The Super Bowl Parade Shooting: Guns and the Inevitability of Violence

Americans cannot avoid mass shootings, even in their most "depoliticized" moments. The shooting at Union Station in Kansas City demands we look at guns, gun culture, legal fictions and violence itself

On the sixth anniversary of the Parkland School Shooting, Valentine’s Day, gunmen perpetrated another mass shooting at the Super Bowl parade held to celebrate the Kansas City Chiefs win over the San Francisco 49ers just a few days prior.

It is not quite a coincidence that the parade shooting occurred on the same day as another massacre; in 2021 there were 686 mass shooting incidents, just a bit more than the 636 in 2022, according to the research produced by Everytown, an anti-gun violence advocacy group.

With more than one mass shooting incident a day, it’s an almost necessary condition that one occurs during the anniversary of a more significant and well-known one.

The statistics, of course, are in dispute — there is no agreed-upon definition of a mass shooting, so various counting methods will produce various results. The image that the phrase “mass shooting” evokes is not in line with many of the broader definitions. The Violence Project uses a much narrower definition, culled from the Congressional Research Service.

The Congressional Research Service has defined a public mass shooting as a “a multiple homicide incident in which four or more victims are murdered with firearms”, not including the shooter(s), “within one event, and [where] at least some of the murders occurred in a public location or locations in close geographical proximity (e.g., a workplace, school, restaurant, or other public settings), and the murders are not attributable to any other underlying criminal activity or commonplace circumstance (armed robbery, criminal competition, insurance fraud, argument, or romantic triangle)

This aligns with our image but excludes a number of public shooting events where multiple people die. Using this definition, the “number” of mass shootings drops dramatically, instead of 600-plus events over a single year, there are about 193 over 60-plus years.

What this doesn’t change, however, is the number of shooting deaths there are every year.

We have used mass shootings as our proxy for talking about gun violence. Most gun violence occurs in the background of our understanding — suicides exceed homicides in firearm-related deaths in every year of data that we have, and deaths from homicides from non-mass shooting events far exceed those from mass shooting events.

Tragic events like those in Kansas City — where at least 21 people have been injured, with one dead — are a harsh reminder of this uniquely American problem while operating outside of the scope of what this problem often is.

Guns Mean Gun Deaths

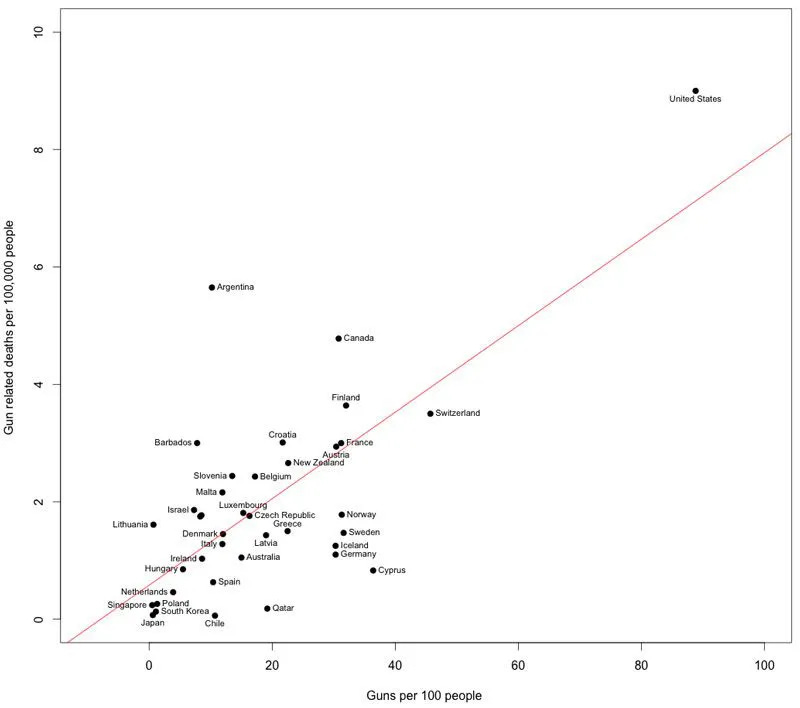

There is inarguably a connection to gun prevalence in the United States and gun deaths. When comparing gun deaths to gun ownership one sees a linear relationship across countries. The relationship holds at the state level, too.

