Luke Braun's Film Room: Controlled Blazes — Why Sam Darnold Worked While Kirk Cousins and Caleb Williams Didn't

A fire-fascinated Luke Braun looks at the team debuts for Sam Darnold, Kirk Cousins and Caleb Williams, all mediated by different approaches to rebuilding and renewal. He, of course, looks at feet.

As is tradition around the start of the NFL season, California is engulfed in flames. As of this writing, there are 17 active major wildfires across the state including four surrounding Los Angeles County. These are a common occurrence around the months of September and October, when temperatures soar, dried-out brush can ignite, and desert winds carry the flames.

Of course, this is preventable with proper forest care. Cal Fire, the state’s authority on wildfire prevention and response, uses “prescribed fires” to burn out dead underbrush in a controlled way. That way, when it’s 120 degrees out and someone flicks a cigarette out their window, the surrounding 30,000 acres won’t ignite like a pile of sawdust.

Lately, thanks to climate change, summers have been drier than ever. Those conditions mean that Cal Fire can’t control these burns enough for them to be a safe option. They’ve had no choice but to let the forest overgrow into abundant wildfire food.

The key is targeted destruction. Cal Fire can effectively destroy what it has to destroy, but only if they can contain the blaze. If conditions are too damp, they burn nothing, and later wildfires get out of hand. But if conditions are too dry, they’ll burn more than what they intend to burn.

Only destroy what you mean to destroy.

When a quarterback assimilates to a new offense, coaches have to consider this same dynamic. How should the Atlanta Falcons adapt Kirk Cousins to Zac Robinson’s offense? How much should the Chicago Bears tinker with Caleb Williams’ electrifying game? What can the Minnesota Vikings do to keep Sam Darnold from torching their season?

In Week 1, we learned each team’s answers — and how well they worked out.

The Wrong Thing Burned Down In Atlanta

Kirk Cousins, a historically reliable 250-yard-per-game producer, was supposed to unlock fantasy football darlings like Kyle Pitts and Drake London. Instead, their offense sputtered to just ten points and -0.32 EPA/play. Cousins threw more interceptions than attempts beyond 20 yards. What happened to Minnesota’s Kohl’s Cash King?

When I caught up on the Atlanta game, I expected to see the same Kirk Cousins that I had covered for six years. I knew he had a bad game, and had seen plenty like it in Minnesota — even against a suffocating AFC North defense or a turnover-laden mess against a team nobody expected anything from.

I thought I knew what I was going to see. Instead, I saw a Twilight Zone oddity out of a parallel universe. I saw a deconstruction as damaging as anything that’s happened in Atlanta since William T. Sherman.

I saw Kirk Cousins in pistol.

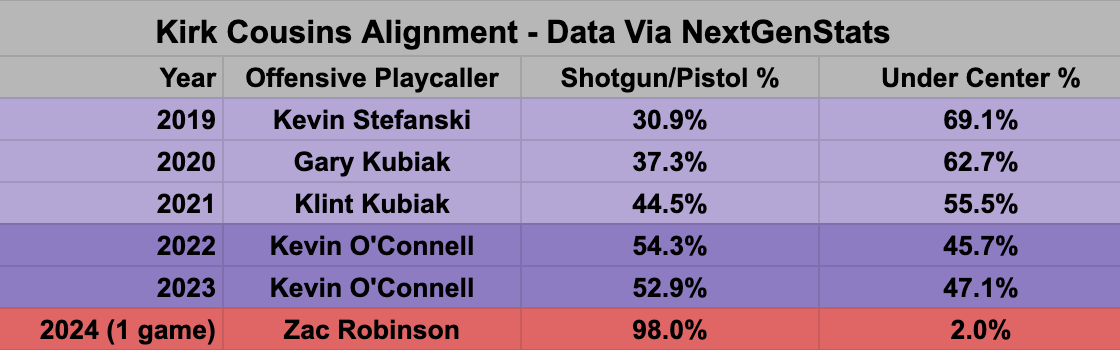

To understand how insane this is, you need to know Kirk’s history. Cousins is famous for his play under center, especially during the Mike Zimmer era. Offensive coordinators Kevin Stefanski, Gary Kubiak and failson Klint all used under-center formations as their main QB alignment.

