The Vikings (Probably) End Their Season: Loss to the Packers Invites Big Questions

The Minnesota Vikings lost in embarrassing fashion to the Green Bay Packers, a game both embedded with meaning and devoid of any new takes.

At 4-7, the Vikings have essentially lost out on their chances at making the playoffs. They aren’t mathematically eliminated — only the Giants are — and there’s still a mathematical path to win the division.

But Minnesota’s 23-6 loss to the Green Bay Packers represents the end of the sliver of hope that the Vikings could turn the season into something immediately meaningful.

In an effort to avoid this, the Vikings seemingly engaged in an overcorrection game; J.J. McCarthy threw it short too often with deep options open downfield and Kevin O’Connell ran the ball more often than he ever had in a first half.

Avoiding Meaningful McCarthy

Until it had become inevitable, the Vikings were insistent on running the ball. Was it the correct call? Probably — the Vikings averaged minus-0.16 EPA per rush attempt and generated a success rate of 32 percent. That might seem low, but on passing attempts, they averaged minus-0.67 EPA per dropback and earned a success rate of only 16 percent.

In simpler terms, the Vikings averaged 2.48 yards per dropback and 4.36 yards per designed rush attempt.

After McCarthy’s first two starts — one of which featured an improbable fourth-quarter comeback — some had been certain that his performances, each worse than minus-0.50 EPA per play, would be the worst he’d ever play in a Vikings uniform.

Against the Packers, McCarthy managed minus-0.67 EPA per play, the worst we’ve seen from him and from any quarterback in a Vikings uniform since Matt Cassel’s 2013 performance against the Cincinnati Bengals in Week 16 of the 2013 season (minus-0.86 EPA per play).

Since 2000, only four quarterback performances have been worse: Christian Ponder in Week 14 of the 2011 season at the Detroit Lions (minus-0.74 EPA per dropback), Spergon Wynn in Week 17 against the Baltimore Ravens in the 2001 season (minus-0.77), Cassel against the Bengals and Brad Johnson in Week 13 of the 2006 season against the Chicago Bears (minus-1.05).

Of the 406 quarterback performances with at least 20 dropbacks the Vikings have had since the 2000 season, McCarthy has only participated in six of them. Yet, he owns three of the 15 worst performances in that span of time.

Last week, we looked at the history of quarterback starts to see what we could learn about small-sample, high-magnitude performances like what we’ve seen from the beginning of McCarthy’s career.

An increasingly statistically literate fanbase has come to understand that we should be wary of small samples, but it should be noted that the number of observations one needs to come to a confident conclusion about a dataset reduces as the magnitude (or effect size) of those observations increase.

The magnitude here is pretty substantial; only one Vikings quarterback with at least 100 dropbacks since 2000 has had worse production: Spergon Wynn (minus-0.37 EPA per play).

This is the 15th-worst career performance since 2000 of any quarterback in the NFL. It is entirely possible that he gets out of this category, of course, because many of these quarterbacks have played for multiple games across multiple seasons while McCarthy is just beginning his career. But it’s not a wonderful start.