A meta-analysis consisting of 130 studies encompassing the gamut of countries and states that have enacted restrictions on access to guns have overwhelmingly found that gun deaths decrease as laws are passed reducing access to guns and that gun deaths increase when laws are passed enabling ownership or exculpating owners from using firearms (like “stand your ground” laws).

The analysis also found that overall deaths, including suicides, decreased in countries that passed restrictive firearms laws, suggesting that the substitution effect is small. This impact, especially when it comes to suicides, is extremely well-established in the literature.

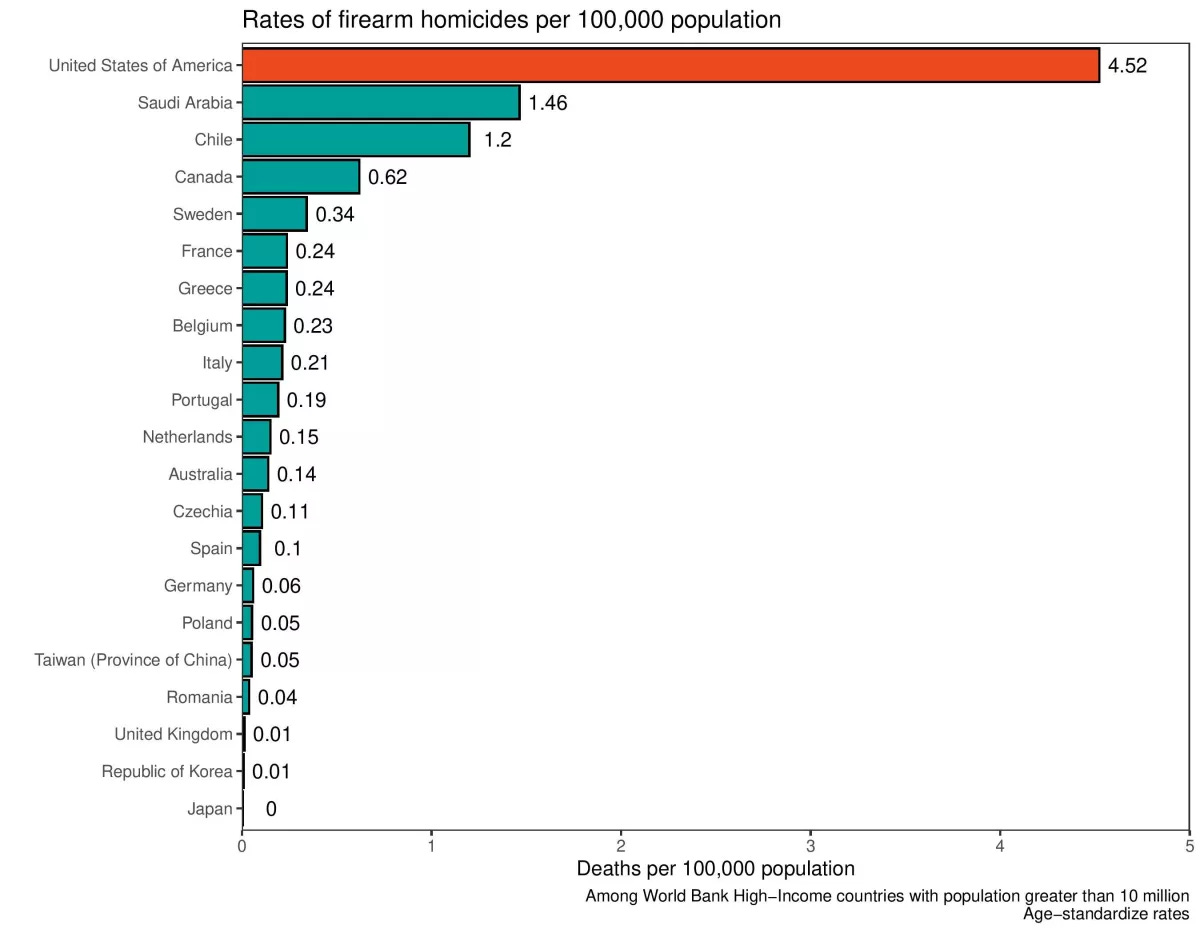

A relatively small substitution effect has been consistent with the data for a long time; as a University of San Francisco study pointed out, “In 2010, the US homicide rate was 7.0 times higher than the other high-income countries, driven by a gun homicide rate that was 25.2 times higher.”

