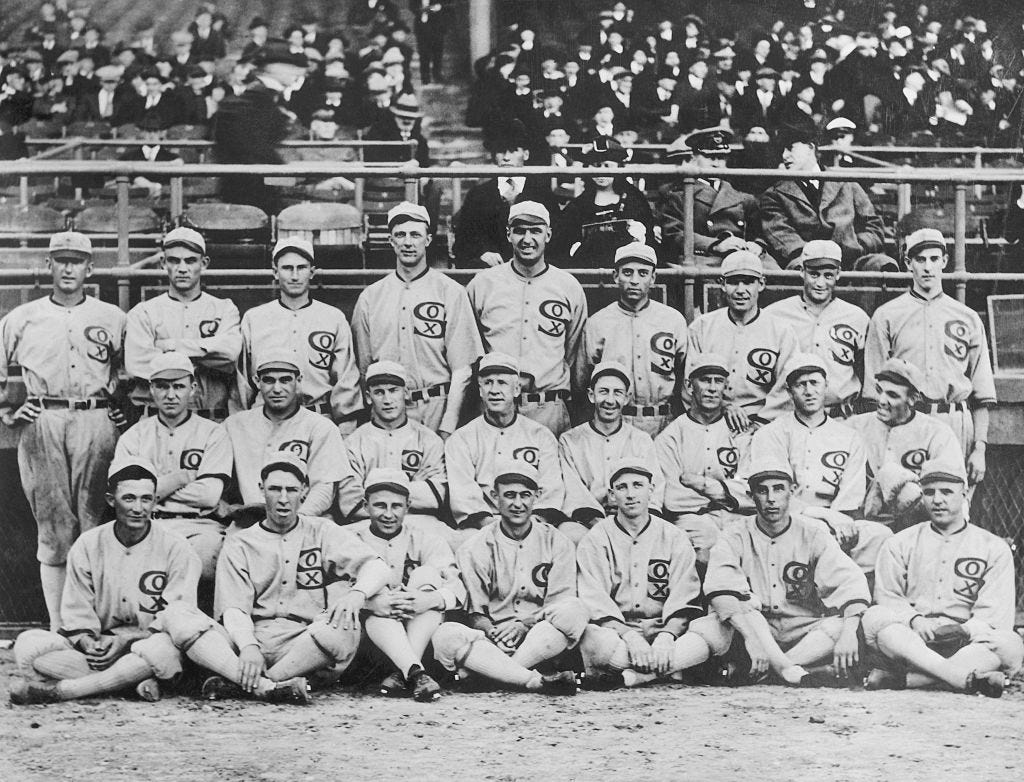

The initial history of gaming is marked more with scandal than anything else, with the infamous 1919 Black Sox defining the common understanding of that relationship. College and professional games, not well-monetized at the time and therefore subject to outside influence, were rife with illegal gambling interests influencing outcomes.

In 1931, Nevada legalized all gambling, establishing an initial jurisdiction for gaming as a state-level concern. Sports betting, still largely conducted in the black market, was only legal in casinos. However, increasing concerns about organized crime led to federal intervention – first a heavy 10 percent tax in 1951, and ten years later, a ban on the use of wire communications for interstate gambling.

Those combined to functionally kill legal sports betting until 1974, when the tax was reduced from ten percent to two percent, allowing casinos to reopen sports books. That tax was later reduced from two percent to 0.25 percent.

Because no other states explicitly allowed sports gambling, the 1992 Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act functionally made the practice illegal at a federal level outside of Nevada, with some carve-outs for horse racing, dog racing and, for some reason, jai alai.

New Jersey, who had an opportunity to legalize sports betting in their own state before the passage of PASPA but failed, sued the federal government over this law, arguing it violated the rights of federalism enshrined in the Tenth Amendment.

Winning that lawsuit in 2018, states were free to craft their own rules about gambling. They approached this in typical patchwork fashion, with some states legalizing some forms of gaming but not others, while some states developed their own definitions of gaming – whether fantasy sports were included, for example.

Gambling, Paperclips and “Artificial Intelligence”

Fantasy promotions run in a wider number of states than gambling promotions do. That legal distinction hasn’t prevented them from introducing users to anti-gambling tools – while there’s something vaguely commendable about this, it gives the game away: this is, psychologically speaking, gambling. In theory, the reason we have anti-gambling laws at all is because of that concern.

And fantasy companies are doing everything they can to put fuel on that fire.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Wide Left to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.