J.J. McCarthy and "Waiting for the Cement to Dry"

The Minnesota Vikings have pushed their chips into a quarterback who needs to develop. We explore if its remotely possible and why it is such a problem.

This week, Wide Left did not publish a post-game recap of the Bears-Vikings game, one that would, theoretically, involve a discussion of the holistic effort produced in a win or a loss — identifying players who played well and those who played poorly. The Vikings' 19-17 loss may have many authors, but there’s only one worth discussing: J.J. McCarthy.

I opted out of a longer game analysis to do a deeper dive into McCarthy. He is a player whom head coach Kevin O’Connell said during a KFAN interview on November 18, “we’ve got to start seeing the cement dry on some of the things that we’ve worked really hard to make football habits for him.”

Cement is a binder in concrete, and it doesn’t dry; it cures. Later in the interview, O’Connell refers to it as concrete instead of cement. Either way, the analogy is well-received.

At the moment, McCarthy’s habits are not set in stone, as it were. His play is bad and degrades over the course of games, something that was evident throughout the most recent outing against the Chicago Bears.

The Bears are not a good defense. Against teams not named the Vikings, they have given up 27.5 points per game, which would be the third-worst performance in the NFL over a full season. They have allowed 2.48 points per drive and 0.07 EPA per play to non-Vikings opponents, marks that rank fourth and sixth-worst in the NFL.

This is not a product of a killer schedule either; it is a cohort that includes the New Orleans Saints, Dallas Cowboys, Las Vegas Raiders, the Washington Commanders, a non-Lamar Baltimore Ravens and a non-Burrow Cincinnati Bengals.

The Vikings have averaged just 23 points per game, 1.76 points per drive and minus-0.16 expected points per play against this bad defense — these last two marks would rank 29th and 30th in the NFL on their own, respectively.

The offense was awful, and it’s not because of the running game. The Vikings could not throw the ball.

And McCarthy is the reason.

The Vikings and the Curse of Choice

The Vikings are staring down the barrel of their choices — decisions that can only be justified with long-term outlooks, discussions about playing the odds and fleeting references to Josh Allen, Jared Goff or Matthew Stafford’s rookie years in the hopes that one can use just-so stories to beat the odds.

That feels like a distant possibility; for most of the game, “Nine” had been dueling with his own passer rating in a battle over the higher number.

For most of his early NFL career, McCarthy had been offered a platter of excuses; promissory notes, really, to be paid back later with good performances. Those performances so far haven’t come, while the excuses have withered away; all of his receivers have returned to the lineup, the offensive line is about as healthy and performant as most offensive lines around the league and the running game — underutilized as it is — is effective and efficient.

We do have a new set of excuses, of course. His hand is legitimately injured, and his receivers dropped the ball five or six times against the Bears this week, depending on who’s doing the counting.

But it is pretty remarkable that very few fans — some of whom were ardent in their arguments about McCarthy’s supporting cast inhibiting his ability to produce — no longer feel empowered to provide a runway for a young quarterback.

Minnesota has, ostensibly, one of the best receiver groups in the NFL — if not the best. But this group has underperformed in ways not connected to the quarterback. Whether that’s poor effort on plays or a surprising drop rate on passes they typically reel in, it’s not as if they have been succeeding to the degree we expected.

But now those excuses aren’t landing among the fanbase. To really underscore that fact, it is astounding that a six-drop game from receivers has lent McCarthy almost no latitude among fans. And, of course, a no-drop game would have resulted in something like 7.0 yards per attempt — an unreasonable amount of forgiveness to generate a result that is still below-average.

It is important to provide context for all performances, and if we measure them by statistics like completion rate and yards per attempt (or expected points), we should bring up these challenges. But it seems as if a good chunk of the Vikings fanbase has transitioned from arguing that the mistakes absolve him to agreeing that the amount of leeway they provide is not enough to explain his poor performances.

