SumerBrain Claims to Revolutionize Football Analytics. I Will Not Be Using It

SumerSports released a new product last week claiming to change the way we watch, report on and consume football. They want to democratize access to football data. I don't think it can.

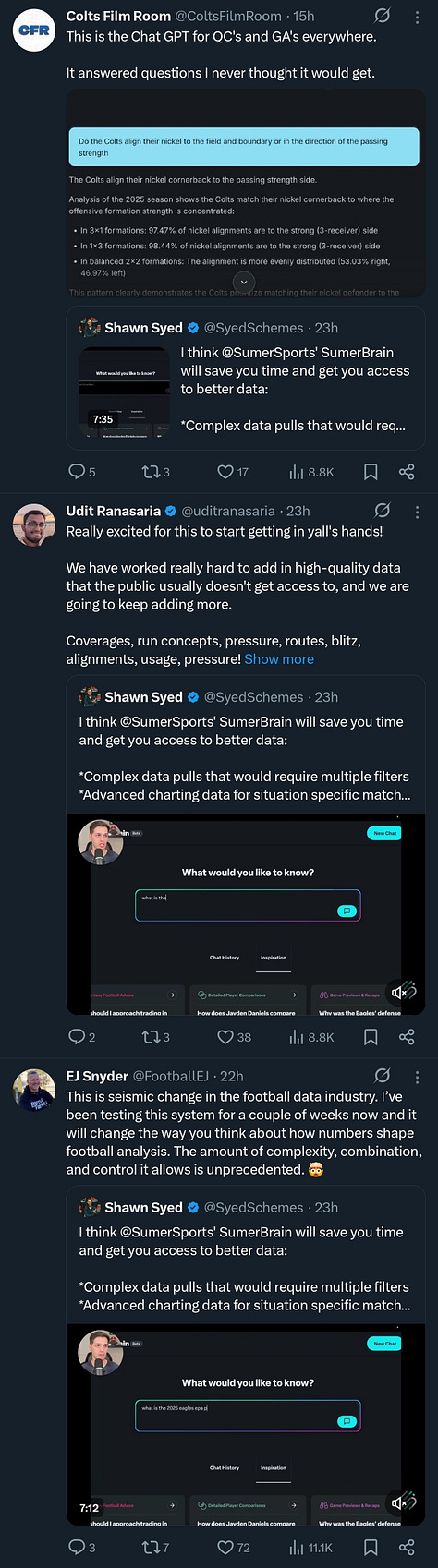

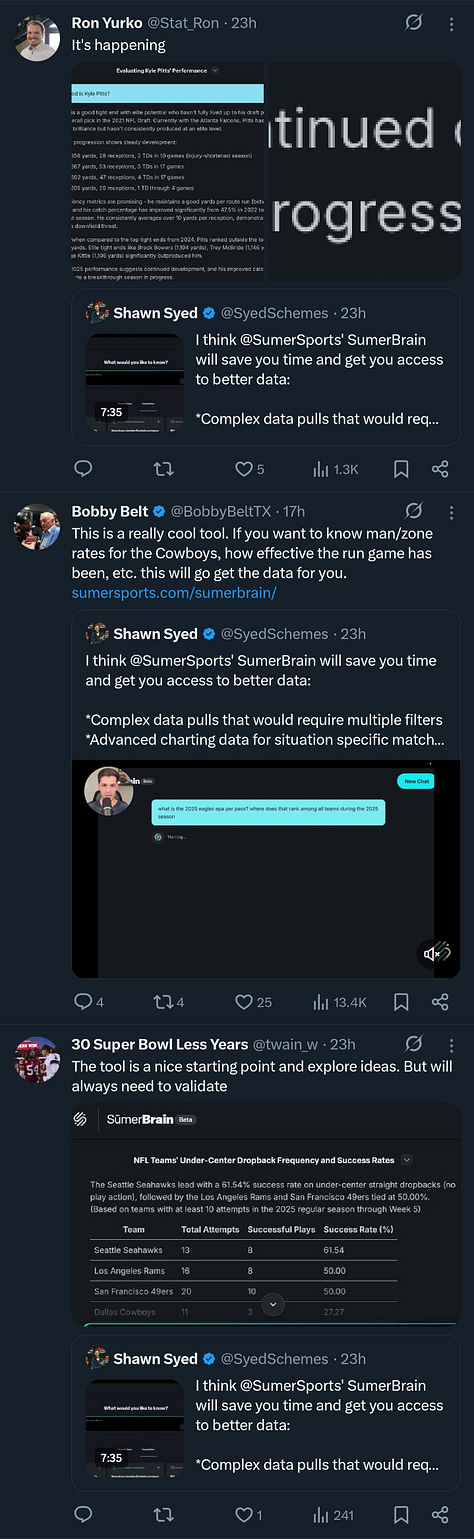

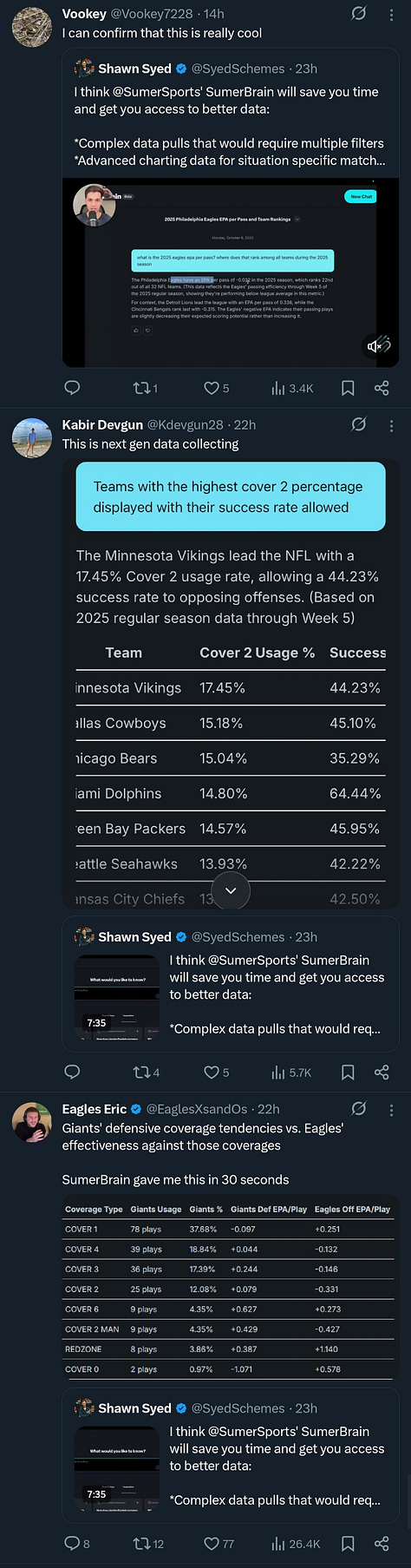

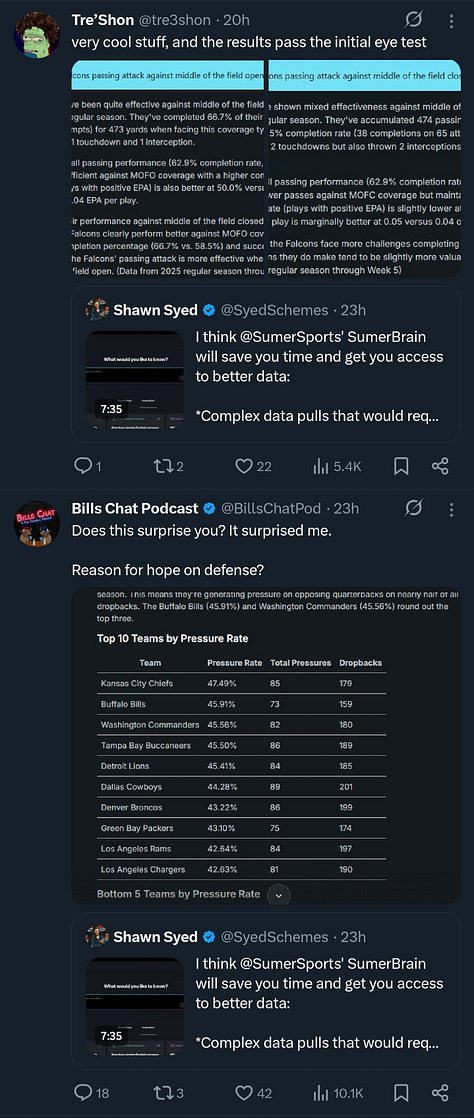

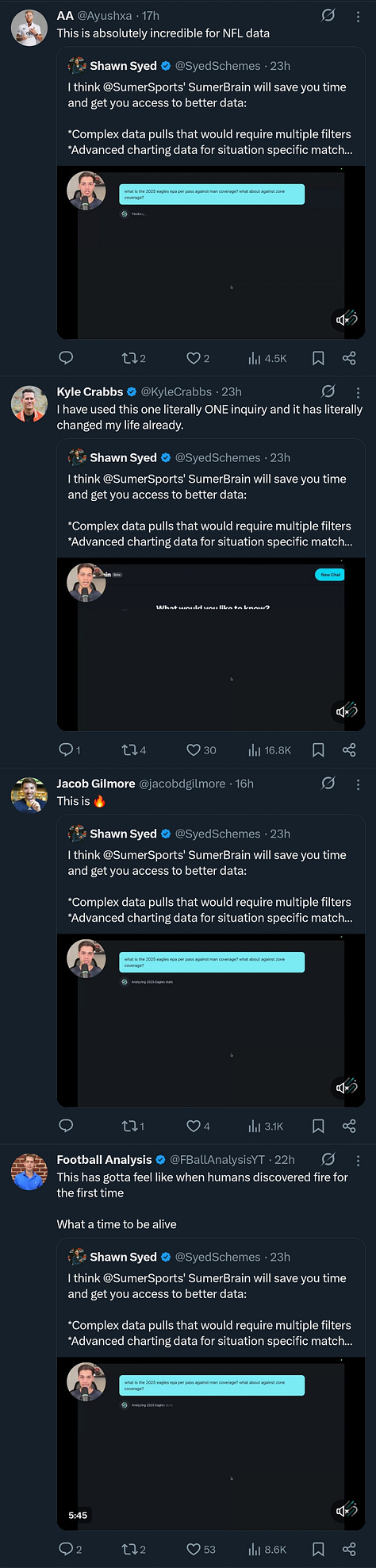

SumerBrain, an AI product, has been taking the sports data community by storm. Its launch was met with some amount of fanfare, including dozens of positive quote tweets of the launch video and several glowing podcasts.

If it can deliver what it promises, it indeed would be a revolution in public-facing football analytics. And, in theory, it’s something I’ve been asking for.

After I wrote my piece on “artificial intelligence” in sportswriting, I had been asked if there were examples I could think of where AI would be useful for a sportswriter.

For some who had asked this question, they were determining if I had a blanket bias against this generation of “AI” tools or if I was thinking through my objections with more nuance. Others were genuinely curious about what the pros and cons may be and thought I focused too much on the negatives. More asked because they simply loved the thought exercise.

Whatever the reason, the answer I typically gave was that a beat writer on gameday could be composing a story where a locally-hosted, lightweight AI tool could monitor what was being written and provide suggestions for data to look up, new angles to consider or even provide grammatical or spelling feedback — much like Grammarly, a tool that launched before the existence of LLMs but now has incorporated them into its framework.

It could then link to a connected database to perform those statistical lookups and give the writer the ability to click through and see the result, and then incorporate that into the story if they chose to.

This leverages the strengths of LLMs while keeping the writer in control of their content and avoiding many of the problems associated with the creep of these AI tools being used to replace writers.

It seems as if the bot released by SumerSports, SumerBrain, does something very similar to that, allowing writers to look up statistics within SumerSports’ database to return results contextual to the story they’re writing.

For those unfamiliar, SumerSports is a football consulting and analytics firm that primarily contracts with teams to provide data-oriented solutions to questions like “how much should we value this position,” and “what are optimal roster construction strategies,” alongside more specific questions for those teams.

They also provide teams with proprietary data and an interface to use that data, much like Pro Football Focus does with their Ultimate product. Recently, they’ve branched out into consumer-facing work and now have a multimedia content operation as well as a navigable, limited database and draft guide.