Even Kevin O’Connell, a much more pass-happy playcaller, kept the ratio around 50-50 to set up play action and keep defenses on their heels.

Kirk Cousins is perhaps most famous for play action. He executes the run fake well and can throw on the run, and thus became something of a poster child for the Kubiak-style play-action offense that has the league wrapped around its finger.

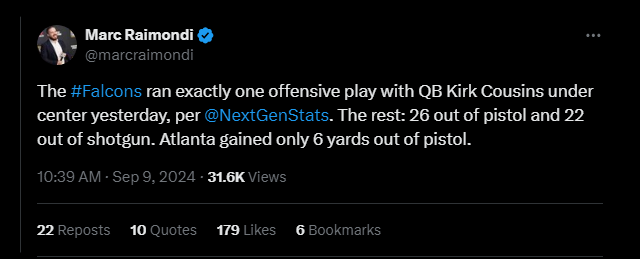

Atlanta had Kirk Cousins under center once in the entire game. They did not use play-action at all. Why spend $180 million on an established veteran QB if you aren’t going to let him use that foundation he’s established?

The Falcons might not have a choice. As you are well aware, Kirk Cousins suffered a ruptured Achilles less than a year ago. That is known to affect mobility and flexibility.

Perhaps the Falcons don’t want Cousins under center, where his dropbacks would be longer and place more stress on his injured heel. Not to mention the risk of an Ed Ingram-style incident.

The pistol is a creative solution if this is how head coach Raheem Morris and offensive coordinator Zac Robinson think about it. They can give Cousins a safe cushion behind the line but still give Bijan Robinson a head of steam when he does carry the ball. This doesn’t excuse Atlanta’s refusal to use play action, but it’s at least an understandable stab at solving a problem.

The real head-scratcher is with what Atlanta has done to Kirk Cousins’ feet. Cousins has, for his entire career dating all the way back to college, aligned with his left foot back.

Whether or not to align with your left foot back or your right foot back is a surprisingly controversial decision that each quarterback needs to make for himself. There are pros and cons to each, as well as with even (unstaggered) footwork, but the only important thing is to keep it consistent from play to play so as to not tip the defense off.

For Cousins, starting with his left foot back gave him a head start on his dropback. It cheated just a little bit of extra depth that helped him get to the top of his drop faster, and therefore get the ball out that much faster. He never had to have the fastest footwork because of this head start, and that helped his mechanics stay relaxed and consistent.

In his Falcons debut, Cousins used even alignment. The major advantage of even footwork is that it doesn’t commit your posture to the left or the right, which doesn’t require you to swing your front foot too far back if you have to hand off to that side. That’s not really an issue for NFL quarterbacks, however, or most college quarterbacks.

Here’s Caleb Williams, another left foot back QB, handling that with ease. More on him later, but for now just watch how he steps back with his right foot to give himself some room.

That’s a fairly basic building block of QB fundamentals. If Cousins is still so stiff that he can’t execute it, it would call into question the decision to play him at all. It has even impacted the effectiveness of the run game.

Whatever the reason, this was the plan. Kirk Cousins has been asked to change his pre-snap alignment for the first time in his pro career. And it’s clear that he is uncomfortable.

Here, he starts with his toes nicely aligned, but as he picks his right foot up to signal motion, he has to adjust his left foot. It goes back a little bit, like he is used to. At the snap, he steps back again. This habit will be really hard to break over time. It’s a small detail, but if Atlanta ever wants to work in play action, those extra steps will only get in the way.

The effects of strange alignment cascade here. At the start of his drop, he uses a “punch” step, which is that first little movement of his left foot. It’s just a rhythm and weight distribution step with no desire to get any depth — but Cousins isn’t used to it. It’s slower than it should be.

That gets him just a split second late to the top of his drop, and even though he gets the ball out of his hands as quickly as possible, he takes a major hit and almost throws an interception — lucky for him, and somewhat appropriately, Minkah Fitzpatrick loses his footing.

Couple this with Cousins’ already patented lack of pocket mobility and propensity for turnovers, and you get a very unique-looking disaster game. His mechanics have been razed to the ground in the interest of a cutting-edge fad.

And much like in 1863, the Reconstruction is backfiring.