The Brian Flores Defense: A Comprehensive Guide, Part 2

Luke Braun completes his two-part almanac on the Brian Flores defense, this time going over the intricacies of coverage and blitz design.

[Ed. Note: This is part 2 of a series describing Brian Flores’s defense and its principles. Here’s part 1, which also explains the chess shit you’re about to read.]

In the 1972 World Chess Championship against Boris Spassky, Bobby Fischer stunned the world by playing the Alekhine Defence.

Fischer had the chance to take the crown from the Soviet Union for the first time in 24 years. He was also outmatched. He had never defeated Boris Spassky in any meeting prior. But he played well for the first 12 games, earning a two-game lead. In game 13, with the Black pieces, he chose to play the Alekhine.

Fifty years after Alexander Alekhine popularized the idea, it had been completely figured out. It still sees use at the highest level today, but only as an exotic niche that grandmasters hope their opponents haven’t studied as much.

You’ll remember from the last piece that the Alekhine Defence is mainly designed to get White to overextend their center and create vulnerabilities. Beyond the tactical idea, it’s meant to make White uncomfortable. It’s unfamiliar.

People make mistakes when they’re uncomfortable. Even those at the top of their position can be coaxed into a regrettable decision. In this case, Spassky’s decision was Knight to d2.

Sure, the Knight now defends both the Bishop on b3 and the other Knight. But neither of those pieces are under attack. It’s passive. It’s conservative. Because Spassky didn’t know what attack was coming, he didn’t know how to set up for it.

These days, grandmasters prefer to move their Queens out to e2, giving it access to more squares while still supporting that vulnerable center. But Spassky blocked his Queen off. In his next move, still unsure, he shyly moved a pawn on the edge of the board.

That’s all the time Fischer needed to launch his ultimately deadly attack. It’s not that Spassky’s move worsened his position. It was a perfectly sound defensive setup. Just passive.

Fischer launched a pawn forward on the other side of the board, and Spassky couldn’t slow it down. He hadn’t set up for that. All he could do was launch his own pawn forward, leaving it vulnerable to attack.

Spassky was taken completely out of his element. The fall of the a4 pawn set Fischer up with the upper hand. The game went down as one of the most exciting and interesting chess games of all time, with Fischer in the driver’s seat throughout the match. Spassky ultimately resigned after 74 mentally grueling moves.

A computer would never lose this game. Computers don’t have the kinds of emotions that humans do. They don’t adhere to vague principles. Humans are vulnerable to confusion, to panic, even at the highest level of their craft. Whether it’s chess or football, make your opponent panic and good things will happen.

Even if they can beat you once or twice, over the course of a game, that chaos builds. Mistakes get made. Structures fall apart. You just have to keep on the pressure.

"I like the moment I crush a man's ego."

~Bobby Fischer

In this piece:

How Flores Organizes His Blitz

In the last entry, we learned how Flores sets up his fronts to maximize chaos pre-snap. These looks confuse run game plans, but also pass protection plans. In fact, Flores’ fronts can force the offense into the protection he wants. And if he knows the protection, he knows exactly how to attack it.

Without going too deep into offensive line structures, the basic rule set relies on which linemen are “covered” and which are “uncovered.” Offenses call their protection to the left or to the right, and then linemen look if there’s a guy to that side. If there is, they’re covered, and if not, they’re uncovered.

If the offense wants to split the protection into two sides, they’ll split it at the first uncovered player. After all, if the line is going to part, it shouldn’t part right in front of a guy.

But this is exploitable. Flores’s pressures often attack an uncovered gap, hoping that a blitzer or stunting pass rusher will find a wide open lane to the quarterback.