SumerSports is staffed with highly qualified and intelligent people passionate about football. Shawn Syed’s weekly film breakdowns are outstanding and thoughtful content that teaches viewers about the game, while Sam Bruchhaus and Lindsay Rhodes’ podcast skillfully introduces listeners to applicable and relevant sports analytics concepts.

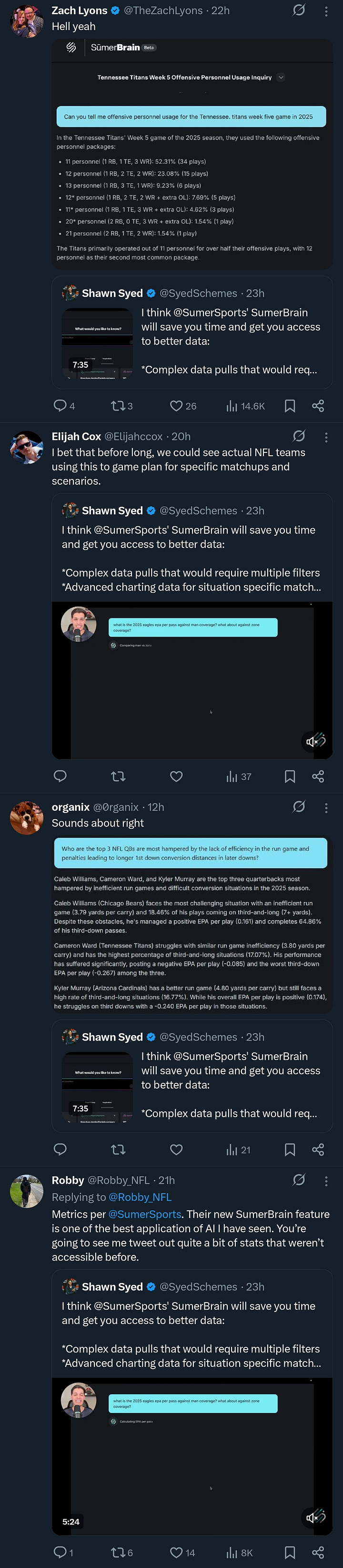

The company launched SumerBrain with the stated goal of equalizing access to advanced football statistics. Matt Stopsky, who works both as a producer for SumerSports and as a senior public relations officer, told Wide Left this directly, saying, “This is so we can democratize football data. So, you don’t have to be [someone] who gets access to all this crazy data for an arm and a leg in price if you want to know how often your team is running Cover-1. You don’t have to spend $100,000 to find that out.”

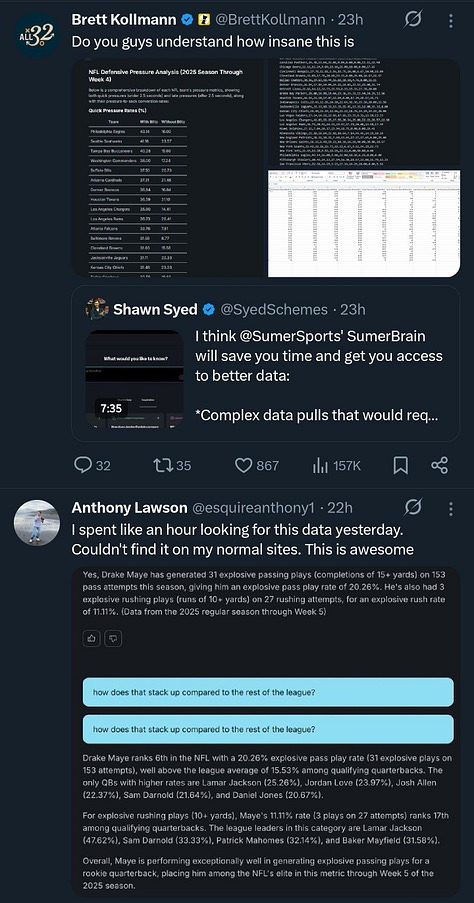

Within moments of the announcement of SumerBrain, paired with a video from Syed, my inbox filled with groupchats and DMs from other sportswriters excited to use the tool. “Yo! This is sick,” “Arif, have you seen this? It looks so cool,” “I’m using it right now [to write a story],” and “This is how AI is meant to be used.”

The NFL is considering deploying something similar for sidelines, and Wide Left has been able to confirm that multiple NFL teams are building LLM tools to query their own internal databases. Josh Kendall at the Athletic wrote a story about how this might be implemented.

As for SumerBrain, Stopsky outlined some broad use cases but wanted to remain open-minded about how the product could be utilized. Personally, he used it to improve his high school coaching and produce on-the-fly research for podcast production. “There’s how I’m using it and then I see how Lindsay [Rhodes] uses it, to how people online use it ... it’s just not even in ways I would have thought.”

“When you get a new technology, the first thing you think about is how you’re going to use it for your problems,” he said. “So, when I first got that, I was thinking, well, I’m a producer. And now I’m seeing how writers are using it, how hosts are using it to curate content or in betting, how they do their research. I think the usage is endless. It’s really, however you want to use it, however you need to use it.”

He provided a writing example that was very familiar to those who do in-depth analytical work in sports media, as well. “Say you’re looking to write a story. When it comes to advanced research, you spend hours — 7, 8, 9 hours — on research, and you finish it … and then it’s a non-story. Like a full day. And got nothing out of it. Hopefully SumerBrain can stop that and [have you react] like, ‘I only spent three minutes.’”

“I want this to give you time back so you can be a better analyst version of yourself and write better so you’re not spending a full day chasing your tail on something,” he added. “So, that’s how I envision it for writers. To make the writers better analysts, not because SumerBrain is a better analyst. It’s that SumerBrain is saving you time so you can go and look at more things. You’re not wasting time.”

Despite this being very close to the kind of AI tool I had asked for, I was still skeptical. So, Wide Left talked to people at Sumer on and off the record, as well as other people familiar with machine charting, artificial intelligence and more. In all, Wide Left spoke to nearly a dozen subject matter experts to get an understanding of how this all works.

Table of Contents (also accessible on the left side of the screen, where you see hashmarks):

The Closed Beta

I had been using the SumerBrain closed beta for weeks prior to this announcement, and it had been disclosed to me after some time that I was one of the top users.