The fact that these relationships hold at the state level despite the relative ease of crossing borders to take advantage of laxer gun laws in another state is fairly astounding. The same effect has been found in other countries with federalist structures — stricter gun access laws in individual states or provinces generally result in fewer deaths despite ease of travel across borders.

Relatively high ownership rates do not deter gun deaths or mass shootings, regardless of the definition. They do not inhibit the number of deaths — quite the opposite, as gun ownership rates predict the likelihood of mass shootings in both frequency and severity.

We also know this holds true for partial measures — restrictions on “assault weapons” and high-capacity magazines reduced gun deaths in mass shootings, while the expiration of such legislation saw a spike in mass shooting fatality.

The pushback on this has been two-fold: good samaritan arguments unsupported by the data and Constitutional claims.

The Constitutional Argument is Flimsy

In the strictest legal sense, the Constitutional argument is accurate. The Supreme Court has ruled that the Constitution recognizes an individual right to bear arms. That ruling was surprisingly recent, coming in 2008 in United States v. Heller.

There is no long-running legal tradition of the courts recognizing an individual right to firearms and originalists and textualists — often legal philosophies associated with conservatives and Republicans — would be hard-pressed to find arguments defending this interpretation.

The belief that this is a part of a long-standing American legal history is a fiction, as Politico pointed out in a piece in 2014. Neither the text of the Second Amendment nor the Founder’s intent gives us that interpretation — and neither do court rulings between the 1770s and the 1930s.

There is not a single word about an individual’s right to a gun for self-defense or recreation in Madison’s notes from the Constitutional Convention. Nor was it mentioned, with a few scattered exceptions, in the records of the ratification debates in the states. Nor did the U.S. House of Representatives discuss the topic as it marked up the Bill of Rights. In fact, the original version passed by the House included a conscientious objector provision. “A well regulated militia,” it explained, “composed of the body of the people, being the best security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed, but no one religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person.”

Though state militias eventually dissolved, for two centuries we had guns (plenty!) and we had gun laws in towns and states, governing everything from where gunpowder could be stored to who could carry a weapon—and courts overwhelmingly upheld these restrictions. Gun rights and gun control were seen as going hand in hand. Four times between 1876 and 1939, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to rule that the Second Amendment protected individual gun ownership outside the context of a militia. As the Tennessee Supreme Court put it in 1840, “A man in the pursuit of deer, elk, and buffaloes might carry his rifle every day for forty years, and yet it would never be said of him that he had borne arms; much less could it be said that a private citizen bears arms because he has a dirk or pistol concealed under his clothes, or a spear in a cane.”

Legal tradition at the time included the norm that officers arrest those openly carrying arms. Courts in the early period of American history would explicitly deny the individual right to bear arms because police officers fulfilled that function.

Massachusetts was not alone in its broad regulation of public carry. Over the next several decades, Wisconsin, Maine, Michigan, Virginia, Minnesota, Oregon, and Pennsylvania passed laws modeled on the 1836 Massachusetts statute. While modern regulatory schemes, such as the “good cause” permitting policy at issue in Peruta, do not operate in exactly the same manner as these regulations passed primarily outside the South in the nineteenth century, they are a logical analogue given present-day circumstances. Significantly, both regimes presume that the state’s police power justifies limiting the right to carry arms in public to circumstances in which there is a clear justification, such as a heightened need for self-defense.

The exception in the South permitted open carry (but not concealed carry) for the explicit purpose of putting down slave rebellions — a dicey legal tradition to draw upon.

It is nevertheless, the only counterargument often used by gun rights advocates; that the non-binding errata of a decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford implies the recognized right of gun ownership — e.g. whether the recognition of Scott as a citizen would imbue him with a body of rights, including the right “to keep and carry arms wherever they went.”

This reading is initially compelling because Chief Justice Roger Taney is listing a number of constitutionally protected rights, like free speech, along with that mention of arms. But it doesn’t hold up, because Taney is making the argument that slaves cannot be part of militias, and therefore would not be able to bear arms — that is not the reading held in Heller.

