The Brian Flores Defense: A Comprehensive Guide, Part 1

Luke Braun begins the process of constructing his almanac for the Brian Flores defense. He starts by discussing one of the most influential tacticians in the world of chess.

“I do not play chess – I fight at chess.”

In 1921, legendary chess grandmaster Alexander Alekhine played Endre Steiner in a tournament in Budapest. Steiner, playing white, started with the standard 1.e4 - the most popular opening move in the game. Alekhine responded with something bizarre and unorthodox.

He moved his knight out first. In most games, this happens eventually, but is inadvisable straight away. Most chess openings set up some defenses before placing their knight in striking range of an opposing pawn. Here, that lonely knight was nothing more than a target.

Steiner pounced, pushing his pawn forward and attacking that knight. That forced Alekhine to move his knight twice in the first two moves, a dreadfully inefficient start. In chess, you want to get as many pieces out as quickly as you can. Two crucial moves on the same piece is far from ideal.

But it was worth it. Alekhine was willing to accept that cost to get Steiner to over-extend his central pawns.

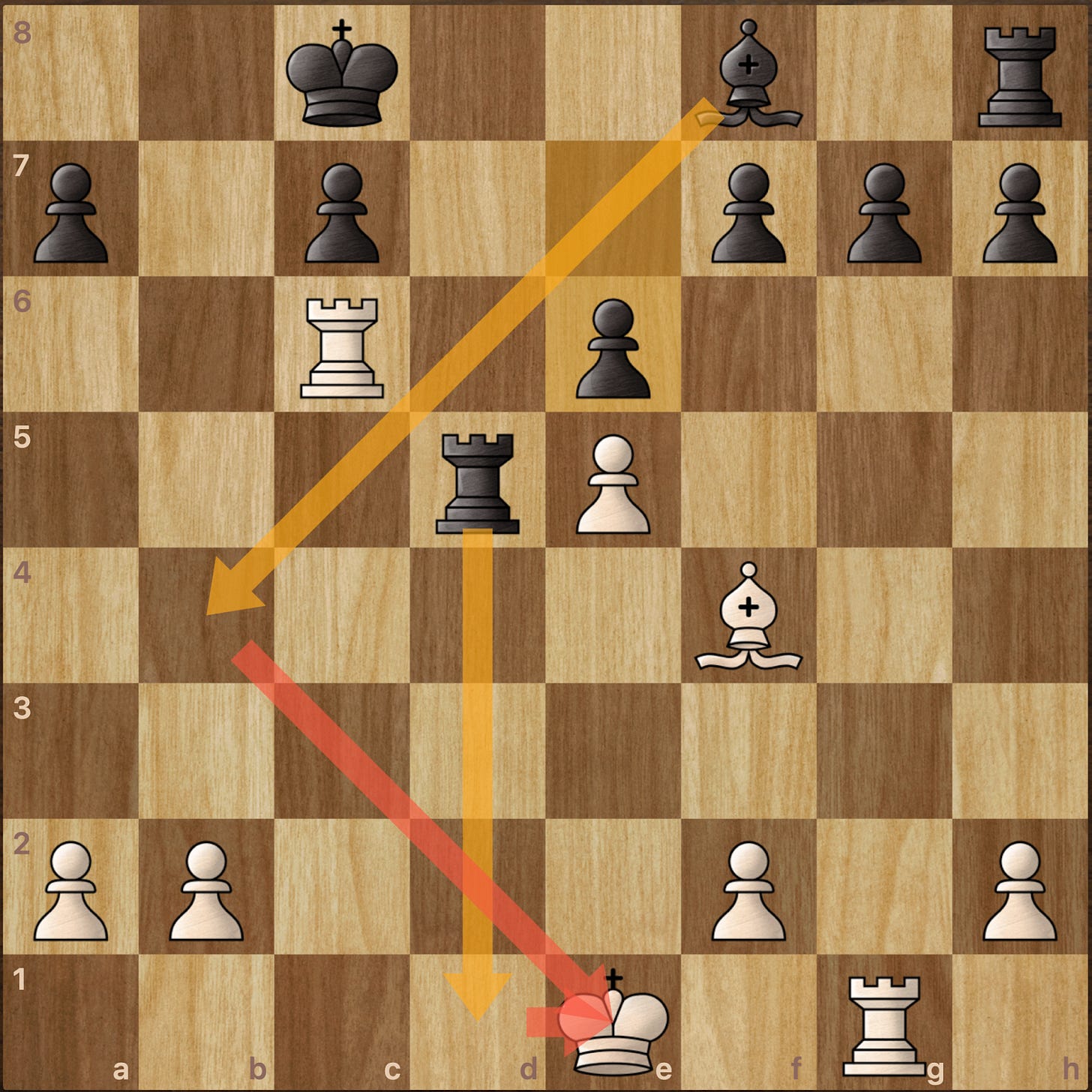

Fifteen moves later, Alekhine had blasted open the weakened central files, exposing Steiner’s king and preparing his larger attack. Both his bishop and rook threatened devastating angles on the king. Alekhine went on to win the game.

