Inside The Vikings' 19-Play Touchdown Odyssey

The Minnesota Vikings relentlessly asserted their will against the Washington Commanders for 12 minutes on Sunday. Matt Fries breaks down how they did it, play by play.

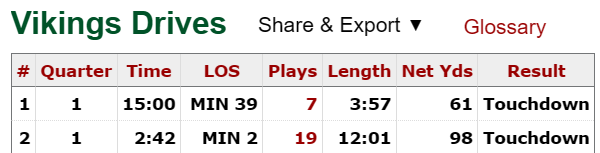

Touchdown, 19 plays, 98 yards, 12:01, WSH 0 - MIN 14.

In 52 characters, ESPN’s Game Center blandly summarized one of the most dominant drives of the season, one the Minnesota Vikings put together in last Sunday’s game against the Washington Commanders.

Pro-Football-Reference offers a similar breakdown in the form of a table:

Like a picture, there are a thousand (more, if this article is worth anything) words contained within that drive. This was a journey on a scale that is rarely seen at the NFL level.

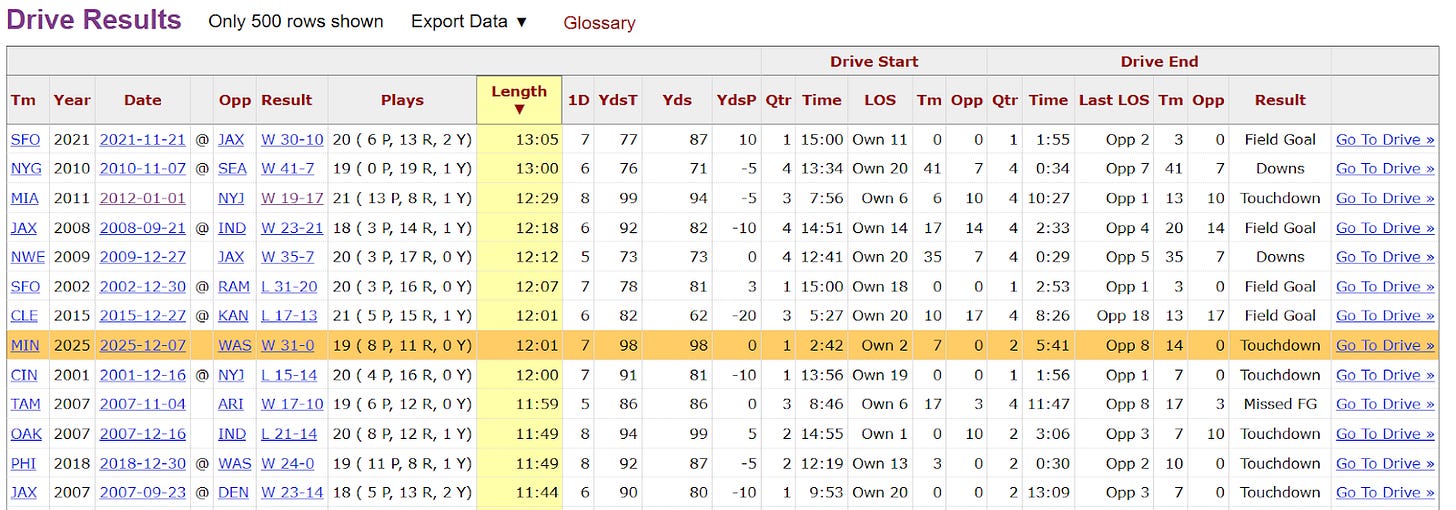

PFR tracks drive data going back to 2001. Since that time, the Vikings have never had a drive that involved more than 19 plays, although they did hit exactly 19 two other times since then (December 14th, 2003, against the Chicago Bears and September 21st, 2008, against the Carolina Panthers).