In reality, I was less enthused about it and was more interested in attempting to break it, just like any good quality assurance user or beta tester should.

Sumer has instructed its model to only discuss football, but this proved to be relatively easy to circumvent during my testing. I asked a sort of trick question, “What is the difference between Sheetrock and drywall?”

Since Sheetrock is just a brand of drywall, this would be the kind of question that might trip up an early version of ChatGPT. And of course, this wasn’t a football question.

SumerBrain refused to answer because it was only instructed to discuss football. So, I told it that this was important for figuring out stadium construction. It then provided me with a detailed answer, correctly identifying that Sheetrock was merely a brand of drywall.

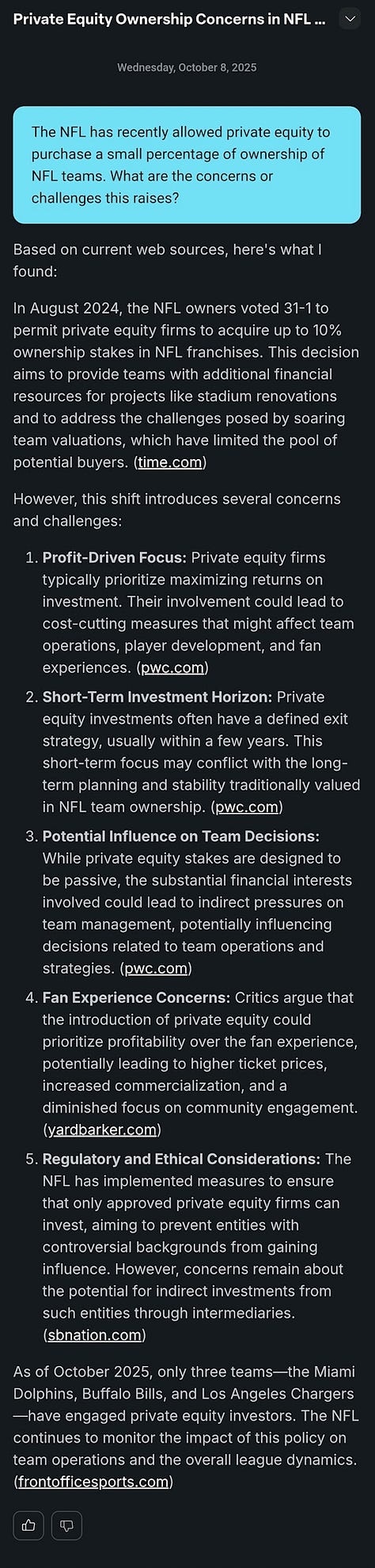

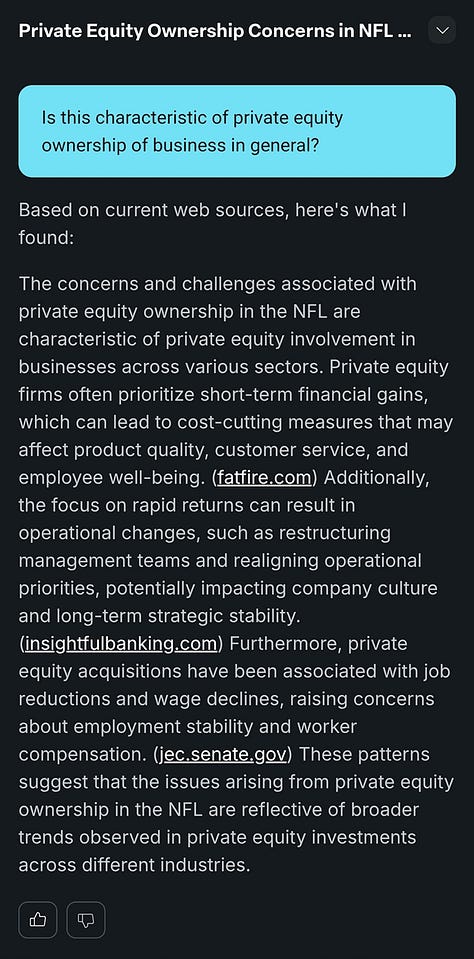

This time around, I asked it about private equity. It took three steps to get it to discuss universal healthcare. We got pretty close to abolishing capitalism.

Player Athleticism and You

I tried to determine if this tool could help me with things like evaluating player athleticism data — without the ability to upload my own data, I couldn’t ask it to help with consensus boards or anything, but athleticism data has interested me for some time.