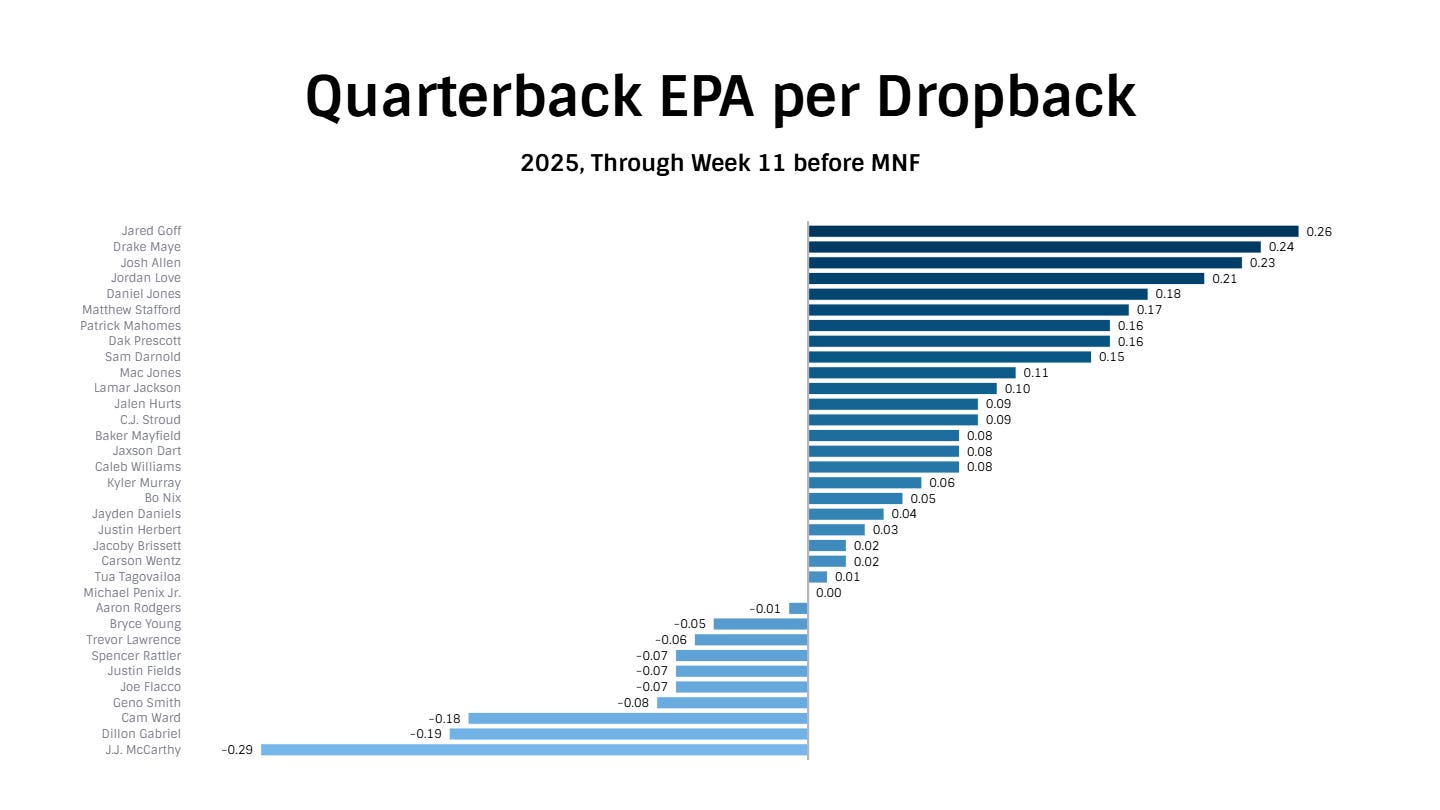

McCarthy is simply playing at a level well below his peers. The chart above doesn’t account for rushing, which does give him a boost, but it’s clear that the problems with his passing aren’t just a product of unfortunate environmental variables.

He has the highest drop rate from his receivers in the NFL by multiple measures — SIS and PFF agree. After accounting for that, he still has the worst or near-worst accuracy in the NFL. PFF’s adjusted accuracy rate, which eliminates spikes, drops, batted balls and other complicating factors, ranks him 34th of 36 quarterbacks.