Both of those drives ended in field goals, which means they don’t quite match what we’re looking for: a field goal counts as a play. On those drives, the Vikings ran 18 offensive plays and 1 special-teams play, whereas on this drive they ran 19 offensive plays. So, by plays, this is the longest TD drive that we know of in Vikings’ history.

Across the NFL, there have been 81 drives of 19 or more plays since at least 2001, and only 31 of them have resulted in TDs, fewer than one per team. The longest drive in terms of plays was a 24-play New Orleans Saints drive in 2007, while the longest touchdown drives took 21 plays, something that has happened 4 times.

Then there’s the element of time. The Vikings started their drive with 2:42 left in the first quarter and scored with 5:41 left in the second, nearly erasing a whole quarter. That’s the most time a drive has taken up since San Francisco in 2021 (who have the longest recorded drive, taking up 13:05 on 20 plays), and ranks 8th longest among all drives. It’s third among drives that did not involve a penalty, and second among drives that ended in a TD, behind only the 2011 Miami Dolphins.

This drive didn’t quite rise to the level of the epic that was Navy’s 26-play, 14:42-minute drive against New Mexico in the 2004 Emerald Bowl, but it comes close. A first down instead of an 8-yard TD run at the end may have pushed it into that territory. As such, it’s worthy of a full breakdown. Let’s dive deep into what happened on that drive.

The Drive

Play 1 - 1st and 10 at the Minnesota 2

Play Result: Jordan Mason up the middle for 4 yards (tackle by Bobby Wagner and Von Miller)