More than a century later, the Alekhine defence is one of the most popular responses to 1.e4. In a popular variation, the Black player will happily dance their knight around the board and draw their opponent’s pawns out of position.

The key logic is to fool your opponent into thinking they have a great opportunity. They feel like they’ve built a centralized wall of pawns, but they’re out there all alone. They’re vulnerable. Black can attack them whenever he wants, and now White is forced to defend an over-extended structure. White is playing on Black’s terms.

That same logic is a central pillar of Brian Flores’s defense. His exotic scheme has proven elusive to understand outside of nominal statistics like a high blitz percentage and elite production. Minnesota’s top-3 defense by EPA/Play has held several teams to one or zero touchdowns and won games with several offensive turnovers.

You probably understand a few of the main principles of Brian Flores as a defensive coordinator. I’m guessing you know that he likes to blitz a lot. Perhaps you know that he prefers split-safety coverages or that he has the abrasive style typical of a defensive coach.

I’m here to flesh that knowledge out. By the end of this two-part series, you will understand the high-level principles and the individual-level tools that make Flores’s defense sing. You’ll understand the kinds of players he needs at each position and the way he repaired the weaknesses that undid him in 2023.

Who We Got Out There?

Before the defense even breaks their huddle, things can look a bit weird. There are three safeties on the field? And just one linebacker? And this is a running down?

I could list a bunch of personnel groupings at you, but that would quickly turn unintelligible, so let’s think about this in systems instead. Defensive personnel has to respond to offensive personnel. If your big guys are out there, my big guys are out there. Buck this trend if you’re so bold, but for the most part, Base offensive personnel gets Base defensive personnel.

For Flores, “Base” means three true defensive linemen (think Harrison Phillips) and four linebackers - two outside (Andrew Van Ginkel) and two inside (Blake Cashman). I prefer to think of Van Ginkel types as defensive linemen since their main job is to pass rush, but that’s just semantics.

That leaves four defensive backs, probably two corners and two safeties. Normal stuff any Madden player is familiar with.

Against lighter personnel, like the 11 personnel looks that dominate almost every offense in the league, Flores will remove one of the defensive linemen and replace him with a defensive back. That’s 4-2-5 nickel, and we’re on pretty standard ground for 21st-century 3-4 defenses.

But which defensive back? This is where we start to veer into the wilderness. You probably think the default answer is a nickel cornerback, probably smaller, suited to the slot. Your Captain Munnerlyn types.

Flores will do that, kicking Byron Murphy inside and running Shaq Griffen out there to play with Stephon Gilmore on the outside. But he also likes a third safety - call that “Big” nickel. That’s the Josh Metellus role.

Why not both? With Blake Cashman out earlier in the season, Flores leaned on his “Dime” package with six defensive backs. Three corners, three safeties, four linemen, one Ivan Pace. That’s a 4-1-6 package.

Every “nickel” package, whether it’s the standard 4-2-5 or a 5-1-5 with Van Ginkel, Greenard and Dallas Turner out there has a “Big” variant. Replace Shaq Griffin with Joshua Metellus whenever you want.

The defensive line packages have non-standard variants as well. On 3rd downs, the Vikings love to put four outside linebackers on the line and play a normal secondary structure behind it, whether standard nickel or big. Call that a “Light” variant, which is a name I had to make up because I don’t have access to their real internal dialogue. That’s going to happen a lot, we’ll get through it together.

Add this to your bog standard goal line (call it “Heavy”) and long yardage packages, and you get a wonderfully varied menu of personnel options. We can say something like “Light Big Nickel” and know that means four edges on the line, two linebackers, two corners and three safeties. We’re building a system of communication here.

This is already hard to plan for. Who do you scout? Whose weaknesses do you try to exploit? Will they even be on the field? Logistically, it means a lot of rotation. 15 Vikings players have played more than 33% of available defensive snaps.

Patrick Jones II and Jihad Ward are more than backups, they’re 3rd down specialists, mismatch hunters on the interior, and goal line specialists. They keep the starters fresh. Deep roster underdogs like Jalen Redmond can come in fresh, flash for a few plays then rotate back out.

So we know who is out there. Now we have to get them aligned.