His SIS “off-target rate,” which accounts for drops and spectacular circus catches, is the second-highest of any first-round pick in the past decade. The highest belongs to Anthony Richardson.

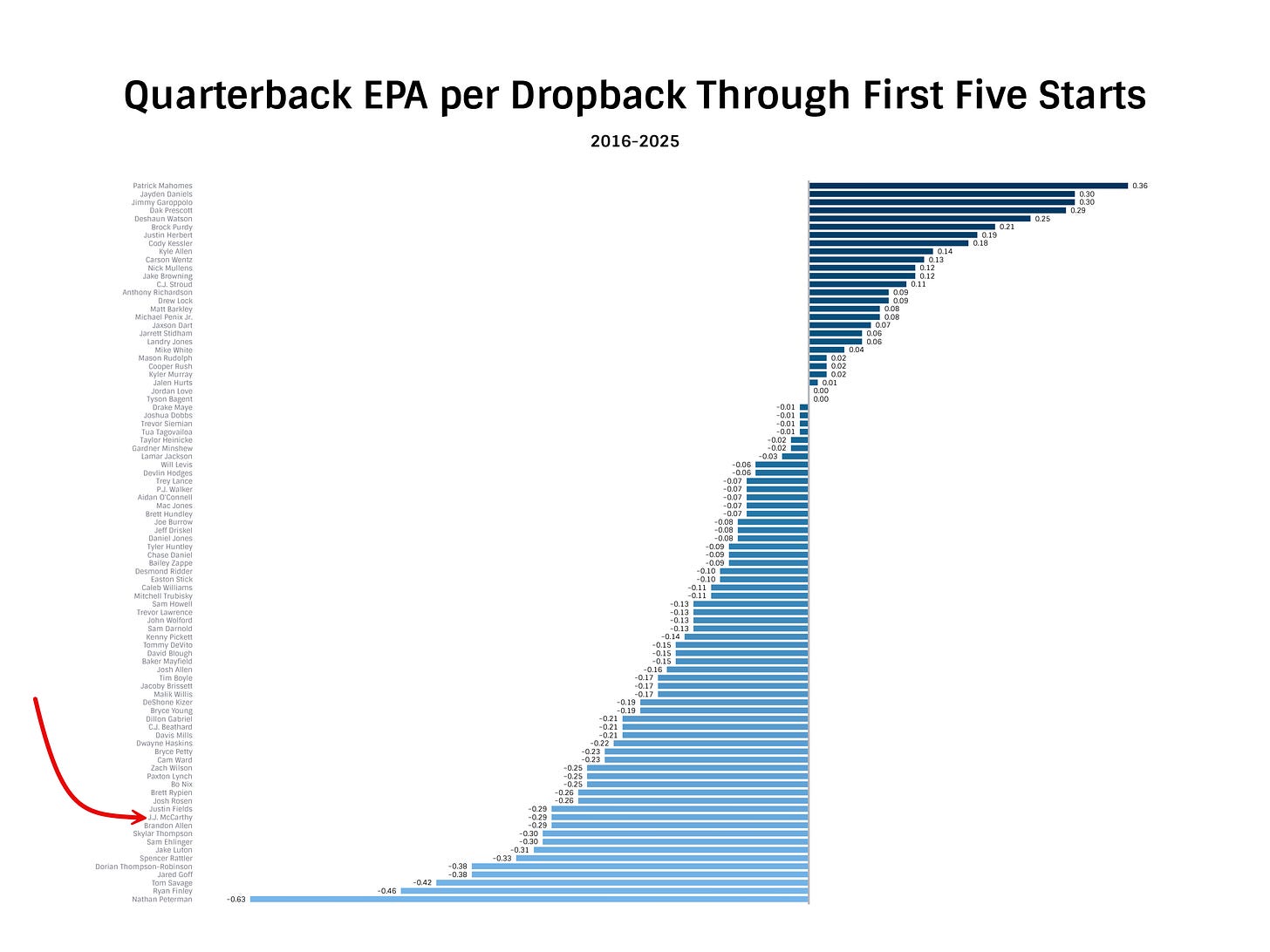

And it’s not easily explainable as purely a product of early NFL play. Against other quarterbacks over the past decade in their first five starts, McCarthy is a bottom-level performer.