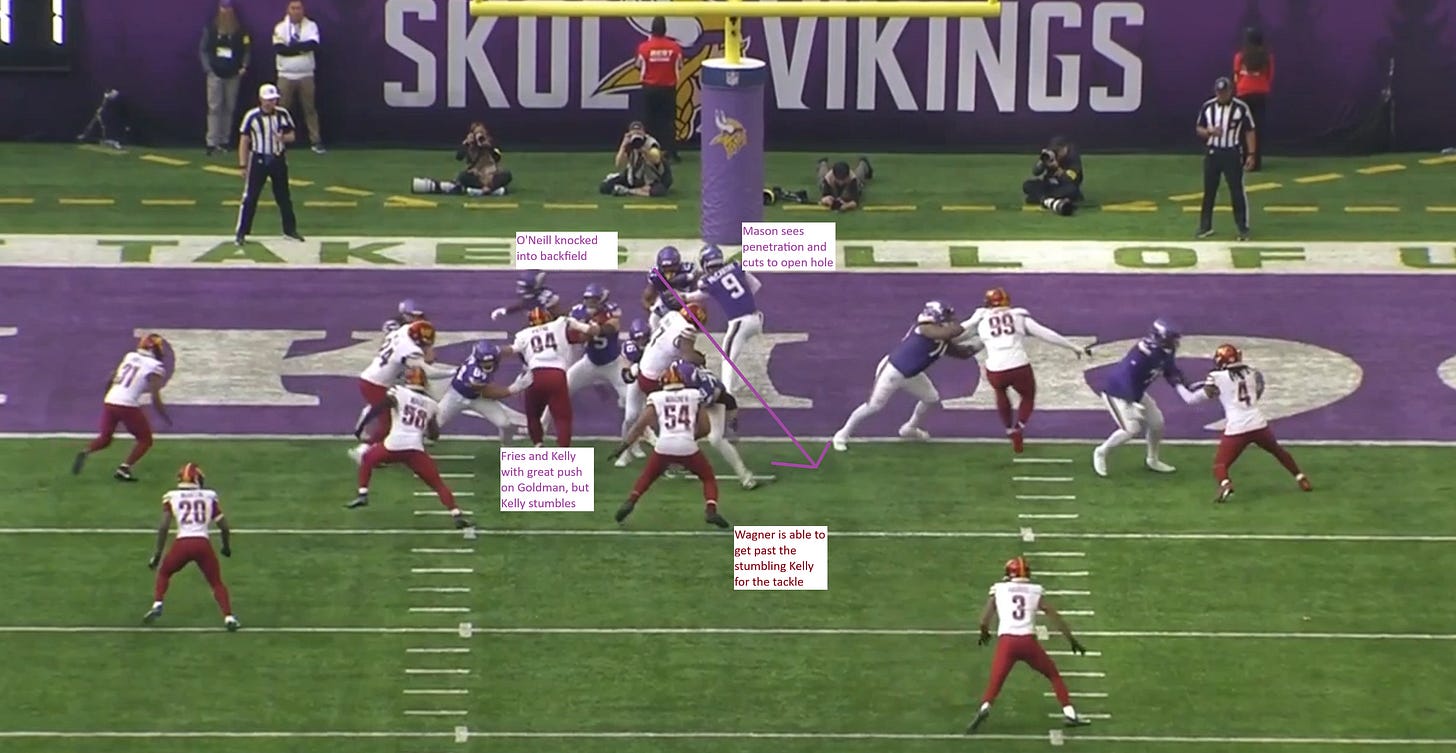

The Vikings started off the drive backed up at their own two-yard line after forcing a turnover on downs by Washington. The Vikings run inside zone out of the I-Formation. Fullback C.J. Ham kicks outside to block the corner, and the play design may take running back Jordan Mason to Ham’s path initially, but he quickly recognizes the knockback that right tackle Brian O’Neill generates against defensive tackle Daron Payne.

Mason turns his eyes upfield, where right guard Will Fries and center Ryan Kelly have executed a great double team block, knocking nose tackle Eddie Goldman up into the air as he attempted a swim move and driving him back, climbing up to linebacker Bobby Wagner.

This leaves a wide hole for Mason, and while Kelly trips on his way to Wagner, who makes the tackle, Mason is still able to grind out a respectable 5-yard gain to give the offense some breathing room.

Play 2 - 2nd and 6 at the Minnesota 6

Play Result: Jordan Mason left guard for no gain (tackle by Bobby Wagner)