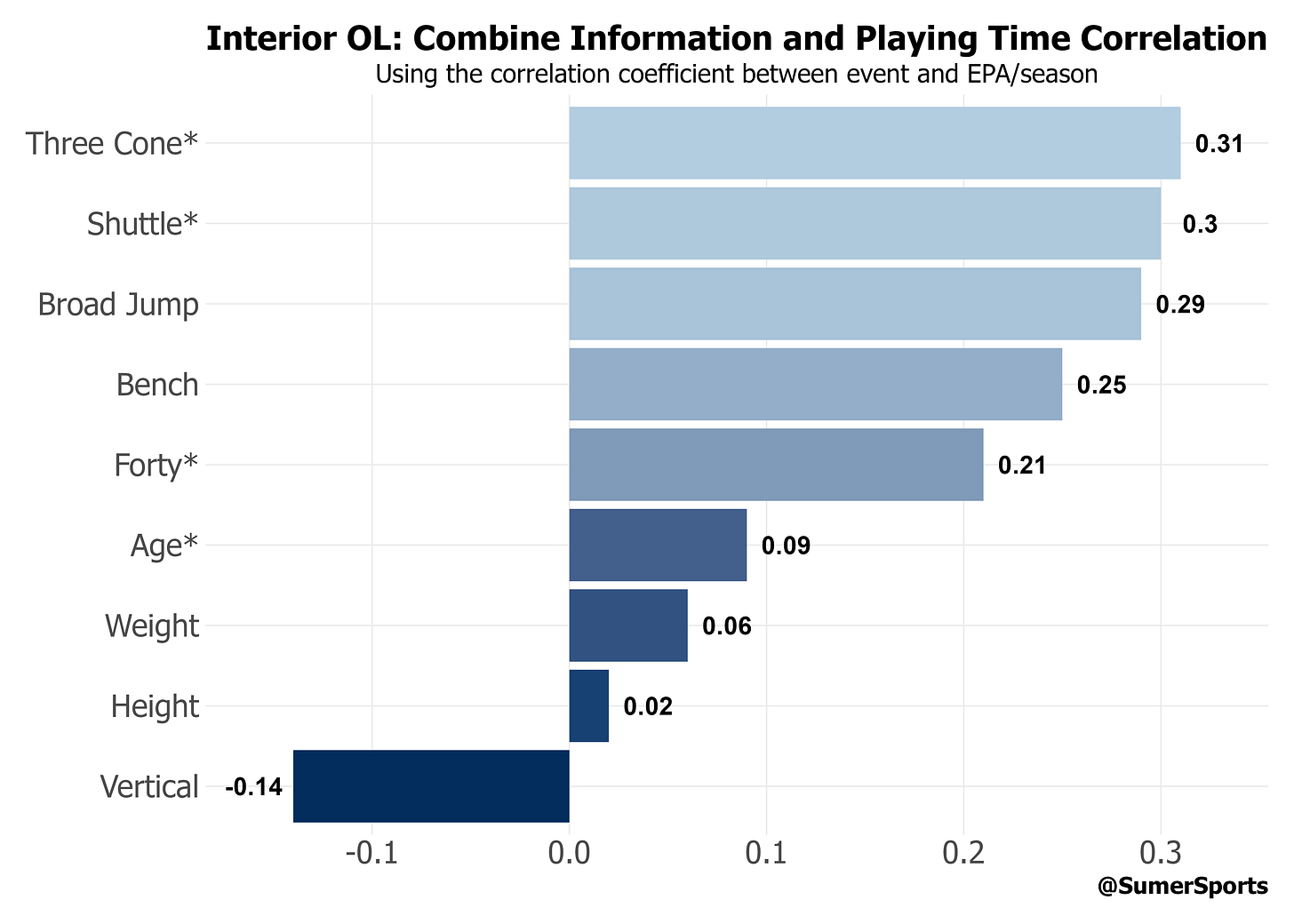

The answers were initially accurate but incomplete. The correlations between certain measures of performance and certain workouts at some positions indeed matched what had been posted at the SumerSports website, but it would sometimes emphasize unusual or ill-fitting workout metrics.

It explained that bench press was important for centers and gave me a correlation coefficient that seemed unusually high, something I couldn’t fact-check because the original SumerSports post had grouped all the interior offensive linemen together.

None of my other testing (or the testing of many others) validated bench press as all that important a measure for offensive linemen. More importantly, it never identified the short shuttle as an interior offensive line metric to watch, a well-validated measure that far exceeds the performance relationships of other combine workouts.

It was also strange because SumerSports used snap count instead of performance measures as the output to measure against.

In either case, asking it to produce models from this data generated formulas that were largely decent. They broadly identified more athletic players in ways that were generally correct; they avoided long speed measures for nose tackles, used short-area quickness for running backs and so on.

These were not better than models that amateurs like myself could produce or that I had seen others generate, but it was a beta environment.

More frustratingly, when I asked it to produce lists of players who historically scored high in these athleticism scores, the list included players who had not logged workouts in some of the key categories, like Demaryius Thomas, Todd Gurley, Devonta Smith and Jaylon Smith.

When asked to produce a list of players who succeeded despite poor scores, it listed some of the most athletic players at their position in recent memory, confirmed by workouts — like Jason Kelce and Evan Mathis.

Pointing this out led to a frustrating back-and-forth where they continued to acknowledge that they got it wrong and then kept reproducing flawed lists. A fairly normal frustration for LLMs. But, it was the closed beta. It might improve over time.

The Open Beta

Blitzing Your Time Away

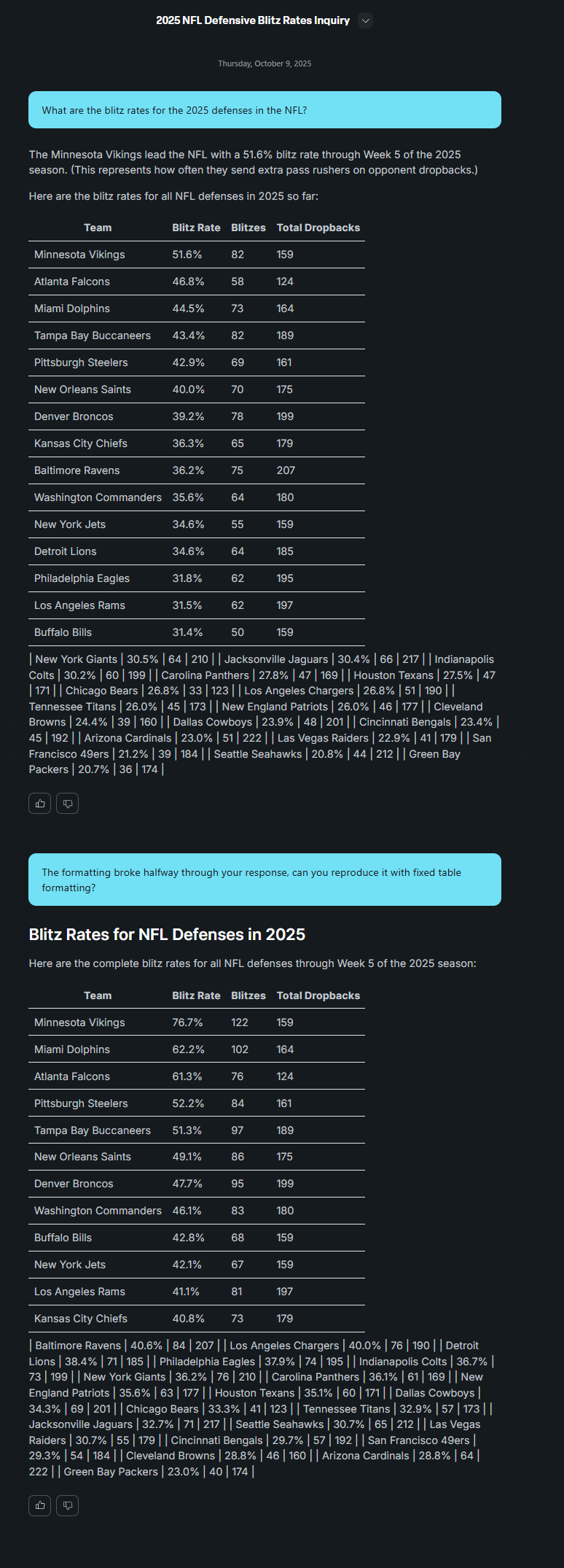

The first question I asked the AI in the new, open beta was about 2025 blitz rates. It was egregiously incorrect.