It is also unusual to cite what scholars call “fleeting dicta” as part of a long-standing legal argument when a wealth of legal evidence flows the other direction.

Indeed, in 1875, the Court ruled in United States v. Cruikshank that states had significant leeway in restricting access to firearms to citizens.

A big part of the change in our understanding of the Second Amendment comes from a radical change in what the National Rifle Association was intended to accomplish — a product of what was known as the Revolt in Cincinnati.

Originally, the organization was designed to promote marksmanship training and advocate for gun control, as Alternet pointed out. In fact, they helped write most of the federal legislation inhibiting gun use until the late 1970s.

But an internal political takeover in 1977 changed things. As the Washington Post details:

In gun lore it’s known as the Revolt at Cincinnati. On May 21, 1977, and into the morning of May 22, a rump caucus of gun rights radicals took over the annual meeting of the National Rifle Association.

The rebels wore orange-blaze hunting caps. They spoke on walkie-talkies as they worked the floor of the sweltering convention hall. They suspected that the NRA leaders had turned off the air-conditioning in hopes that the rabble-rousers would lose enthusiasm.

The Old Guard was caught by surprise. The NRA officers sat up front, on a dais, observing their demise. The organization, about a century old already, was thoroughly mainstream and bipartisan, focusing on hunting, conservation and marksmanship. It taught Boy Scouts how to shoot safely. But the world had changed, and everything was more political now. The rebels saw the NRA leaders as elites who lacked the heart and conviction to fight against gun-control legislation.

Shortly thereafter, a swath of new Second Amendment-focused articles were written in the American Rifleman, “rewriting American history,” as Alternet wrote.

This invented history has defined much of our understanding of what the Second Amendment means, but it’s also not that relevant — the Constitution is a living document. It has been changed dozens of times. If there is political will to change it in order to save American lives, it will be changed.

But that’s not happening, in part because of the importance of guns in American culture.

Gun Culture is Real, Built On A Fiction

American gun culture is not a product of paranoid gun owners overly concerned about hero narratives or home intrusion scenarios. While most gun owners will provide self-defense as a reason for ownership, the culture it emerges from is a complex, many-layered phenomenon built from social strands that are in some ways uniquely American and in other ways invented.

But culturally, guns aren't just a reaction to anxieties. In a way gun control advocates rarely consider, but gun owners may find obvious, they're a meaningful social asset for their owners. In a fragmented society, guns connect people at a time when making connections is ever more difficult.

In part because of their danger and allure and in part because they're the center of a sporting culture with deep American roots, guns draw adherents together in contexts like expos, gun ranges, and online chatrooms. At the recreational level, participants can indulge in hobbyist debate and discussion; on a political and cultural level, they can also forge a shared commitment to armed citizenship.

Gun owners bond over their shared fear of diffuse and unpredictable threats of contemporary life. The Pew survey concluded: “Many, but not all, gun owners exist in a social context where gun ownership is the norm. Roughly half of all gun owners say that all or most of their friends own guns. … In stark contrast, among the non-gun owning public, only one-in-ten say all or most of their friends own guns.”

Those social connections help organize gun owners' lives and make them meaningful. Seen in this light, as sociologist David Yamane puts it, “Guns are normal and normal people use guns.”

Guns are a hobby that, when treated responsibly, are supposed to imbue a sense of responsibility and reverence for life. Gun ownership can represent a rite of passage and is symbolically much more than a hunting instrument or a method of self-defense.

That said, gun culture emerges from a false historical narrative — one built on an understanding of the American frontier that plays more like a movie than a historical narrative.

The movie requires that colonization be thought of as “progress” and that violence on the “American frontier” was necessary and good. Once that vision of progress has been normalized and established, it provides the foundation for the American mythos built on rugged individualism — one that required a gun.

That is not to say that American gun ownership was itself a historical myth; American citizens owned guns at much higher rates than Europeans for reasons outside of explicit extermination or colonization as well — a society where a larger share of citizens were hunters, for example.

Even on the frontier, however, gun ownership was highly restricted and regulated. Famous frontier towns like Tombstone had much more restrictive gun ownership and carrying laws than almost any American municipality has today. In fact, carrying a firearm in town — concealed or otherwise — was completely prohibited in most frontier towns.