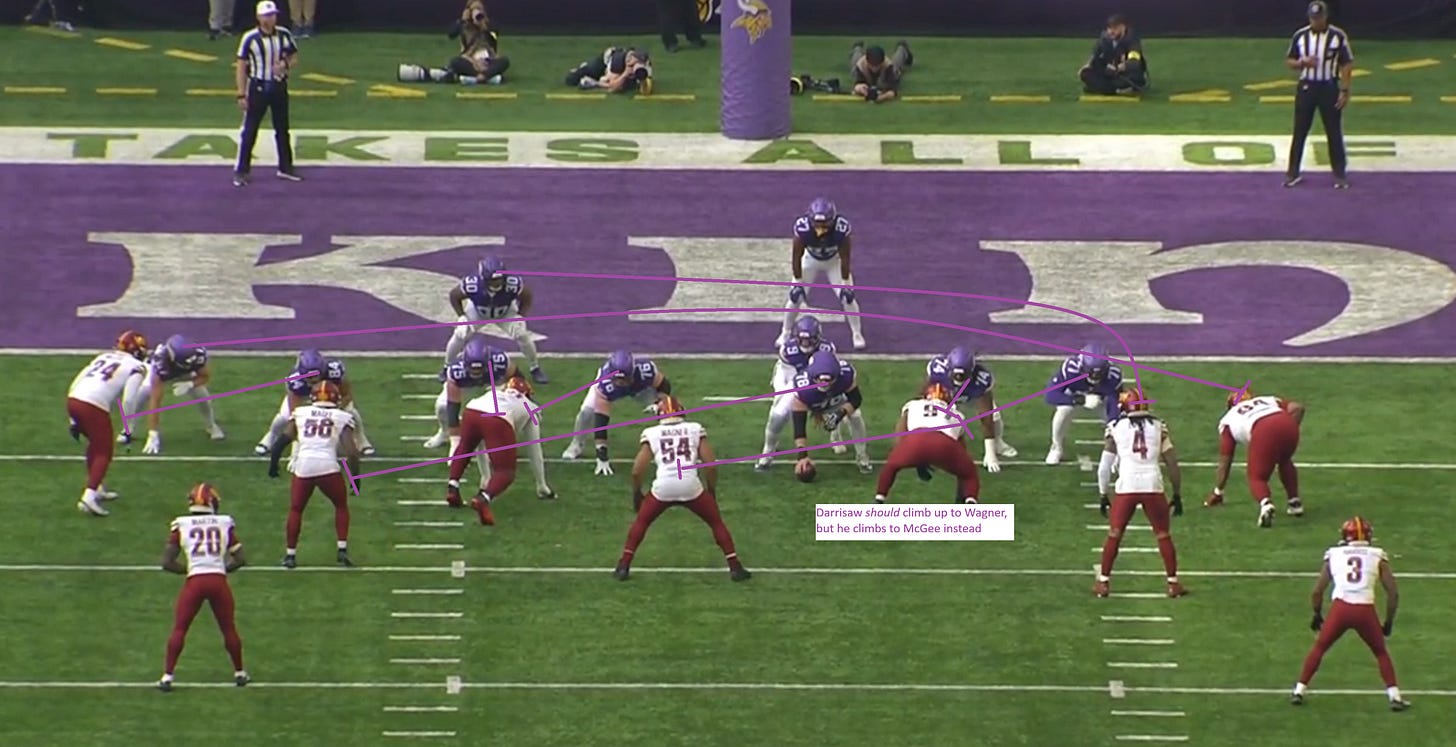

On the second play, the Vikings run a play that looks like split flow zone but also has counter elements. On the play, tight end T.J. Hockenson comes across the formation to kick out the opposing defensive end, and Ham wraps around to linebacker Frankie Luvu as a lead blocker. On normal split zone, you only have one player crossing the formation to take on the backside defender on a zone run, but typical counter plays have a lineman pulling.

Either way, this play gets messed up by a run ID issue. Both Kelly and left tackle Christian Darrisaw climb up to linebacker No. 58 Jordan McGee. I believe Darrisaw should come off of his double team with left guard Donovan Jackson and block Wagner, who ends up unblocked on the play, and makes the tackle for no gain. Ham can’t block both Wagner and Luvu.

Play 3 - 3rd and 6 at the Minnesota 6

Play Result: J.J. McCarthy scrambles up the middle for 7 yards (tackle by Frankie Luvu)