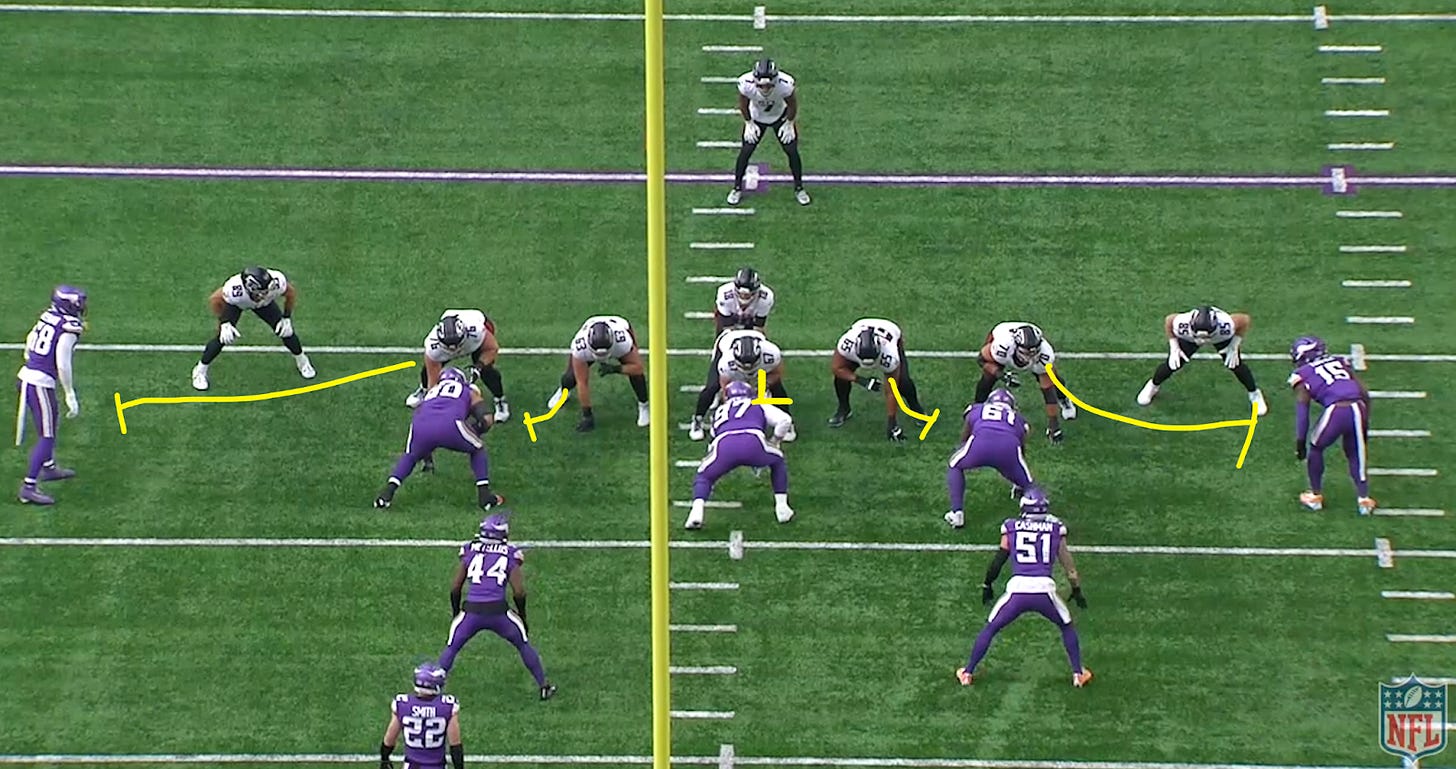

Here, Flores uses his “Cover 0” look to stack up a player on every single blocker, with an overhanging Harrison Smith to boot.

The line has no choice but to slide to its right, splitting away from left tackle Jake Matthews, who will be alone in the octagon with Jonathan Greenard. The running back will have to take Blake Cashman if he blitzes, but he also has to keep an eye on Harrison Smith. He can’t block both.

Kirk Cousins does well to get the ball out before an unblocked Harrison Smith can get to him. But think in opportunities instead of results. Greenard has a clean one-on-one with nobody helping Matthews. Cashman has a one-on-one with the running back. And Harrison Smith has a free run to the quarterback, if only he can get there in time.

Their other fronts put stress on these same rules. Take their 5-0 “Ragnar” front, which guarantees that all five linemen are covered.

That puts every single member of the offensive line in a one-on-one matchup. The only way the offense can help out is to use more skill players, taking them out of the route concept. That’s already a win. Some players have good opportunities and all the coverage jobs just got easier. Before the snap, Flores is forcing the offense to shyly push its pawns forward.

We can make things worse.