Even though relative ownership rates were high, absolute ownership rates were low. While gun ownership rates are difficult to concretely nail down before the 1970s, the evidence tells us that very few people owned guns prior to the 1850s. In the center of American gun manufacturing, Massachusetts and Connecticut, fewer than 11 percent of citizens owned a firearm.

There’s a lot that connects modern gun culture to slavery. But more important than its connection to the slave trade is how important guns were to maintaining slavery. While we’ve discussed the legal precedent, it’s also important to discuss the cultural impact it had, which the Atlantic does well. Slave patrols play a big part in modern gun culture and hunting is a relatively recent phenomenon with regards to how guns are treated as cultural objects.

While it’s true that hunting has spun off into its own culture, the threads are still there. Slave hunting was a popular activity, and bloodhounds were raised to hunt slaves. Most importantly, modern gun culture has much more to do with latent racist fears than it does with hunting. What’s amazing is that hunting culture is in part a product of corporate marketing.

In order to sell his revolver, Samuel Colt had to propagate a myth of American frontiersmen and high crime rates, despite the fact that crime was so low that police were unarmed throughout the North. In the South, police were armed for the purpose of fighting a war against rebelling slaves.

That doesn’t make modern American gun culture fictional, or those who enjoy guns and the culture surrounding them inherently racist. The social bonds developed through this culture are very much real and need to be a part of the conversation — but they are built on a sensationalized and racist understanding of American history. That has to be reckoned with, too.

Are Guns “The Problem”?

It is dispositively the case that the presence of guns accelerates and exacerbates violent situations in deadly ways. It is also very clear, based on the evidence, that restrictions on the ownership of guns reduce the deadliness and frequency of violence.

From a policy standpoint, that might be enough. But identifying an accelerant — the gasoline poured all over the country — doesn’t get us closer to finding the match.

It is entirely understandable why some roll their eyes when they hear “guns don’t kill people, people do,” because it is an overly reductive aphorism that doesn’t suggest a solution and often denies the magnitude of the problem.

But the core of it does speak to something real; the drive to engage in violence in the first place. Earlier in the piece, there’s a chart that isolates the United States as unique in its capacity to produce gun violence among its peers.

This only holds for countries with a relatively high level of income. The effect disappears when including a variety of countries.

Not only that, the European countries that are closest to the United States in gun ownership rates, like Finland, Sweden and Switzerland, are several times safer in terms of firearm homicide rates (but not suicide rates).

Some of that has to do with the nature of gun ownership in those countries — they are often long rifles rather than handguns and the ownership rates emerge from the mandatory service that those countries require of their male adult citizens.

It is also hardly surprising to see that firearm deaths are higher in countries with social unrest and economic inequality. The drive to commit violence is part of the issue as well.

I touched on how we define violence in a previous piece discussing Israel and Palestine. In short, it is much more than the act of pulling a trigger; it also includes creating systems that hasten or ensure death. The response to those systems can be explosive.

The revulsion from the left to right-wingers who argue that the issue isn’t guns, it’s “mental health” is justified; the United States is not alone in having mental health issues and those same conservatives often eliminate funding for mental health care. It’s a disingenuous canard that plays on the inability to understand why someone would commit violence rather than genuinely exploring the causes of violence.

But systems that would create better mental health would reduce violence; not because people with mental health concerns are violent — they are more often the victims of violence than the perpetrators. Rather, tackling one helps tackle the other. That doesn’t just mean funding mental health care but reducing stressors that contribute to mental illness — access to food, shelter, water and medicine.

Crime is a sociological phenomenon motivated primarily by economic factors; crime on a global and local scale tracks with economic factors; the need for internal violent governing structure because of an abandoned community creates gangs while the need for security drives robbery and theft.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t ideological factors at play or that crime is exclusively economic. Sexual violence stems from deeply rooted gender dynamics, sexual ownership, power and more.

Though the argument that guns aren’t the problem comes from a place of bad faith from political pundits, it’s well worth examination. In the meantime, we should clean up the accelerant while we find the match.

Really well written article, thank you, Arif. This serves as a pretty definitive evaluation of US gun violence and a great place to start a conversation on how to fix it.