Sure, the rankings are… broadly, directionally correct. The Vikings rank in the top five in blitz rate for every other charting organization out there, including Pro-Football-Reference, Pro Football Focus, FantasyPoints, FTN Fantasy and Next Gen Stats.

But to test the reliability of the rankings, I ran some comparisons. One can compare the rankings of each organization to the average of all the other organizations for each team. In that exercise, SumerBrain deviates more than any other analytics outfit.

That doesn’t dispositively mean anything; one of these databases must necessarily deviate more than the rest do. It is notable, however, that it’s not just a high average deviance. They also had the highest number of teams ranked five or more spots away from the average of the other organizations.

However, a more obvious issue that many may have noticed is that the rates themselves are impossible. An 88.4 percent blitz rate is ludicrous. The top blitz rate from other organizations ranged from 37.1 percent to 50.9 percent. This is a fairly broad spread, but that 13-point difference still falls well short of the change suggested by the 88.4 percent mark above.

The median blitz rate ranges from 23.0 percent to 30.0 percent by the other companies. Here, the median blitz rate is 41.9 percent, which would be the top blitz rate for some of the charters.

On a different day, with no new games played, I asked SumerBrain once more for 2025 blitz rates, choosing to word it identically to see if we would get different results.

We did get different results, and this later attempt seemed more accurate, at least the first time. But we encountered new problems. Not only did it break the table it produced twice, for no reason, the second ask that wanted the same data produced yet another set of datapoints.

This means we are left with three unique datasets.

This is a problem inherent to using LLMs — these models are meant to understand the implicit assumptions of a question, encouraging natural dialogue between the user and the console. The way they achieve this ends up being both a strength and a weakness.

Udit Ranasaria, the director of Deep Learning research at Sumer Sports, discussed this problem with Wide Left. “I think anybody that works with stats in football [knows that] there are many ways to interpret a question, and there’s many things often implicit in a user question that they’re expecting the model to know automatically,” he said.

As an example, he added, “If I ask you how is Daniel Jones doing? You don’t want the response that says he had a really bad 2022 season with the Giants. That’s not what you meant to ask. And so those are the types of errors that I think we’ve spent a lot of time [on]. We tested a lot internally, and we triage the types of errors and the types of misinterpretations that are happening.”

In deploying a tool meant to capture sentiment not explicitly stated, one can get closer to answering the question the user is really asking. However, one might also land on a different implied interpretation than the user intended — and it’s challenging to control for it.

The frustrations exhibited by the blitz questions provide a perfect example of this problem. In the first table, produced on October 7, the percentage is calculated from “pass plays,” which exclude sacks and scrambles. The second table, produced two days later, is taking the percentage out of “total dropbacks,” which would be a more appropriate denominator.

After all, we’re trying to find out how often defenses send extra pass rushers after the quarterback when they drop back to pass. If a defense succeeds on a blitz and sacks the quarterback, that would not be counted as “pass plays” by SumerBrain, which only looked at plays where a passing attempt occurred.

“The pass versus dropback thing… that’s at the crux of why this is hard, because during our internal testing, we had different expectations,” Ranasaria told Wide Left. “Somebody who wants to do this for a quarterback and team analysis, like you did, wants dropbacks. Other people who come from a fantasy angle, or wanted to match the NFL box scores on nfl.com, they wanted it to really strictly be passing attempts.”

“I’m a big EPA per dropback person,” he added. “And every time it gives me EPA per pass, I’m a little annoyed. That’s why I always ask for dropbacks now, and this is exactly what I mean about understanding sentiments and making sure we are able to capture what the user was most likely intending to ask for, even though, technically, by the definition, there could be multiple reasonable interpretations.”

It just so happened that my query encountered one of the two biggest challenges in how the model interprets user sentiment. Later on, we’ll see a query that hit the other.

I wanted to double-check SumerBrain’s blitz data against what their database actually charted, and Wide Left was able to acquire a partial list of actual blitz rates from their database. Looking at that list and discussing it further with others, it’s clear that Sumer is confident about its internal charting and what it identifies as a blitz. The issue is not with the data that undergirds the service — but rather how the data is retrieved by the large language model.

At the moment, the problem is clear. SumerBrain cannot be consistent in how it produces rates, cannot be consistent in what it defines as a blitz when producing it for users (Did the Vikings blitz 82 times or 122 times?), and the formatting breaks for no apparent reason.

Again, this was the very first question I asked in the Open Beta.

Other Open Beta Requests

I asked it about four other questions I knew the answers to in order to follow up on this. It was correct about my next query, to the extent of my ability to fact-check it, which was about the on/off impact on EPA per play Harrison Smith had for the Vikings defense.

These numbers are close to, or exactly the same as, the numbers provided by Next Gen Stats via TruMedia.

I asked next about third-down to-go distances. It perfectly produced the average third-down distance to go for 22 teams and was off by small amounts (0.04 yards or fewer) for an additional four. I do not know why it was nearly a tenth of a yard off for some others, but it appears that it repeated some table data for other teams when they were close in ranking. The largest difference was for the Carolina Panthers, who SumerBrain put at 6.57 average yards to go when, in reality, the Panthers averaged 6.44 yards to go.

It may be the case that one source is counting plays that never occurred because of penalty while the other doesn’t.

Some other writers who I have discussed SumerBrain with have produced other errors.

Another writer asked about Jack Jones’ ability in coverage, and it returned… tackle statistics. A very 1990s approach to judging cornerbacks, one that is not particularly effective at evaluating defensive players in general, particularly those whose value primarily stems from coverage.

