Pushing Tush Is Ancient Technology

Somehow, Luke Braun has returned. He discusses the promethean roots of the Tush Push and how that history tells us how the play really works, not just how people imagine it.

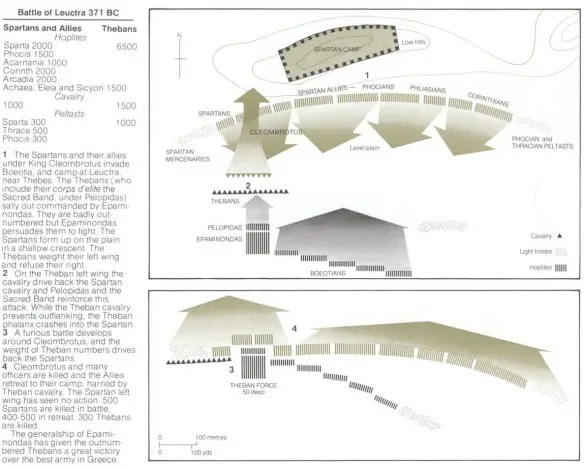

In 371 BCE, the Theban General Epaminondas did battle with Sparta at the height of its power. Sparta, having won the Peloponnesian War 33 years earlier, dominated Southern Greece and carried an invincible reputation. They were unstoppable, and they were coming. Thebes and the rest of the Boeotian city-states, led by Epaminondas, needed a way to fight back.

Epaminondas led a smaller force (some 6,000 to Sparta’s 11,000, though historians debate the exact numbers) to a field in front of a Boeotian village called Leuctra. The Battle of Leuctra would not only mark the beginning of centuries of Spartan decline, but also change the way Greek armies battled all the way through the conquests of Alexander the Great.

How did Epaminondas do it? How could he upend the mighty Spartan empire with a force barely half the size? The answer lay in resource allocation, patience, and 300 extremely important gay men.

If you had the misfortune of fighting against a Spartan army in the last few centuries BCE, you had to contend with a phalanx of hoplites. Thousands of men would align shoulder to shoulder, stick out their shields and spears, and push. You probably had a phalanx of your own, but against the Spartan line, you stood no chance.

Epaminondas didn’t have the numbers to directly contend with the Spartan phalanx, but he did have a specific elite force: the Sacred Band of Thebes. The Sacred Band was made of 300 hand-picked warriors paired off into homosexual couples. The idea was that lovers would fight more fiercely for each other.

Instead of a futile effort to out-push a force half their size, the Boeotians overloaded one side. They put a majority of their force on the left side, thinning out the right. They advanced this overloaded left wing before the weaker right wing, hoping to win before the Spartans could fully engage.

The Boeotian left wing, led in part by the Sacred Band, broke through the Spartan line. With enemy forces charging the side and rear, the Spartans quickly routed. When the dust settled, Epaminondas inflicted upon the Spartans one of the most decisive blowouts in Greek history.

Over 1,000 Spartans perished in the Battle of Leuctra, including their king and military leader Cleombrotus. The Boetians lost around a hundred, but exact estimates are hard to come by. By anyone’s estimate, their casualties paled in comparison. Sparta’s military reputation would never recover, and the next 200 years marked an era of Spartan decline.

Epaminondas didn’t invent the phalanx. In fact, it’s unclear who really did. There is evidence of a similar strategy in Sumer over 2,000 years earlier. It’s a fairly basic idea — everyone hold your shields together and push. But Epaminondas did advance the strategy. Others would continue to innovate on Epaminondas’ “oblique” advance, up to and including Alexander the Great.

In modern day, we still hold the sacred tradition of lining up a bunch of guys and having them push against each other. We’ve replaced shields and spears with helmets and pads. Instead of the famously unstoppable line of ancient Sparta, we have the Philadelphia Eagles.

The History of the QB Sneak

On Thursday night against the Giants, the Eagles ran their vaunted “Tush Push” four straight times for a touchdown. It frustrated the nation and even the Eagles’ direct rivals.

Oh, but it is, Micah. It was football before the game morphed into what we recognize now. It was football as your great, great grandparents would have seen it. Back when there was a 20-yard limit to a forward pass. Before there were downs or end zones. Over 120 years ago, football looked like this:

Video of Yale vs. Princeton, 1903, courtesy of the Library of Congress

Does anything look familiar?

The key difference in this archaic footage is that the snap goes directly to a deeper running back, rather than a player under center. That part is admittedly more modern — popularized as the T Formation by George Halas’ Chicago Bears around the end of the Second World War.

The T formation itself had been around for decades, but as the newly legalized forward pass gained popularity, Halas and his staff transformed it from a gadget play into a mainstay.

From The Genius Of Desperation by Doug Farrar, p4:

“Named this because there are three running backs behind the quarterback in the shape of a T, the formation allowed the quarterback to drop back to pass, give different rushing options, and offered new sleights of hand”.

After a game-long slog of trying to get through seven burly blockers and then decode who had the ball, it could be effective to eschew the handoff entirely, push everyone forward and rush with the quarterback.

Sid Luckman even scored on a QB sneak in the greatest blowout in the history of the league, Halas’s infamous 73-0 championship win. This kind of play dominated football at all levels. Move the man across from you, run the ball, and maybe add a wrinkle like a pulling lineman or counter step.

Decades later, the 1967 Ice Bowl between both of Parsons’ teams, the Packers and Cowboys, was decided on a QB sneak. In 1982, Joe Montana snuck the ball into the end zone to start the scoring in Super Bowl XVI. QB sneaks have been a front-facing part of football for longer than helmets.

Football has evolved beyond the T formation, but these plays, as we see them, harken back to the prehistoric age. Like a 265-million-year-old species of alligator in a municipal zoo, an anachronistic beast surrounded by a softened modern world. So we endeavor to keep it caged.

The Tush Push itself, however, is distinct from these classic QB sneaks. It is defined by its namesake, the push of the tush. The Eagles have two players line up behind Jalen Hurts and push the pile. Pushing players from behind has only been legal since 2005, making it a comparatively new innovation. So what’s so offensive about it 20 years after the rule change?

What’s Wrong With The Tush Push?

There are two major critiques of Philadelphia’s Tush Push. One is about safety, the other is about competitive fairness. Neither reason proved sufficient for the league to ban it when prompted in the 2025 offseason, though the vote was close and could be re-tried in the future. So it’s worth considering the proposal’s premises.

First, the issue of safety. The world is rightfully laser-focused on concussions and other dangerous injuries in one of the last remaining truly barbaric modern sports. Surely a play that requires Jalen Hurts to lower his head and then smush himself between the entirety of both teams is dangerous, right?

Perhaps not. In February, an internal investigation found no injuries as a result of the play, either by Philadelphia or any other team. I should note that Chris Jones sustained a neck injury in the Super Bowl after this play, where he lined up sideways, but returned to the game. This appears to have been dismissed by the NFL’s investigation.