Oh, That Looks Bad

It sure does!

Is there room for hope? Of course there is.

Let’s Talk Production

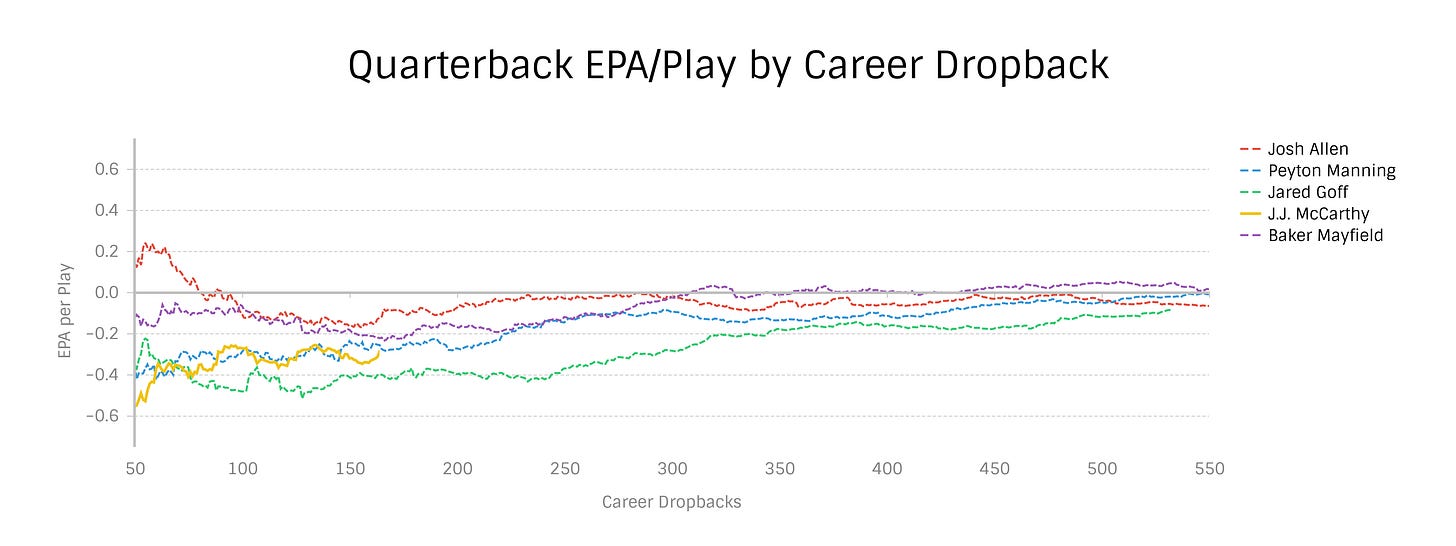

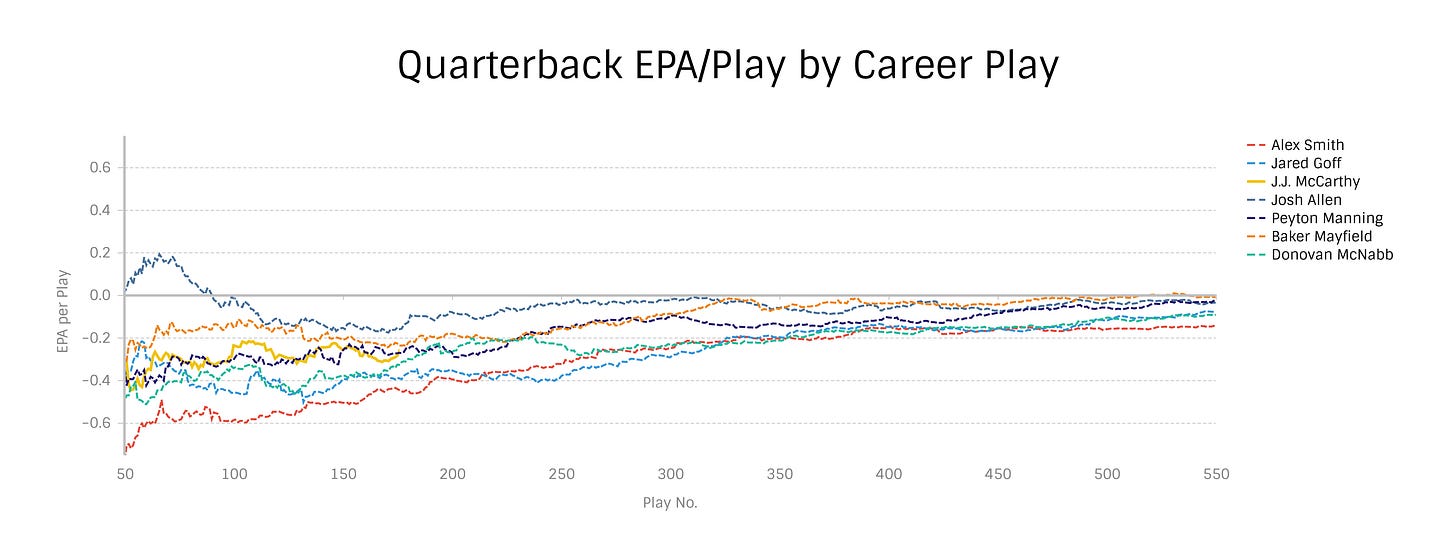

We know of a few quarterbacks who had a rough start to their careers. In fact, there’s one in the division; Jared Goff had a worse start than McCarthy did and is currently one of the best quarterbacks in the NFC. Josh Allen’s start was better, but he progressively got worse and ended up with a catastrophically bad rookie year.

We tend to focus on those two — as well as Peyton Manning — when discussing early-career dips before a turnaround into franchise quality. But a number of quarterbacks who have achieved “franchise” status have started out poorly.

Most have done better than McCarthy has through five games, but not meaningfully so. We can look at how their progress compares to McCarthy’s.

It would not be helpful if we only had one player to draw on when making these comparisons, but having a few to work with is nice. While none started quite as dramatically poor as McCarthy did, his improvements over five games were also more significant than theirs.