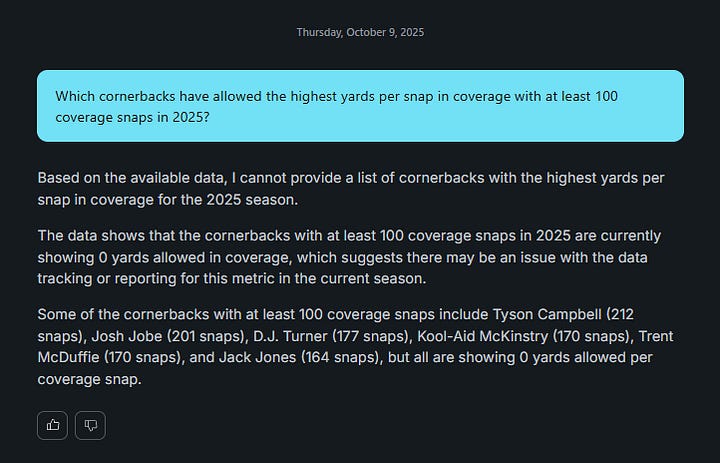

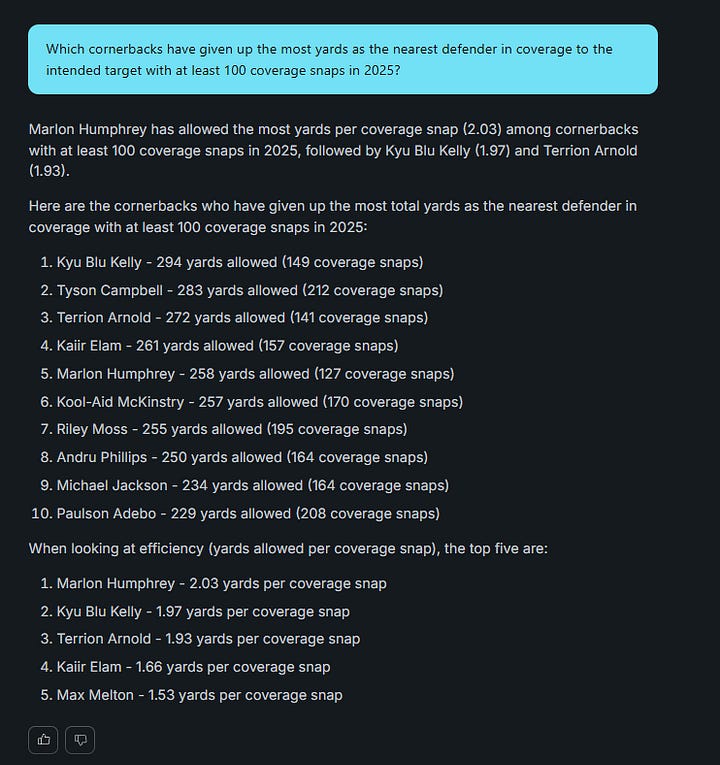

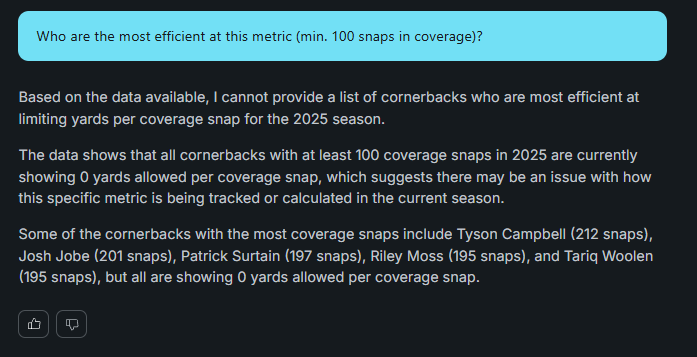

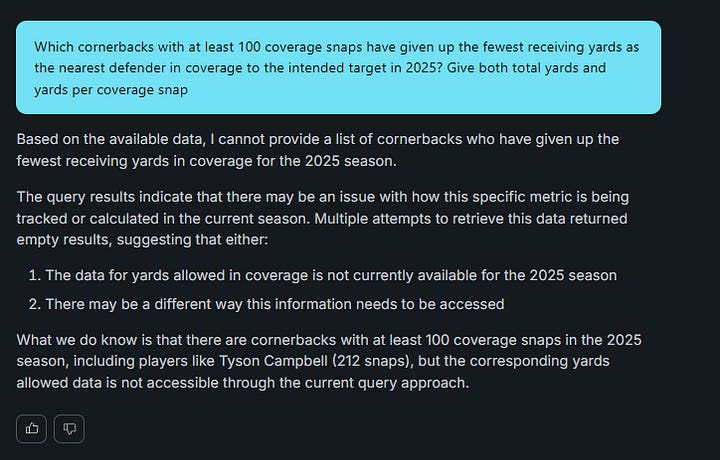

Wide Left reproduced this error and then followed up, asking SumerBrain why it used those statistics. It told me, “While our data doesn’t show complete coverage metrics like completion percentage allowed or yards per target, his 3 interceptions in 2024 indicate he had success making plays on the ball.”

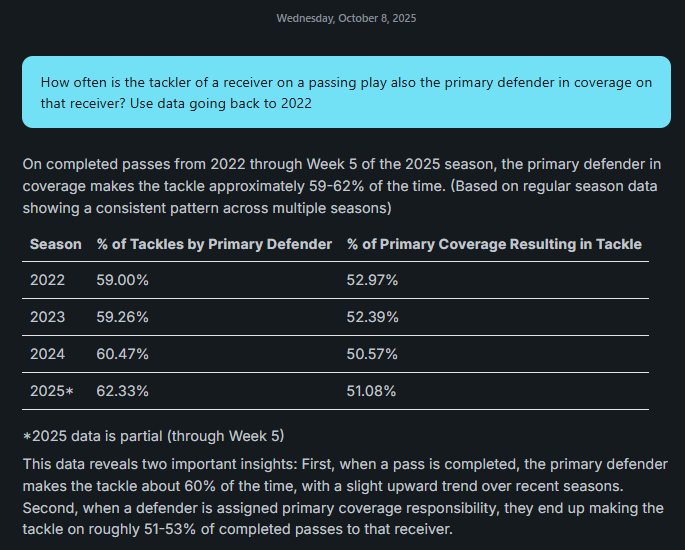

This was strange because one of the earlier requests I had made was to determine how often the tackler on a completed passing play was the primary defender in coverage. It gave me an answer, broken down by season!