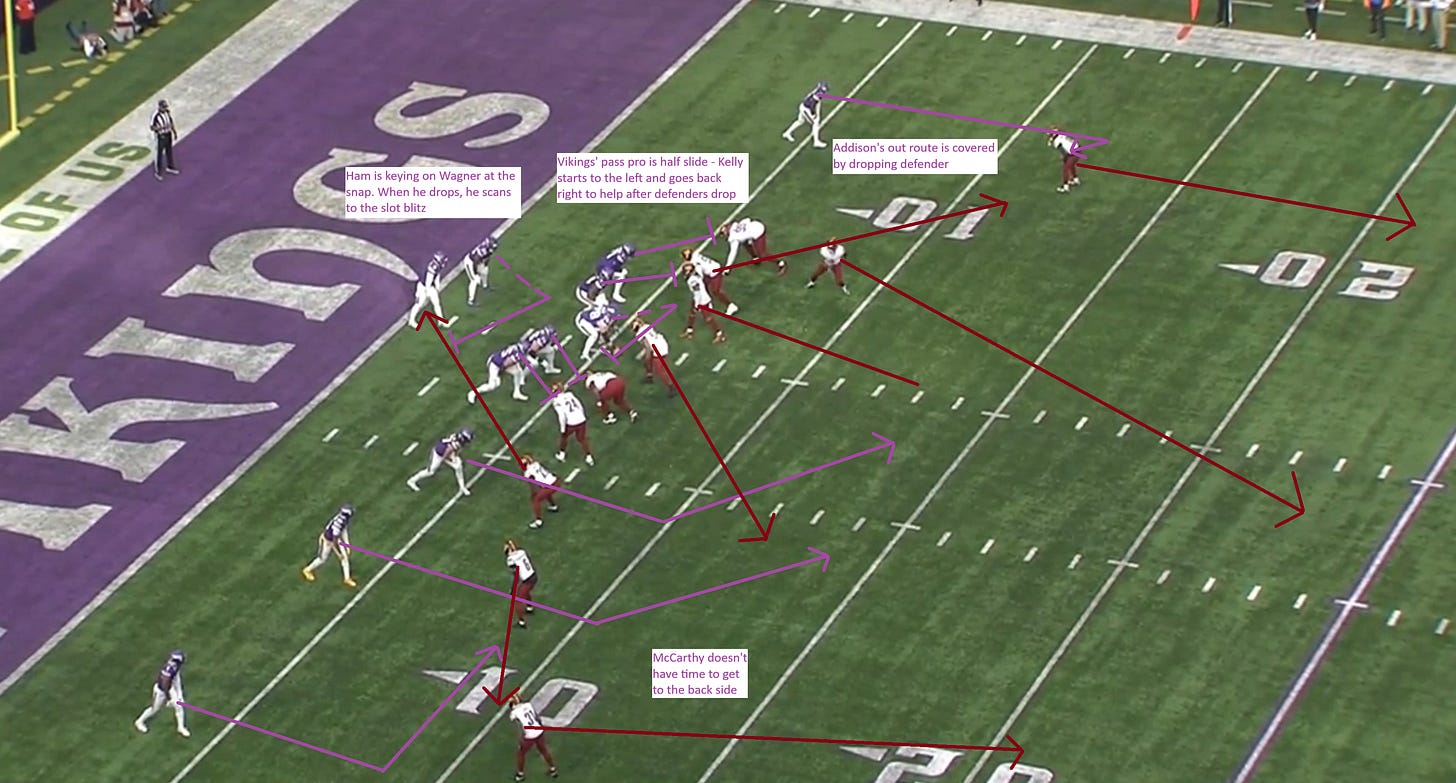

The Vikings now face 3rd down, and J.J. McCarthy has his back foot at the goal line as he lines up to take the snap against a Cover 0 look from Washington. Safety Will Harris drops to the deep middle right before the snap, and three other defenders soon drop into coverage. Where there were seven pass rush threats, now there are three against the Vikings’ six blockers.

But wait. There are actually four pass rush threats on this play. After dropping three players, Washington added slot defender Quan Martin to the rush. He’s not accounted for in the protection, and an offensive lineman doesn’t pick him up.

That leaves Ham, who was scanning the middle of the line, to get all the way to his right and make a tough block, or Martin would have a free run at McCarthy. Ham does just that, and great pass protection from him means McCarthy avoids the sack.

As far as the pass play goes, wide receiver Jordan Addison runs a curl at the top of the formation. Cornerback Mike Sainristil gives him a wide cushion, but linebacker Jacob Martin is buzzing underneath the route as he drops from the line of scrimmage.

I think you could argue that a throw the instant McCarthy hits the top of his drop might beat Martin to the spot, but I understand McCarthy not throwing it. Instead, he’s able to scramble out of the pressure and dives forward for the first down.