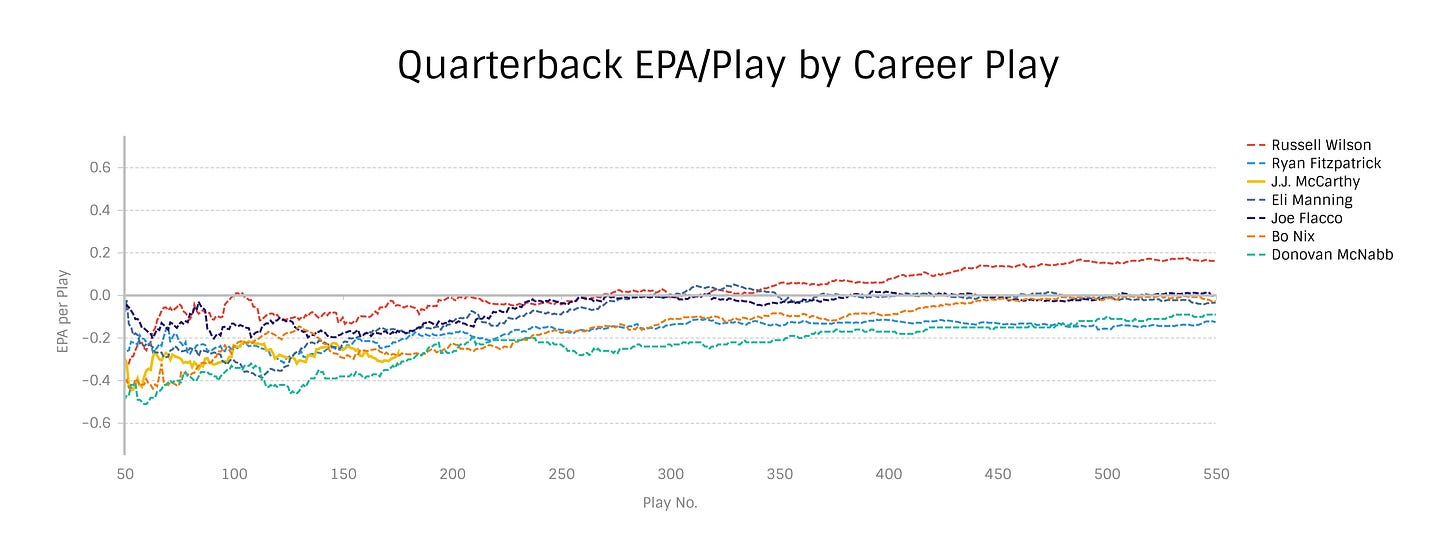

But looking at performance per dropback is a bit limiting, right? We’d miss out on the holistic contributions of players like Josh Allen, Lamar Jackson, Russell Wilson, Daniel Jones, Jayden Daniels and others.

And, like with Allen, it might be the case that as McCarthy’s skills as a thrower develop, he can contribute meaningfully with his legs.

So, let’s look at a chart that’s a little different after we use all offensive plays (designed runs and receptions included).

This isn’t the only set of interesting cohorts, for what it’s worth. There are more than a few franchise quarterbacks who have succeeded after an initial rough start.

One thing that seems to be clear from these charts is that by the time a quarterback hits around 350 plays, they should probably be meaningfully improving in their production in order for us to have confidence that they can turn things around and be excellent moving forward.

That’s no guarantee and improvement in production just might naturally be regression instead of pure development, but we see this much more often among long-term successes than we do among busts.