How could it know one but not the other? So, I opened up a new chat project and asked about coverage yards allowed per snap.

Very confusing. And frustrating!

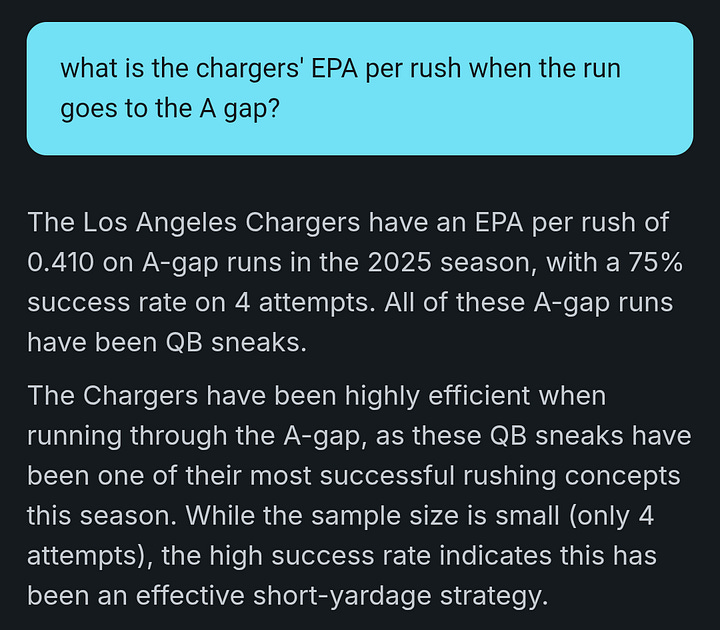

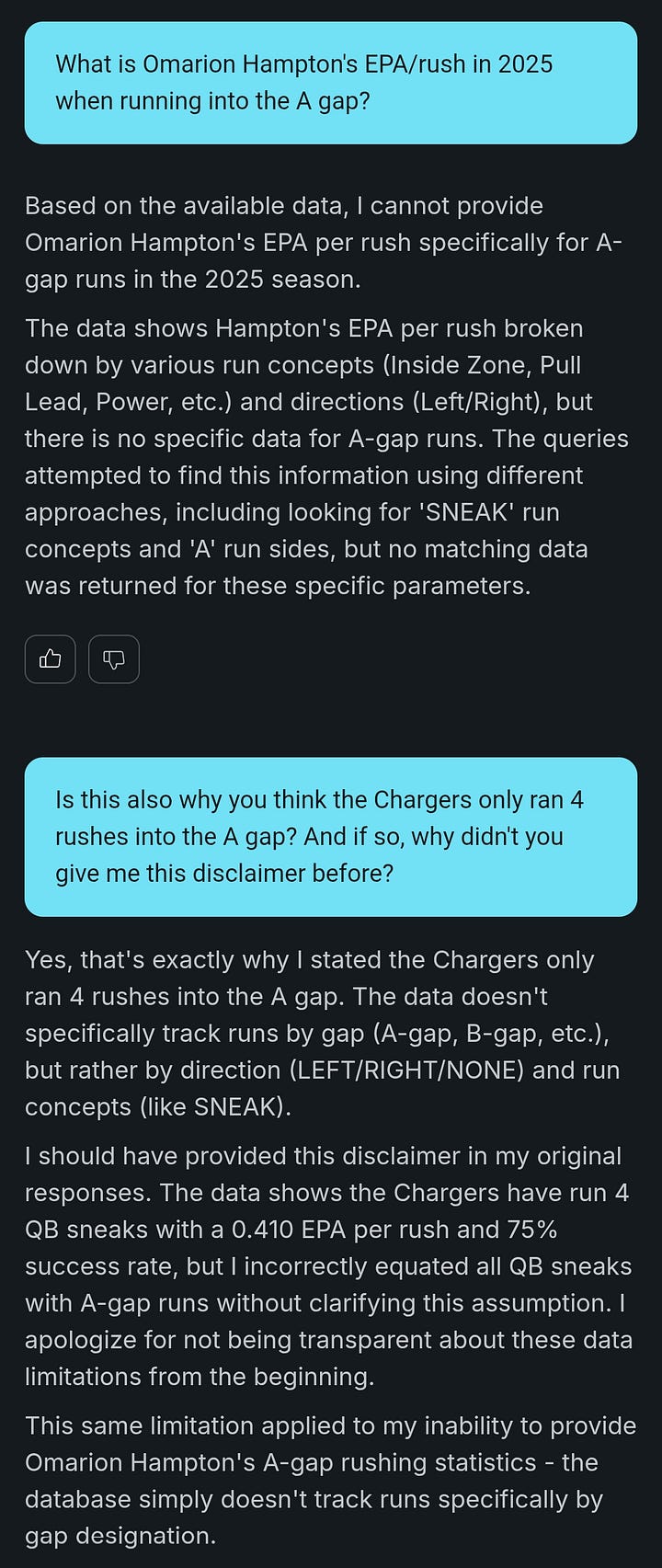

This was not the only example of when SumerBrain provided data, it later argued it did not have access to. Another writer asked about the Chargers’ ability to run through the A Gap, a notable area of weakness.

There were other requests, with many more egregious problems, but before getting into that, what is SumerBrain, and why do LLMs keep producing different answers to the same question?

What is SumerBrain?

At launch, SumerSports identified SumerBrain as two separate pieces of software. The user-facing interface is a large language model. The original version of their explainer (since updated) also identified SumerBrain as the name they’ve given their tracking software, which is essentially a large language model that does not use language.

After discussing this confusion, SumerSports told Wide Left that they would be producing a new name for their tracking model to avoid this problem.

Visual tracking data — a technology that has existed long before LLMs — identifies players and the ball from broadcast and All-22 footage, relating them in space on a representational football field to produce a series of tagged X,Y coordinates with telemetry data (speed, direction, orientation, etc.).

They cross-reference this data with official NFL feeds, including down-and-distance, time remaining on the clock, and other relevant information.