Play 4 - 1st and 10 at the Minnesota 13

Play Result: Jordan Mason left end for 2 yards (tackle by Javon Kinlaw and Bobby Wagner)

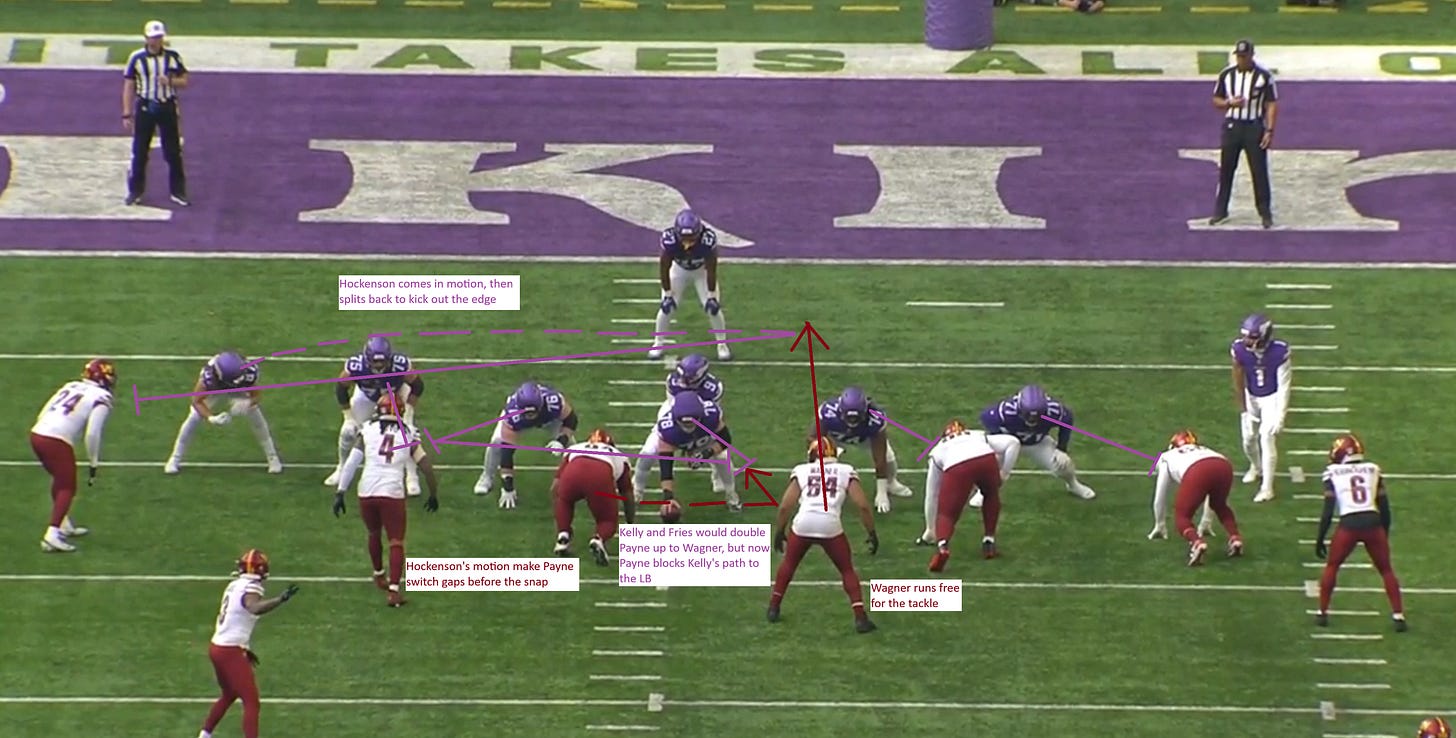

On the ensuing first down, the Vikings ran the ball again. Hockenson motions before the snap, then cuts back at the snap on another split zone rep. That motion, unfortunately, helps create a blocking identification issue with the front.

As Hockenson motions, Payne shifts from the A gap between Kelly and Fries to the opposite A gap, between Kelly and Jackson. In the original formation, Kelly would climb to Wagner while putting a hand on Payne to help Fries reach block him.

With the new formation, each of Darrisaw, Jackson, and Kelly has a player outside their left shoulder, meaning they each need to reach block that player and there’s no real potential for a double team. This leaves Wagner unblocked once again, and the run goes for just two yards despite Darrisaw and Jackson clearing a wide hole.