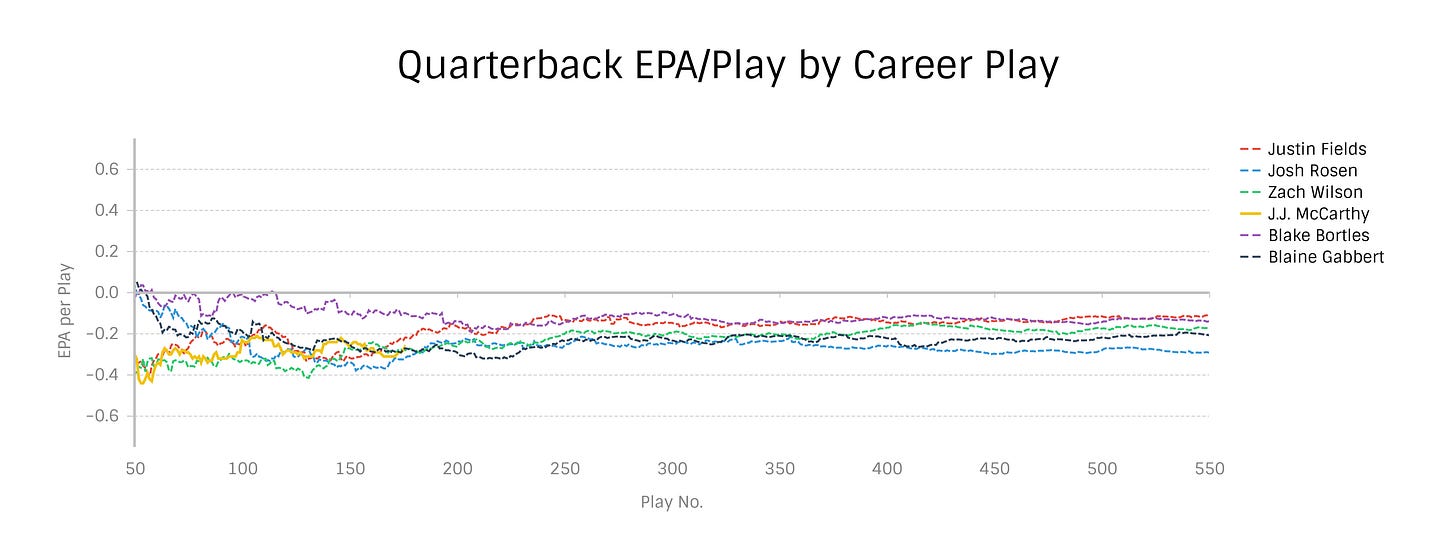

Here we see some notable busts who played poorly to begin their careers continue to struggle as the season goes on. Some did improve. Others did not.

This tells us that improvement is a necessary but not sufficient condition. If he doesn’t improve by the end of the season — he’s on pace for about 425 snaps by the end of the year — then it’s reasonable to have a discussion about what comes next. If he does, then there’s still some hope for the future.

Operations

There are other elements not captured in the production metrics worth discussing. Early in the season, the Vikings couldn’t get out of the huddle, perhaps because the normal calls in the huddle were overwhelming for McCarthy.

This problem led to the quarterback getting to the line of scrimmage with no time left on the clock, preventing the signal-caller from actually calling signals — no time means no ability to evaluate the defensive look and no chances to change the play. In addition to the obvious impact on the passing game, this inflexibility impacts the running game, which prevents the backs from generating good yardage against excellent run looks.

It also means the Vikings can’t execute elements like motions and shifts with the same smoothness; reducing pre-snap movement in the offense prevents McCarthy from seeing critical defensive cues and stops the Vikings from creating better matchups.

The most obvious element at play here has been the tremendous number of delay-of-game and false-start penalties. The Vikings currently lead the league in false starts per game with 2.0 and in all pre-snap process penalties (false start, delay of game, illegal motion, illegal shift, illegal formation, offensive offsides and too many men) per game and per snap with 2.9 per game and 5.05 percent of snaps.

When evaluating only plays when McCarthy is on the field, it looks worse — 3.2 per game and 5.95 percent of snaps. Though the Vikings had process penalties with Carson Wentz on the field, it was hardly the same degree of problem.

These are not the only process problems. Occasionally, offensive linemen won’t just hear the wrong snap count — they may hear the wrong play and set to an incorrect depth. Here, both tackles short set against the Baltimore Ravens despite a five-step drop from McCarthy.