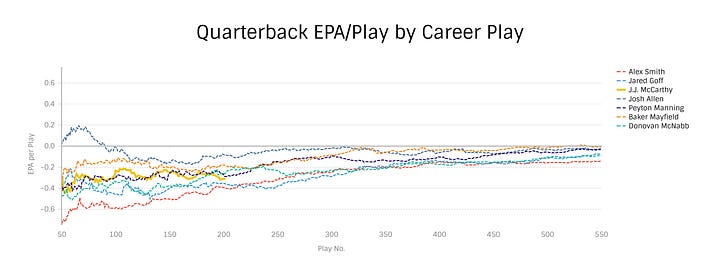

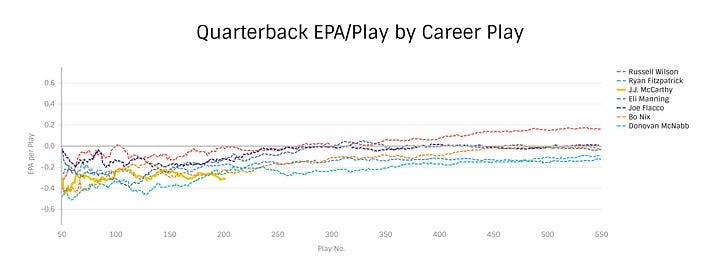

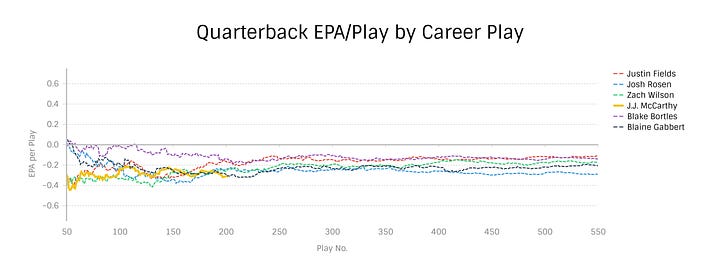

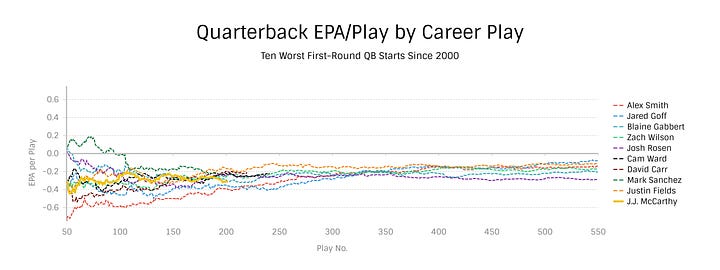

With the “first six starts” caveat in mind, we can update the charts used in last week’s piece to track McCarthy’s progress against other early poor performers.

Added to that gallery are the ten worst starts among first-round quarterbacks.

How much of this has to do with his environment? After all, McCarthy suffers from the worst drop rate in the league, and his receivers did him few favors in last week’s outing against the Chicago Bears.

The rate at which his pocket was under pressure, at least according to Pro Football Focus’ initial accounting, was 44 percent. NextGenStats recorded an even higher pressure rate — 48.0 percent. That’s a 12th percentile outcome, truly abysmal.

But pressure is not just the product of offensive line play. If a quarterback holds on to the ball longer than can be reasonably expected for an offensive lineman to hold up, then the pressure shifts in responsibility from the offensive line to the passer.

But McCarthy’s time to throw was once again slow; at 3.32 seconds, it was his fourth-fastest of the season but still in the 90th percentile of time-to-throw for quarterbacks. Only one player has a longer time-to-throw than McCarthy does this season: Caleb Williams.

Using NextGenStats data, we can parse out all the plays where quick pressure — hurries that appear in 2.5 seconds or fewer — impacted the play, instead focusing on plays with long pressures or those without pressure. In that exercise, McCarthy’s game against the Packers was the second-worst of the season by EPA per play.

And yes, it is the case that even with the fourth-quarter comeback, McCarthy’s performance against the Bears in Week 1 when eliminating quick hurries was abysmal.

This gives greater, absurd, context to a response Kevin O’Connell gave in the postgame presser to a beat reporter who asked whether it was possible to win games with McCarthy playing at this level. He said, “I think you can. I do believe that.”

He added, “But it does require as a football team not doing things that lose games; special teams turnover in two out of our last three games and then ultimately the defense is out there battling, they’re trying to get the ball back for us as much as we can.”

The question was designed to find ways around the quarterback’s play, so it’s not entirely as if O’Connell is going out of his way to blame the other elements of the team. He tried to hedge that in his follow-up while still insulating McCarthy.

“There’s some things where you can’t have breakdowns around that player [in order] to consistently sustain [drives]. As some of those things happen or you start stacking negatives, that becomes incredibly difficult for any quarterback, never mind a guy just still in his single-digit world of career starts,” he said.

“So we’ve got to keep putting together plans that give us a chance to express what we want to be as an offense with some talented players,” he added, “While also giving him a chance to grow, but not putting the game totally in his hands where the variance of a young quarterback will cost our whole team.”

This is essentially untrue. In the last 10 years, there have been 289 games in which one team has generated an EPA of minus-0.50 or worse per dropback. The record of those teams is 22-266-1, or 0.078.

But maybe one of the necessary elements is that the defense holds the opposing quarterback to that standard. If we include every game in the last decade where either team has that abysmal mark or worse, we have a universe of 323 games. In that set, teams are 39-283-1, or 0.122. What a relief.

Evaluating McCarthy

How was McCarthy specifically poor in this game? After all, if we’re meant to track progress, it’s not necessarily production that gives us a clue into his progress, but his traits.