Christian Darrisaw doesn’t “look” wrong here because the edge rusher to his side penetrates inside to make room for Taven Bryan to loop around, making a short set look fine. But Brian O’Neill is dealing with an outside speed rush and gets smoked — likely because he and McCarthy had different ideas of how far back the quarterback was supposed to drop.

Not only do we have evidence that the offensive linemen are hearing the wrong play, but we also have evidence that the running backs and receivers are hearing the wrong play. That’s why we saw running backs run to a different side than the one McCarthy was handing off to multiple times against the Lions.

On top of that, there are at least two instances in that game of players yelling “what’s the can” to J.J. McCarthy, meaning they needed to know what play he was audibling into when changing the play at the line of scrimmage.

These are communicated in the huddle — often, quarterbacks relay two plays: the play they intend to run and the play they will run if the first play doesn’t look good (if they “can” the play).

Tom Brady highlighted one instance that resulted in a false start.

That wasn’t the only play where a player needed to be told what the play was; earlier in the game, at about 7:11 left in the first quarter, tight end Ben Sims had to be told what the “can” was.

“I view those habits of the quarterback position as simple because the defense has no effect on that aspect of doing your job,” O’Connell told radio host Paul Allen in yesterday’s interview. “The hard part is the late, post-snap world of playing quarterback, where coverages and disguises and blitzes and things that they can control to make things much, much more difficult than breaking the huddle and knowing what to do and starting there.”

These are hidden inefficiencies that don’t always appear in traditional or even advanced production metrics. The quarterback is overwhelmed and the offense is dying in ways we can’t see.

The Many Technical Problems of J.J. McCarthy

So, we need a smoother operation and we need better production. What can be done to generate that?